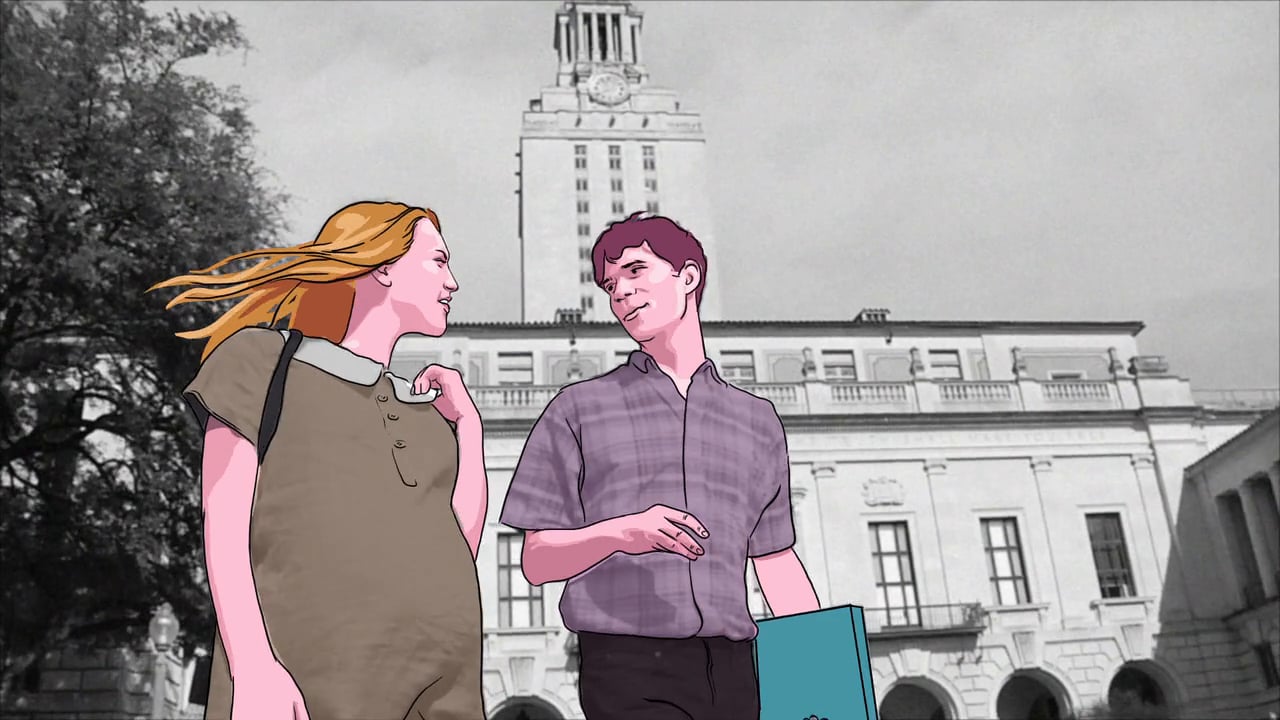

On a blisteringly hot August day in 1966, Charles Whitman — a former Marine who’d killed his wife and mother the night before — climbed the the Main Building tower at the University of Texas with an arsenal of weapons and started shooting. An hour and a half later, 16 people were dead and dozens wounded.

Tower is not about Charles Whitman.

Keith Maitland‘s documentary almost removes him from the frame entirely. Using rotoscoped animation and actors to restage and recontextualize the events of that day, Tower is explicitly about the victims and the people on the ground. It bears witness. It’s an anti-exploitation film, a sort of memory purge born of empathy. Tower‘s effect is jarring, dislocating, and beautiful.

We meet numerous folks with stories to tell, which Tower allows to unfold in more or less real time. Claire is a pregnant student, and one of the first to be shot. Horrifyingly, she is forced to play dead for the entirety of the ordeal, lying on hot concrete next to her dead lover. Rita is one of the few people brave enough to come to her aid, if only to talk her through on the ground.

Maitland jumps between perspectives, as retold by survivors and reenacted by performers, who are themselves animated. In a kind of paradox, the distancing brings us closer. The radio reporter who gets the word out; the cops who finally climb the tower; the unbelievably heroic, kind of nerdy dude who can’t take it anymore and puts himself on the line to pull the fallen to safety. The woman who, to this day, wishes she’d done something, anything.

When I first heard about this film, I, like many others, sighed deeply. Can a mostly animated retelling of a tragedy, one that’s recurred with alarming frequency in the years since, do justice to it? Will it be gross?

When I first heard about this film, I, like many others, sighed deeply. Can a mostly animated retelling of a tragedy, one that’s recurred with alarming frequency in the years since, do justice to it? Will it be gross?

It can, and it is not. Tower surprises at every turn. By refusing the shooter the spotlight, Maitland ends up giving space for grief, guilt, and humanity. It’s one of the most powerful films of the decade.

Quick Links

Sure, Freddy Krueger will never be as scary as he was when you were 10. His later devolution into purely pun-based terror didn’t help matters, emerging eventually as the Catskills Comedian Who Haunts Our Dreams.

But there’s still something fascinating and disturbing about his first appearance. Wes Craven taps into archetypes and bad dreams, and presents to us a child-murdering boogeyman with razors on his fingers. Give it a look and see if you can’t manage to be 10 again.

(Streaming on Netflix)

Unfairly maligned thanks to the glut of reboots and narratively lazy meta-horror, The Last Exorcism turns out to be a singularly frightening bit of horror. The premise — charlatans run up against true evil — isn’t exactly new, but it grabs its found-footage conceit and runs with it. For at least 2/3 of the film, it absolutely works. And let’s be honest: that’s pretty good, all things considered.

(Streaming on Amazon Prime)

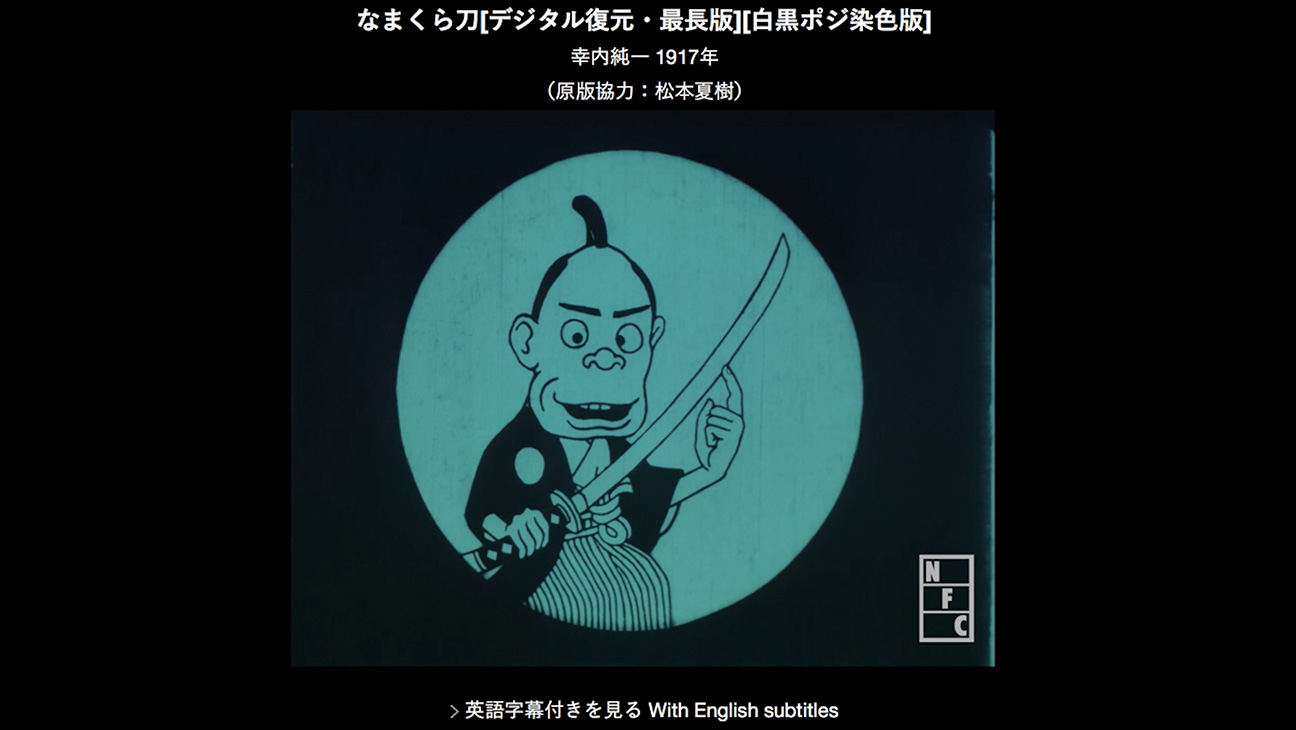

Thanks to the good folks at the University of Tokyo, a wealth of early Japanese film has been made available: fairy tales, pre-war propaganda, and incipient anime, primarily. It’s a treasure trove of movie history.

Recommended: the animated/live-action hybrid The Story of Smoked Weed and The Dull Sword, the oldest surviving entry in the catalog.

(Streaming, courtesy of the University of Tokyo)

A lot of people consider Nightcrawler a bit too “on-the-nose” in its depiction of avarice in the age of mass reproduction, but where would they prefer it punch you? Jake Gyllenhaal is ideally suited for his role as an aspiring crime scene photographer, gleefully deploying the icy artifice that he brings to basically every film. Here, there are no false steps: he’s exactly the guy who would leech onto tragedy for gratifications both public and private. If Freddy Krueger doesn’t haunt your dreams, this dude might.

(Streaming on Netflix)