With several months still to go, and no shortage of forthcoming releases, there’s already been talk about 2018 as The Year of Documentaries. Heather Lenz’s Kusama: Infinity probably won’t top too many year-end lists of these, but it merits inclusion: a solid, empathetic look at an artist whose body of work deserves the attention it’s finally receiving.

Kusama’s relatively recent acclaim was a long time coming. She’s currently most associated with the touring Infinity Mirrors exhibit — like much of her work across media, it’s patterned, recursive, and endlessly hypnotic, with a sense of self-obliteration that ironically seems to mesh perfectly with Instagram sensibilities — but Lenz’s portrait makes clear that there’s more to her art than ready-made selfie opportunities. Like a feature-length retrospective, Kusama: Infinity takes us through an aesthetic magical mystery tour of early watercolors, soft sculpture installations, skewed mirror and light assemblages, pop-art, 60’s nudist happenings, dark collages crafted in a mental hospital, and Kusama’s ubiquitous polka dots. Lenz allows the art to do nearly all of the heavy lifting in the film, the camera panning slowly over the pieces like an appreciative museum-goer. Kusama: Infinity keeps everything at a respectful distance, even when you wish it would probe deeper, but it wears its heart on its sleeve. The film wants to pique your interest in Kusama, and it does.

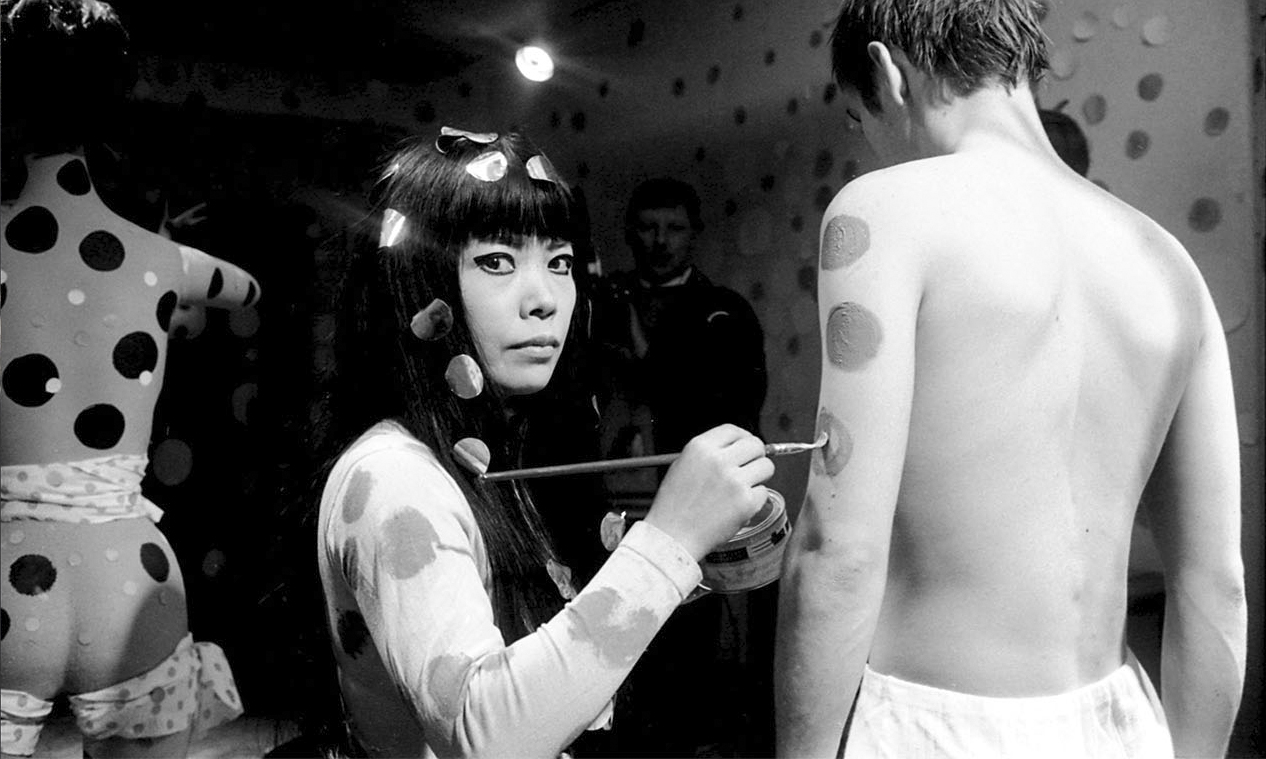

Kusama’s relatively recent acclaim was a long time coming. She’s currently most associated with the touring Infinity Mirrors exhibit — like much of her work across media, it’s patterned, recursive, and endlessly hypnotic, with a sense of self-obliteration that ironically seems to mesh perfectly with Instagram sensibilities — but Lenz’s portrait makes clear that there’s more to her art than ready-made selfie opportunities. Like a feature-length retrospective, Kusama: Infinity takes us through an aesthetic magical mystery tour of early watercolors, soft sculpture installations, skewed mirror and light assemblages, pop-art, 60’s nudist happenings, dark collages crafted in a mental hospital, and Kusama’s ubiquitous polka dots. Lenz allows the art to do nearly all of the heavy lifting in the film, the camera panning slowly over the pieces like an appreciative museum-goer. Kusama: Infinity keeps everything at a respectful distance, even when you wish it would probe deeper, but it wears its heart on its sleeve. The film wants to pique your interest in Kusama, and it does.

Born into a wealthy, unhappy family in rural Japan, Yayoi Kusama wanted to be a painter from the very start, attempting to mount exhibits in the local male-dominated art scene before leaving for the States, with Georgia O’Keefe’s encouragement, to try her hand in a different male-dominated milieu across the Pacific. In America, she faces the double-bind of sexism and exoticist racism; Kusama: Infinity leaves little doubt that, had she been a white guy, it wouldn’t have taken decades to make her name.

Indeed, on multiple occasions, we watch as Kusama’s innovations and experiments are greeted with relative disinterest from the art world, only for their aesthetic repackaging — or outright theft — by Respected Names like Warhol and Oldenburg to be immediately received as masterpieces. Kusama’s spirited forays into nude public art, near-Dadaist spectacle (selling her pre-packaged readymades for $2 outside of the MoMA), and arrestable anti-war interventions, polka dots all around, are described as scandalous, disreputable attention-seeking. The same politically engaged approaches, coming from a male artist, would almost certainly cement a brave legacy of “ballsiness”; instead, they effectively banish Kusama from the public eye, contribute to suicide attempts and worsening mental health.

Lenz’s biographical portrait is affecting both for what it reveals and withholds about its subject, and the film mostly functions as an admiring appeal for wider appreciation, but we’re left with some crucial questions that Kusama: Infinity clearly feels are outside of its scope. We are casually told that an early trauma in a field of flowers led to a sense of being swallowed into the landscape, informing her lifelong fixations, but this thread just trails off. Is it ghoulish to insist on more information from the film on this, if we’re going to talk about it all? Probably, but its inclusion — and Kusama’s own insistence on its centrality to her aesthetic — begs the question. In a sense, it’s very much like David Lynch‘s story in The Art Life, about the neighbor he saw as a child, “Mr. Smith”, wandering at night in some sort of prefigurative Idaho of the mind: “And then Mr. Smith came out … I can’t finish the story.” We’re left with our own worst conclusions, and with the art.

Lenz’s biographical portrait is affecting both for what it reveals and withholds about its subject, and the film mostly functions as an admiring appeal for wider appreciation, but we’re left with some crucial questions that Kusama: Infinity clearly feels are outside of its scope. We are casually told that an early trauma in a field of flowers led to a sense of being swallowed into the landscape, informing her lifelong fixations, but this thread just trails off. Is it ghoulish to insist on more information from the film on this, if we’re going to talk about it all? Probably, but its inclusion — and Kusama’s own insistence on its centrality to her aesthetic — begs the question. In a sense, it’s very much like David Lynch‘s story in The Art Life, about the neighbor he saw as a child, “Mr. Smith”, wandering at night in some sort of prefigurative Idaho of the mind: “And then Mr. Smith came out … I can’t finish the story.” We’re left with our own worst conclusions, and with the art.

The details of the traumas aren’t clear, but the existence of trauma sure is, and through Lenz’s lens we come to understand Kusama’s work as a nearly endless grappling with it. “I come up with new ideas and my canvas cannot keep up with me,” she says, and Kusama: Infinity serves as loving testimony to the braveness of perseverance, despite patriarchy’s best attempts to stifle and obliterate visions it can’t control.

It’s also a remarkable and inspiring picture of one person’s rigorous management of trauma; these days, she keeps a rigorous schedule, dividing her time between the mental hospital where she lives and the studio she and her team have built next door. It’s to the film’s credit that this never seems gloomy or exploitative; that same workmanlike distance, which keeps us at arm’s length narratively, also allows us to simply witness Kusama single-mindedly attending to her affairs in the best ways she can devise, casting wide nets of color that hold things together on canvasses that expand without end. For a life of relentless creativity and equally persistent under-appreciation, it’s as happy an ending as you could hope for.