One of the great joys of the film dork is finding a new What the hell is this? movie, one that they can share with their friends as a baffling experience. There are, however, some fine gradations to the uncategorizable surprise that are sometimes overlooked.

There are What the hell? movies that are really two movies put together, and which switch suddenly switch gears, like Audition; there are What the hell? movies that only seem to have no structure, but which are actually about slowly and inexorably increasing the intensity of the strangeness, giving a firm structure to its structurelessness, like Hausu; and a hundred other varieties.

Of those varieties, none are more boring than a movie with a clever idea and nothing else. Who on Earth is Downsizing for? Who wants a high-concept sci-fi/fantasy comedy/drama from the director of Sideways? Why is Laura Dern in Downsizing for approximately 30 seconds? Why is Downsizing suddenly a white-savior movie? Is Downsizing entirely an excuse for some movie producer with a vore fetish? What is this?

Of those varieties, none are more boring than a movie with a clever idea and nothing else. Who on Earth is Downsizing for? Who wants a high-concept sci-fi/fantasy comedy/drama from the director of Sideways? Why is Laura Dern in Downsizing for approximately 30 seconds? Why is Downsizing suddenly a white-savior movie? Is Downsizing entirely an excuse for some movie producer with a vore fetish? What is this?

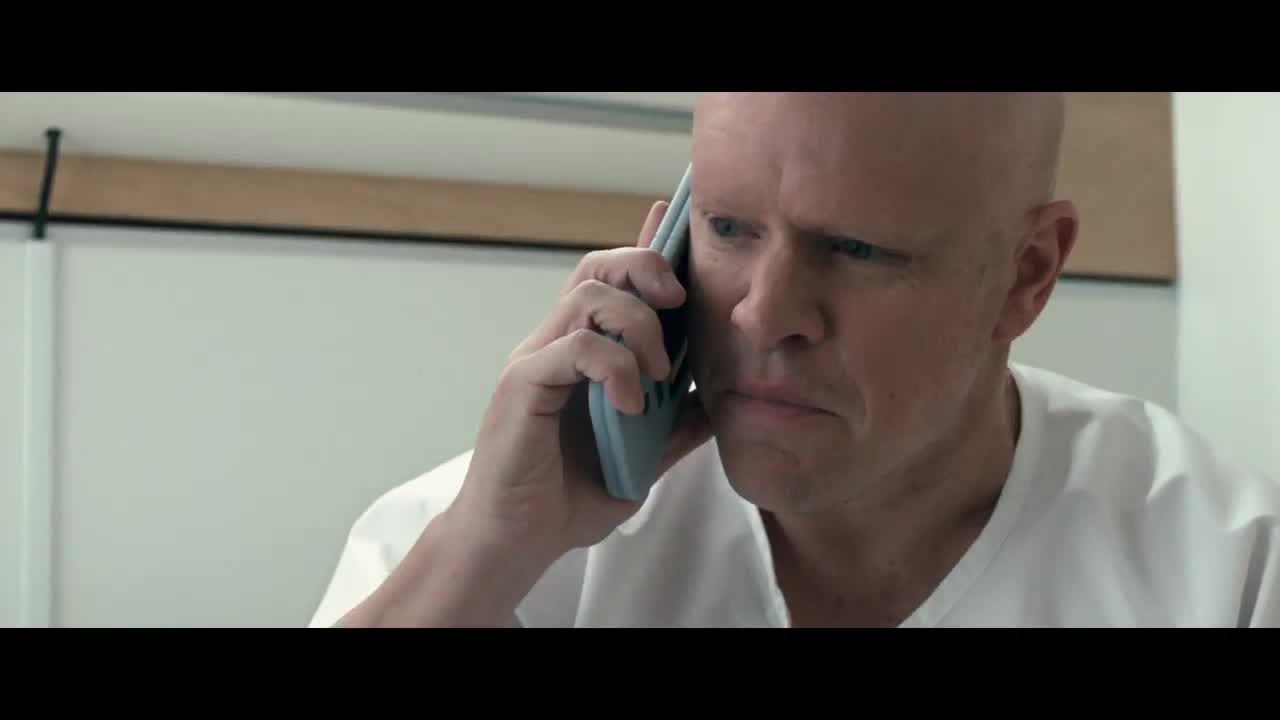

It’s necessary to go through this maze of a script beat-by-beat to accurately communicate its complete senselessness. After the customary “scientific discovery” introduction, we are introduced to Paul Safranek (Matt Damon); we are to infer his life is pathetic from the fact that he is picking up food from a chain restaurant.

He is taking care of his sick mother. And then, suddenly, he’s not; after 4 minutes of nothing, it is suddenly 10 years later, and he, looking identical, is married to Audrey (Kristen Wiig). We’re now given half an hour of awkward, quiet marital strife as they attend a college reunion and shop for houses. They wander around, delivering lines in that moderately-awkward Payne style (a style Matt Damon simply does not have enough charisma to pull off).

It is only at minute 33 that we get to the titular downsizing, by far the most fascinating sequence in the film. For some reason, to be made “little,” you have to have your hair shaved and your teeth removed. So, set to an off-brand Danny Elfman-style tune, Paul is shaved, leaving us the image of a hairless and eyebrowless Matt Damon looking like Guy Pearce at the end of Prometheus.

It is only at minute 33 that we get to the titular downsizing, by far the most fascinating sequence in the film. For some reason, to be made “little,” you have to have your hair shaved and your teeth removed. So, set to an off-brand Danny Elfman-style tune, Paul is shaved, leaving us the image of a hairless and eyebrowless Matt Damon looking like Guy Pearce at the end of Prometheus.

It’s grisly, as we see dentists drill out dozens of patients’ teeth; it’s weirdly poetic in moments, as their hair is shaved off; it is completely, absolutely pointless.

This is the 50-minute mark, and we are almost done with Downsizing‘s preamble. Audrey refuses to get the procedure and divorces Paul, and, through the slow, wandering process by which white middle-aged divorced men fall within the orbit of the kooky non-whites, he ends up neighbors with and attends a party hosted by Dusan (Christoph Waltz, playing a Serbian and speaking in lightly-broken English).

This is the 50-minute mark, and we are almost done with Downsizing‘s preamble. Audrey refuses to get the procedure and divorces Paul, and, through the slow, wandering process by which white middle-aged divorced men fall within the orbit of the kooky non-whites, he ends up neighbors with and attends a party hosted by Dusan (Christoph Waltz, playing a Serbian and speaking in lightly-broken English).

Paul wanders around a party for 15 minutes — at this point, I was half certain I was being pranked — and the real film finally begins. This is actually simply another white savior movie, in which our hero meets Dusan’s housekeeper Ngoc Lan Tran (played by Hong Chau, probably best known for Inherent Vice; here, she speaks entirely in heavily-broken English, which we are supposed to, it seems, find funny).

Past this point, the plot is not worth recapping. Nick purposefully breaks Tran’s prosthetic foot so he can help her take care of those living in the “little” slums. (Is any of the destitution supposed to be some sort of black comedy? In their first scene together, Nick and Tran accidentally overdose a sick friend on Percocet and kill her. Is that supposed to be funny?)

Past this point, the plot is not worth recapping. Nick purposefully breaks Tran’s prosthetic foot so he can help her take care of those living in the “little” slums. (Is any of the destitution supposed to be some sort of black comedy? In their first scene together, Nick and Tran accidentally overdose a sick friend on Percocet and kill her. Is that supposed to be funny?)

As a backdrop to all of this are references to global warming, and the pair end up being offered a position on a Noah’s ark-style attempt to save humanity. They, of course, reject it to continue taking care of the poor and sick, turning the extinction of humanity into little more than an opportunity for a white man to sacrifice himself.

Man Ray famously said that the worst films he had ever watching had 10 minutes worth seeing. Downsizing has at most eight, with the incredible, inexplicable depiction of the process itself. Outside of that, though, it is a useful reminder of a basic rule of film watching: just because something is bizarre doesn’t mean that it’s interesting.