The latest offering from genre auteur Jaume Collet-Serra and his hangdog, improbably athletic muse Liam Neeson may not be a great work of art, but, like its predecessors Non-Stop and Unknown, it’s compulsively watchable, even fascinating, and guided by a directorial sense that seems excessive for the material. (To say nothing of the Neeson-less The Shallows, which found a way to make a 200-yard swim a marvel of compact storytelling.) Plus, however absurd its narrative resolution, The Commuter also has the added benefit of not turning out to hinge on GMO corn politics, always a good thing.

Like those earlier Collet-Serra/Neeson collaborations, The Commuter focuses on a blank slate of a working man, beset on all sides by a conspiracy that’s singled him out for specific reasons. (Yes, we are asked to believe that our commuter is a paragon of the beleaguered American working man, despite possessing cat-like reflexes, a certain set of skills, and rising 10 feet tall even when stooping, but bear with me.)

Here, Neeson is a former cop who’s given up that dangerous line of work (police work in the movies is, by definition, dangerous) for the almost too on-the-nose banal safety of selling life insurance. Interestingly, we only see Neeson try to sell life insurance once, and he doesn’t seem great at it, and then he gets fired, so perhaps that career move wasn’t so wise after all.

Here, Neeson is a former cop who’s given up that dangerous line of work (police work in the movies is, by definition, dangerous) for the almost too on-the-nose banal safety of selling life insurance. Interestingly, we only see Neeson try to sell life insurance once, and he doesn’t seem great at it, and then he gets fired, so perhaps that career move wasn’t so wise after all.

In The Commuter‘s opening moments, Collet-Serra gives us a cross-faded montage of Neeson’s mornings: a radio alarm clock tuned to news that no life insurance salesman needs, coffee, friendly chats with his college-bound son, a ride to the train from his wife. Shades open up in the narrative: we witness something like contentment bleeding into frustrated boredom, with financial problems on the horizon and quiet apologies contrasted with years-earlier marital bliss. His life seems a ghostly routine, with hints dropped that a break is due.

That break comes first in the mundane form of his lay-off, and then in more pointed fashion on his ride home after a few drinks at the bar. The lay-off itself signals that The Commuter is up to something different than, say, the invulnerable, queasy patriarchy of the Taken series: Neeson is outmoded the demands of the contemporary American workplace, vulnerable precisely because he’s played by the rules. (His much younger boss calls him “a good soldier” and laments that capitalism has no place anymore for his version of nobility.)

When he meets the mysterious, God-like “Joanna” (Vera Farmiga) on the ride back and she offers him a cool $100K, “hypothetically,” to find the person on the train who “does not belong,” it seems both a dubious answer to his financial woes and the kind of plot device that compels us to look closer. In an overt retread of The Box, all he has to do is choose whether to play or not; something will befall a stranger, and then it will be over. When he discovers that this is not a hypothetical, that his family is in jeopardy if he doesn’t comply with these imperatives mysteriously issued from on high, we remember we are in a Liam Neeson movie. He may be a swatted-down victim of the times, but he’s also both cop and actuary, skills he will need to deploy to save any number of lives on the train and at home.

“hypothetically,” to find the person on the train who “does not belong,” it seems both a dubious answer to his financial woes and the kind of plot device that compels us to look closer. In an overt retread of The Box, all he has to do is choose whether to play or not; something will befall a stranger, and then it will be over. When he discovers that this is not a hypothetical, that his family is in jeopardy if he doesn’t comply with these imperatives mysteriously issued from on high, we remember we are in a Liam Neeson movie. He may be a swatted-down victim of the times, but he’s also both cop and actuary, skills he will need to deploy to save any number of lives on the train and at home.

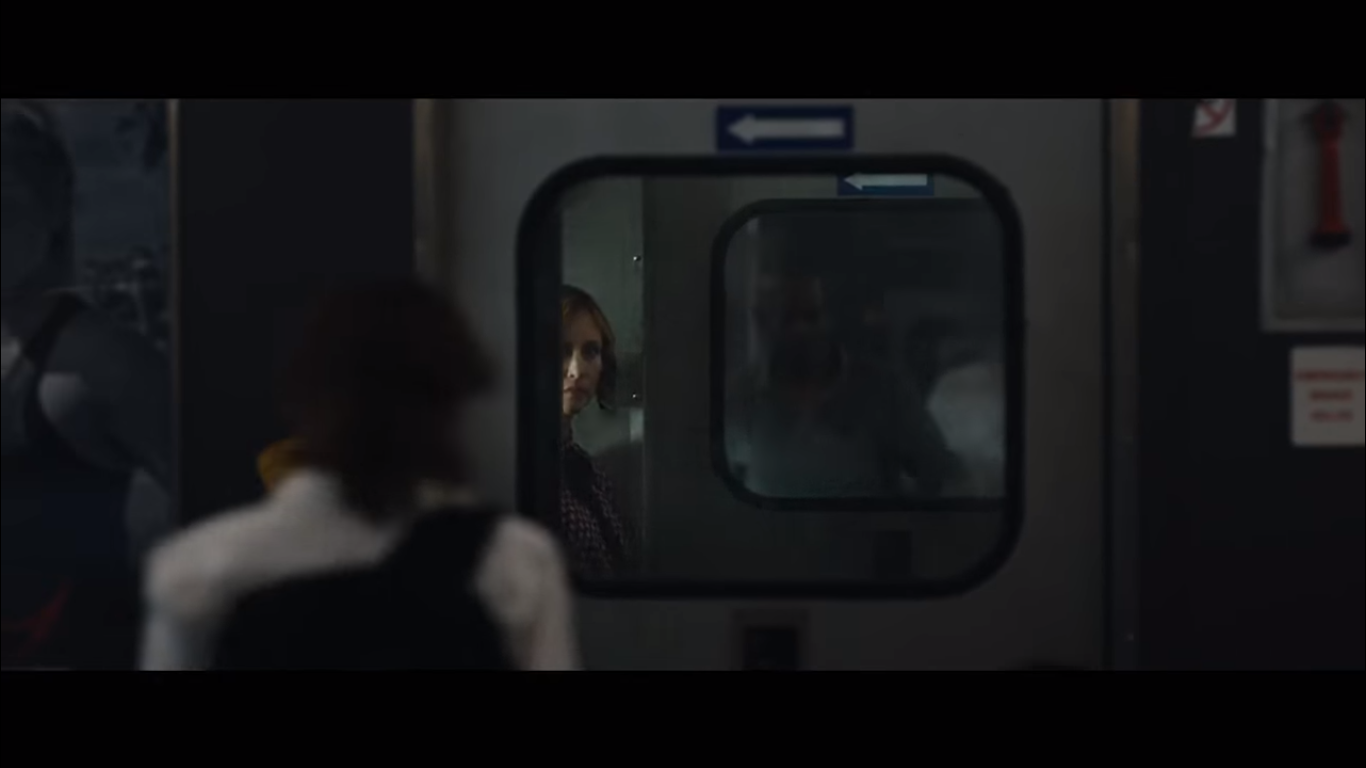

The train, of course, is the ideal setting for this sort of affair. I’m a sucker for a good train movie — hell, I am a sucker for a bad train movie — and The Commuter leans into it. Neeson has a set of clues to go by as he determines who this person is, and also why he’s been targeted in the first place to play this opaque role. The train allows for both close confines inside and wide spaces seen from above, stillness amid velocity, and the introduction of characters both relevant and superfluous. It’s a classical trick deployed for genre reasons, and The Commuter is at its best when the contrasts are at their fullest: a douchebag investment banker for Neeson to bristle at on behalf of the middle class, the crouched figures hiding behind stationary chairs as the train speeds on, the barely-visible, half-reflected faces of ominous antagonists amid the crowd. As in Non-Stop, Collet-Serra relishes the visual and narrative possibilities.

The train, of course, is the ideal setting for this sort of affair. I’m a sucker for a good train movie — hell, I am a sucker for a bad train movie — and The Commuter leans into it. Neeson has a set of clues to go by as he determines who this person is, and also why he’s been targeted in the first place to play this opaque role. The train allows for both close confines inside and wide spaces seen from above, stillness amid velocity, and the introduction of characters both relevant and superfluous. It’s a classical trick deployed for genre reasons, and The Commuter is at its best when the contrasts are at their fullest: a douchebag investment banker for Neeson to bristle at on behalf of the middle class, the crouched figures hiding behind stationary chairs as the train speeds on, the barely-visible, half-reflected faces of ominous antagonists amid the crowd. As in Non-Stop, Collet-Serra relishes the visual and narrative possibilities.

By the time the ride is through, The Commuter will have run through any number of possible resolutions, like an insurance salesman crunching numbers. The appearances of a bearded Sam Neill and fellow cop Patrick Wilson (who, along with Farmiga, distractingly implies this might turn out to be a secret Conjuring sequel) complicate matters for our commuter. A guy gets smashed in the face with an electric guitar. So forth.

By the time the ride is through, The Commuter will have run through any number of possible resolutions, like an insurance salesman crunching numbers. The appearances of a bearded Sam Neill and fellow cop Patrick Wilson (who, along with Farmiga, distractingly implies this might turn out to be a secret Conjuring sequel) complicate matters for our commuter. A guy gets smashed in the face with an electric guitar. So forth.

In its closing moments, The Commuter resolves so neatly that the effect is comic. Collet-Serra seems to smirk before the credits roll, it’s so over the top. Which does raise the question, here, of how seriously we should take material the film itself finds farcical, and also, retroactively, how much I should fault the corn stuff in his previous outing. Popcorn entertainment, indeed.

Despite that, or maybe because of it, The Commuter works on several levels — as a deconstruction of the hero, a tweak on the genre, a train movie, a jerky-cam action thingababobber, and a comedy. There is a “Spartacus moment” that led to actual applause from my fellow moviegoers, and knowing applause at that — “oh my god,” followed immediately by laughter and appreciation. The ludicrousness isn’t an accident, and it’s not nearly as stupid as it first appears. (Ok, it’s still pretty stupid, but a particular kind of stupid.)

Collet-Serra’s high-velocity, high-stakes room escape narratives are rooted in almost existential treatments of individual choice, which ground them in something unusually gripping for movies that also include a Jason Bourne-like 60 year old almost being crushed by the falling debris of his own dilemma. The Commuter is much smarter than it needs to be for something so dumb.