There’s no corner of cinema so explicit about its role as an act of remembrance than documentary film. Any film, in any genre, carries within it an aspect of memory — as a material object that dates from a certain moment and reflects its conditions, and as something more ethereal, something personal, cultural, and collective, subject to revisiting and remapping. Petra Epperlein and Michael Tucker‘s excellent Karl Marx City explores this in fascinating ways.

Part Guy Maddin-indebted excavation of Epperlein’s family and their former lives in East Germany and part true-crime mystery, Karl Marx City is fixated on cinema’s power to document and the ways this power is deployed. The documentary is propelled forward by Epperlein’s quest to find out whether her father, who committed suicide late in life, was a STASI informant, but it’s the film’s complicated grappling with images and their meanings that most resonates.

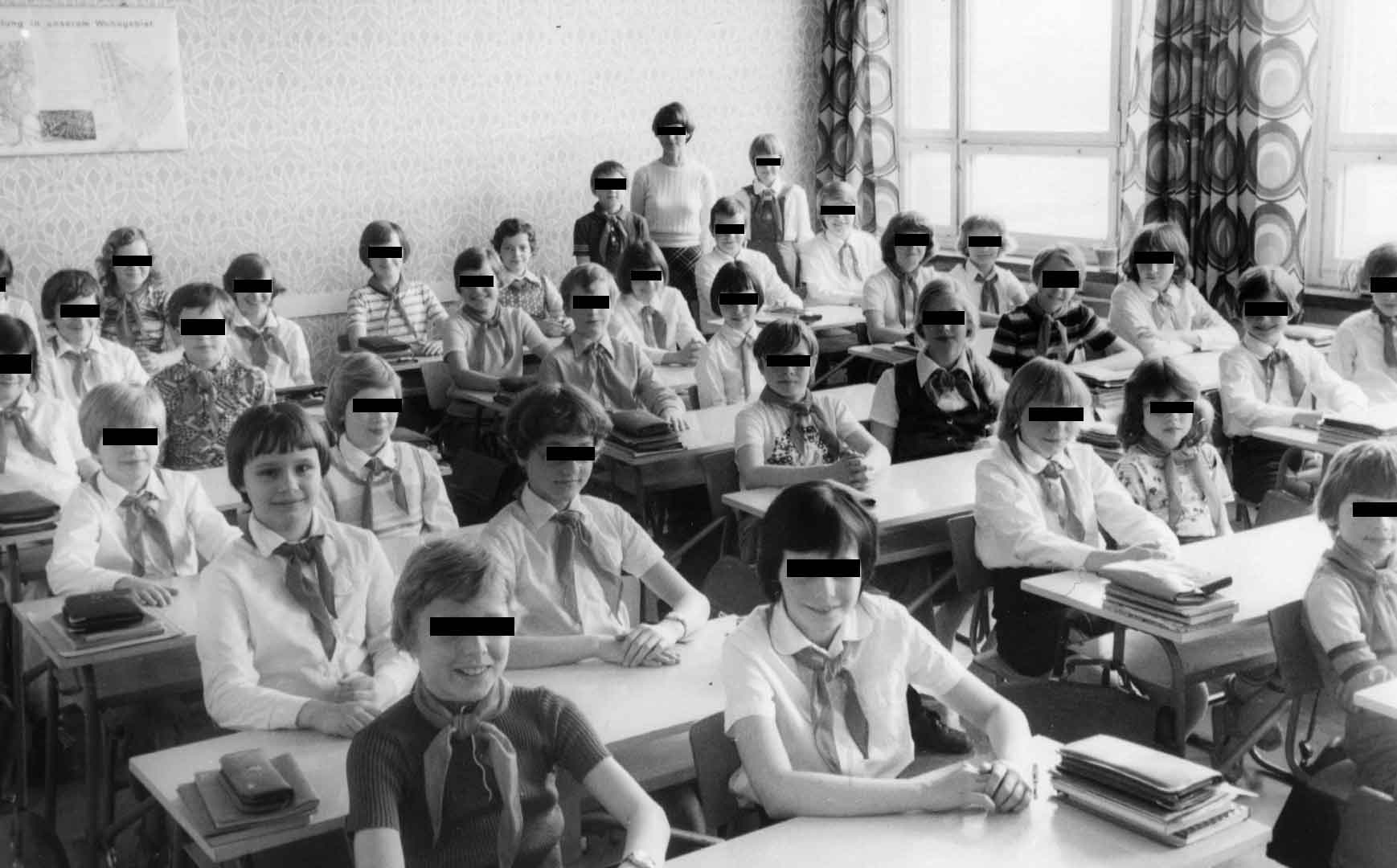

Epperlein, her surviving family, and a crew of experts paint an intimate and unnerving portrait of life in the GDR, famously described as “the most heavily surveilled society in history.” The mundanity of life is emphasized, routines as drab and predictable as the architecture of Karl Marx City (formerly, and currently, Chemnitz), where they live. (At least Epperlein emphasizes this; with some amount of familiar maternal pride, her mom counters that it wasn’t all that bad on the day to day.) At the same time, so is the vast network of informants and cameras, and the looming threat of state pressure.

The evidence of that total control is at the heart of Karl Marx City. Epperlein and Tucker examine not just the sociological implications of constantly being looked at, but their existential consequences, and specifically what it means to have so much of your life documented and reflected back as film. Epperlein’s efforts to uncover the truth about her father are essentially deep dives into an archive; set against the backdrop of the totalitarian state, the act of understanding her own history and the work of the film historian start to blur.

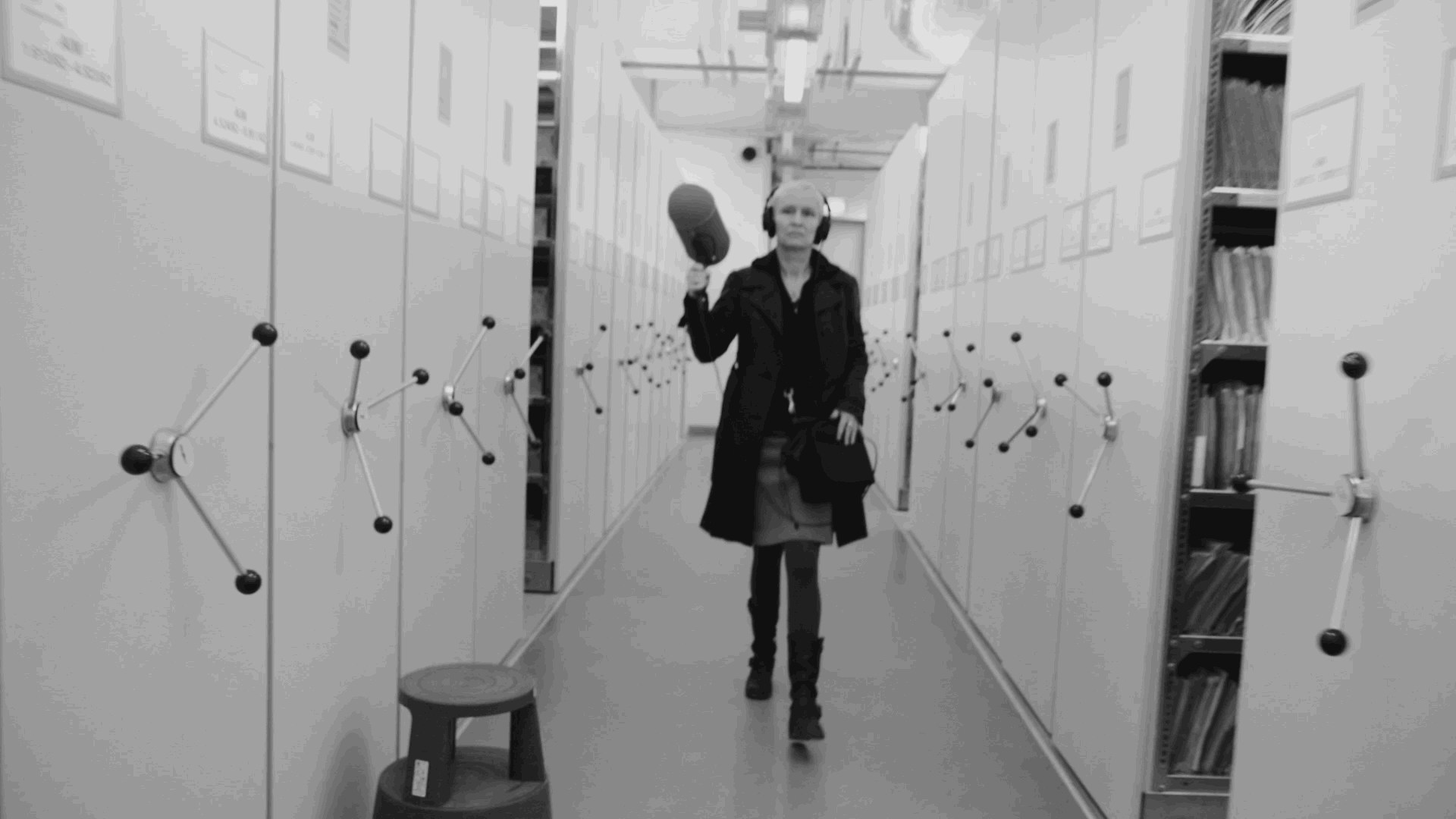

And the work of the filmmaker and viewer, for that matter. Karl Marx City enjoys positing Epperlein as a detective in a film noir. Other times, she’s like a spaghetti western protagonist, marching through the town square or the endless archive with her handheld microphone rather than six-shooter.

In an early sequence, she remembers the East German films they watched, inverse Westerns where the imperialist, capitalist cowboys are shot down by the natives, the U.S. flag set on fire. In Karl Marx City, the image is always up for grabs, and therefore dangerous.

The question of memory’s ownership haunts the film. On some level, the central point is about the ways the state demands a particular kind of forgetting, and wresting back meaning from those would cage it for their purposes. Epperlein and Tucker insert actual STASI recordings into their film, eavesdropping soundscapes from another time echoing into ours, but remixed, reclaimed, redeployed for a voyeurism divorced from its original intent.

The irony, of course, is that the total surveillance of a state structure like the GDR demands total documentation, and documentation enables memory. The fact that the STASI relied so heavily on photo- and video-graphic evidence makes the GDR not just the most heavily surveilled society in history, but, in a weird way, the most cinematic. In the name of total control, the documentarians of the state insisted on creating an imagistic repository of cultural memory that exceeded their grasp.

It’s no accident that, in the wake of the GDR’s fall, citizens stormed STASI headquarters and installations — not, as Epperlein notes, to raze them in revenge, but to seize their own files. If the state’s power was located in their sole possession of information, and the constant threat of disclosure, then one of the first orders of business would be to take it back.

It is a rerouting of narrative on grand and personal scales. As an observer in Karl Marx City notes, the STASI had one story to tell when they collected these images, but he’s not interested in their story. The surreptitiously shot footage, the millions of annotated index cards, the miles of miscellaneous material cataloging every aspect of citizens’ lives end up both revealing and obscuring, creating a vast network of possibilities.

And Karl Marx City ends, as any cinematic interrogation must, with more questions. It, too, can now be located in the archive, for someone else to grapple with.