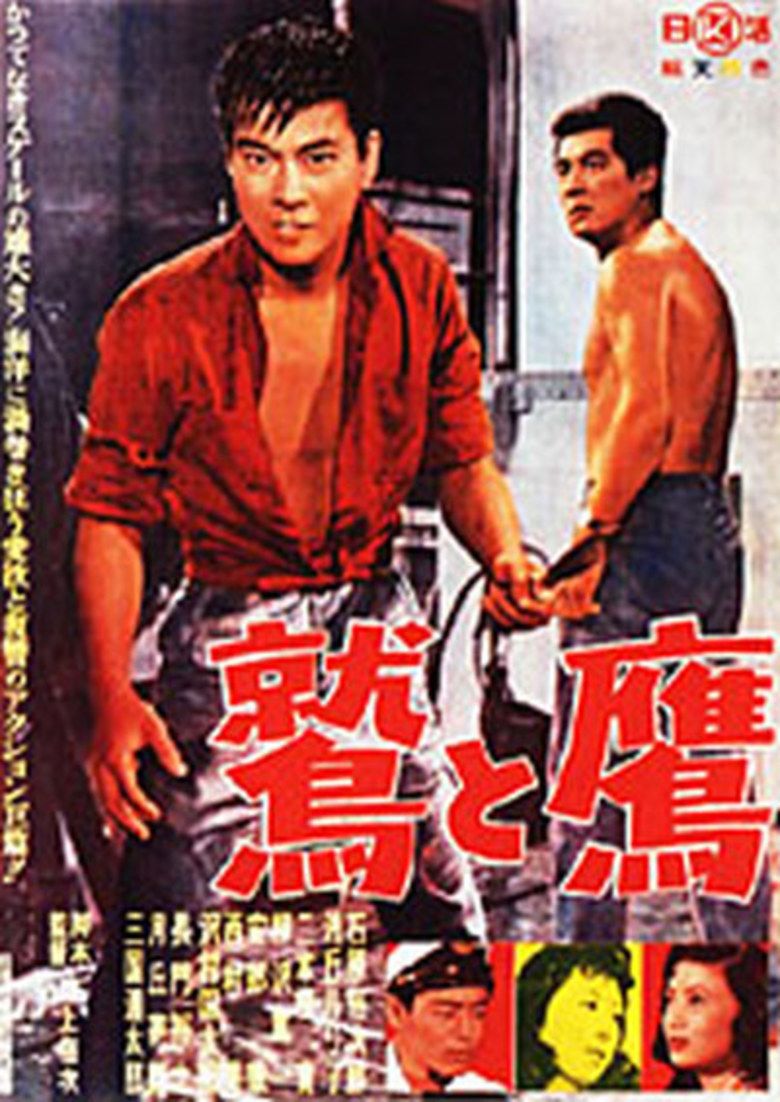

I can’t confirm for sure that the minds behind The Eagle and the Hawk (Washi to Taka, 1957) saw John Ford’s The Long Voyage Home (1940) — a number of shots seem to duplicate ones from the earlier film, although on a ship the number of places from and at which to shoot is certainly delimitable — but I couldn’t stop thinking of the two films next to one another. (In fairness, I saw them at the same theater.)

Both films deal with the standard melodramatic structures of the sea voyage, which literature made unfortunately passé and cultured before film could fully sink its teeth into it. But although they may share certain tropes (the level-headed de facto leader, the booze-soaked party, the secret load of dynamite in the hold), the Japanese film takes every potential seagoing trope to its highest possible level.

The Eagle gives us, recounted in short, two female stowaways (one high culture, one low-class), a love triangle that expands over time into a pentagon, a secret cop, a secret criminal, a dark backstory for the captain and his first mate nephew, a revenge plot, insurance fraud, a climactic typhoon (apparently filmed in a real typhoon), a repeated musical number that becomes plot-relevant, a common-man trope character who wins the lottery while at sea and manages to lose his ticket, and a man-with-a-past one day away from passing the statute of limitations for a long-ago murder.

The Eagle gives us, recounted in short, two female stowaways (one high culture, one low-class), a love triangle that expands over time into a pentagon, a secret cop, a secret criminal, a dark backstory for the captain and his first mate nephew, a revenge plot, insurance fraud, a climactic typhoon (apparently filmed in a real typhoon), a repeated musical number that becomes plot-relevant, a common-man trope character who wins the lottery while at sea and manages to lose his ticket, and a man-with-a-past one day away from passing the statute of limitations for a long-ago murder.

Revealing all of this could be considered a spoiler. But while the epic scope of the melodrama (which manages to fit within a post-Thanksgiving-dinner-stuffed two hours) is certainly based around shocking revelations, they are revelations one hears treading heavily long before they are revealed.

That is, the handsome youngster with a strong right hook (if this film has no point other than getting handsome men to barely wear shirts, it does its job well) will, in fact, be involved with the mysterious murder that opens the film; the shifty captain will ultimately be revealed to be filled with guilt; and the amiable fool who wins the lottery will, in the last half hour, manage to lose his ticket. These beats fall with as little surprise as a tonic chord following a dominant.

But does it matter? Are we so emotionally inexperienced as to need a narrative curtain to keep us present in the scene we are in — that is, to stay present with the deck-set love serenade between ruffian and captain’s daughter that, we know, will not end well? I’m not sure we need such an explicit tool to justify our fantasies.

If The Eagle and the Hawk is unique, it is only in the fullness of its bursting fantasy. But we should not emptily look only for the historically significant and unique fantastic melodrama to justify our interest in an uncomfortably out-of-fashion, rather predictable genre. If there is a film type that helps us learn how to feel — and that is a smaller category than many critics, and fans, accept — it is something like this film.