The Big City, Indian master Satyajit Ray’s deeply feminist and empathetic 1963 depiction of a changing Calcutta, is nearly perfect in every way.

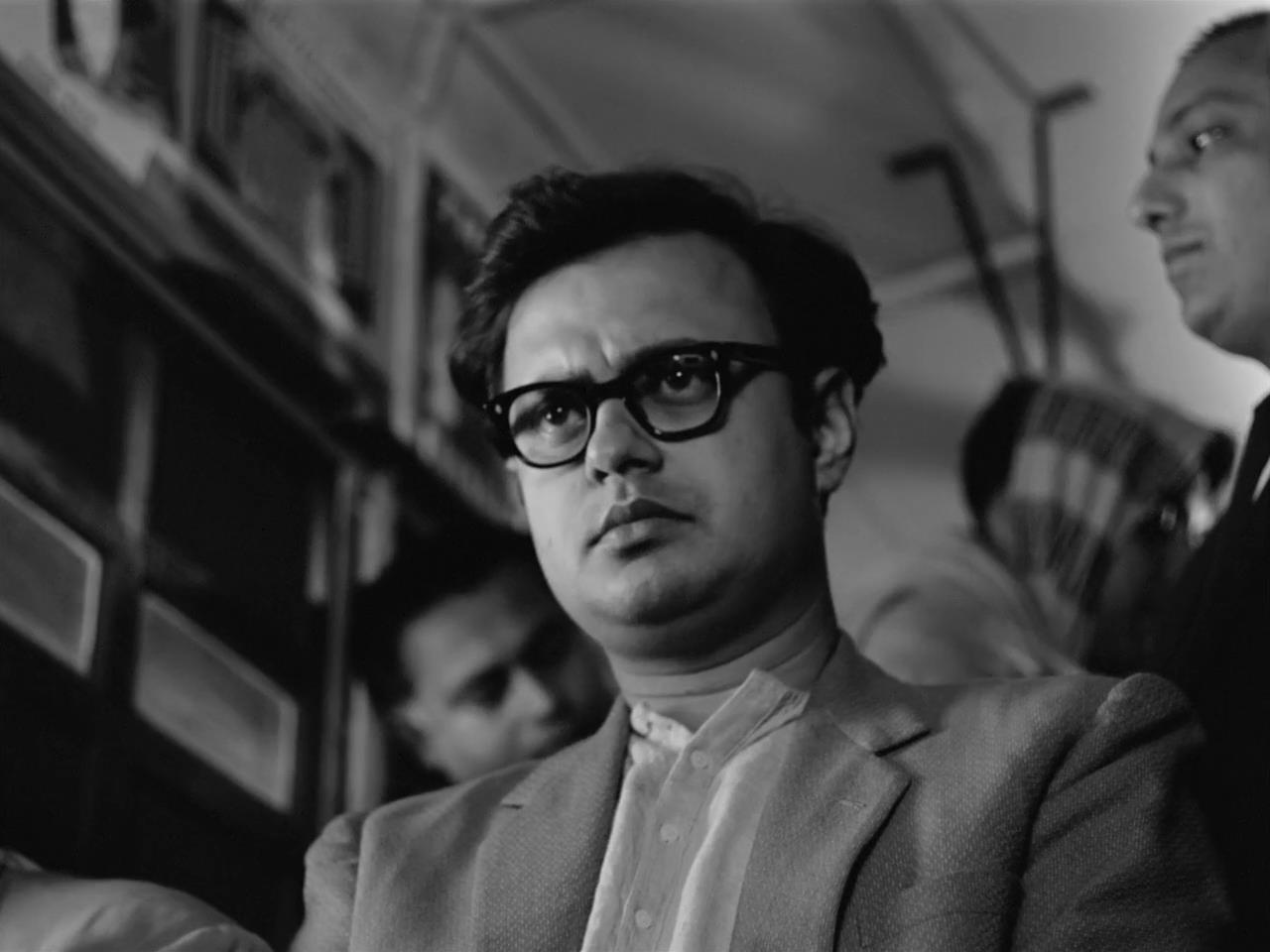

With nuanced performances, especially from the luminous Madhabi Mukherjee as Arati Mazumder and Anil Chatterjee as her wry, conflicted husband Subrata (Bhambal), and an effortless sense of place, custom, and the economic pressures that challenge tradition, the film is an utterly absorbing experience, by turns uplifting and heart-rending. It draws from both melodrama and neorealism, creating something entirely unique – an honestly felt love story about family, freedom, and the hope for a better day against continually crushing odds.

Ray exploded onto the scene a decade prior with Pather Panchali, often considered the first international arthouse hit. The influence of that film, the first in Ray’s Apu Trilogy, is hard to overstate, if its long list of vocal admirers is any indication (François Truffaut, Abbas Kiarostami, and Wes Anderson among them). Characterized by subtle textures, a languid pace that matches that of the village in which they are set, and naturalistic performances, they were immediately recognized as masterpieces of cinema.

At the start, The Big City shares much with his earlier work. We open in the Mazumder house in Calcutta, which is small but warm, and filled with life. Subrata and Arati give the immediate sense of a loving couple, his teasing eliciting knowing smiles and slight sarcasm as they start their day. His sister lives there as well, also receiving her fair share of teasing, while the youngest child plays games off in a corner, occasionally piping up with something adorable. Subrata’s parents also live here – the house seems full but happy.

At the start, The Big City shares much with his earlier work. We open in the Mazumder house in Calcutta, which is small but warm, and filled with life. Subrata and Arati give the immediate sense of a loving couple, his teasing eliciting knowing smiles and slight sarcasm as they start their day. His sister lives there as well, also receiving her fair share of teasing, while the youngest child plays games off in a corner, occasionally piping up with something adorable. Subrata’s parents also live here – the house seems full but happy.

In a wonderful touch, the camera often remains stationary as people come and go through what seems an endless series of doors, popping in to add to the conversation or just on their way elsewhere. The effect would be stage-like except for how gorgeously it is shot, and eventually the camera does track them in turn through the house, becoming more reminiscent of Altman or early Linklater than the theater. It’s quintessentially cinematic, but also understated. There’s no rush, and the audience feels like their getting a glimpse into real lives.

Eventually, the story kicks into gear. Subrata works at a bank but money is tight. There is food for three days, but no one seems too concerned about this – it seems there is also enough money for three days. Plans are made for months down the line, once he can land a part-time gig. But upon hearing that one of his friend’s wives has taken a job, Arati determines to do the same. This will have consequences big and small.

She lands a gig as a salesgirl, selling a knitting machine door to door. In one of the great sequences, not only of the film but of cinema, she and her fellow trainees hit the streets to sell their wares, and the previously stately camera turns shaky and hand-held, reflecting their anxiety. But also their pride: one by one, the hand-held 16mm tracks backward as the women walk with determination towards it. The intent and effect are clear: the women are coming, and this is a new day. The expressions on their faces are intensely affecting. There is freedom, exuberance, and apprehension in equal measure. Ray’s depiction is flawless.

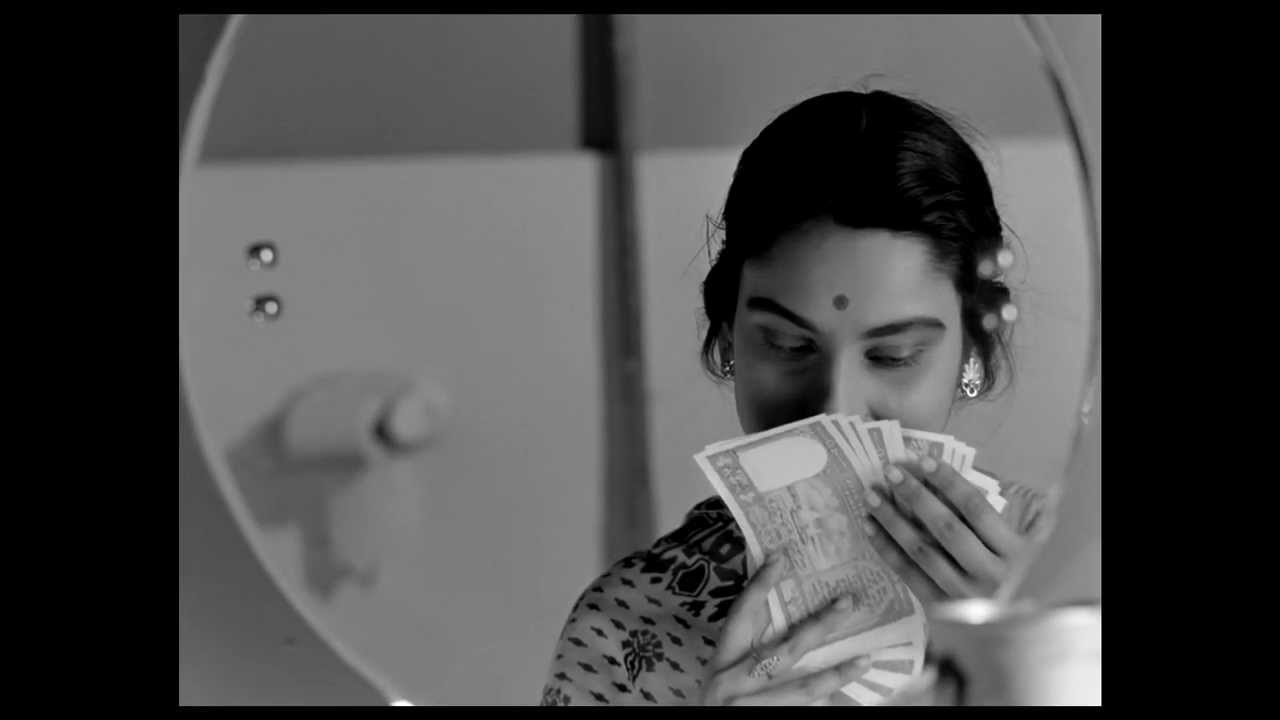

It turns out Arati is exceptionally good at her new job, and before long is making more than her husband. Her father-in-law, bound by tradition, was already dismayed by the situation, refusing to talk to the family or accept gifts bought with this ill-got money, from a housewife employed outside the home. Now Subrata, formerly seeming quite progressive and practical about the whole thing, now feels a sting, too. Even young Pintu resents his mom’s absence (though he can bought off fairly easily, if temporarily, with new toys). Subrata demands she resign for the good of the household, promising to get that part-time job at once.

It turns out Arati is exceptionally good at her new job, and before long is making more than her husband. Her father-in-law, bound by tradition, was already dismayed by the situation, refusing to talk to the family or accept gifts bought with this ill-got money, from a housewife employed outside the home. Now Subrata, formerly seeming quite progressive and practical about the whole thing, now feels a sting, too. Even young Pintu resents his mom’s absence (though he can bought off fairly easily, if temporarily, with new toys). Subrata demands she resign for the good of the household, promising to get that part-time job at once.

Fate has other things in store, however. The economic climate, particularly among upstart banks who aren’t exactly on solid ground with their clients’ money, intervenes, and Arati retains her position; in fact, she’s even offered a promotion. But a final twist, a moment of sisterly solidarity with a fellow worker, complicates things further, and seems to leave the couple worse off than they started. But the film’s final moments reveal the depth of their love, of his respect for her integrity, and their shared determination to forge ahead. The gorgeous closing shot finds them smaller and smaller as the camera cranes above, just two lovers in a tumultuous city, down but certainly not out. And they have each other.

There are many other delightful touches and indelible moments, but they should be experienced cold. Ray’s genius is on evidence throughout in the framing, the pacing, the totally sincere dialog and characterization. The camera work is as good as it gets, and the exploration of tensions between home and freedom, the individual and society, the desire to do what’s needed and the impulse to do what’s right feel contemporary at every turn. This is a film that cannot date itself – The Big City shows that, even if the details change, those tensions will always be deeply felt. And it shows this and more with the effortless grace of one of the true masters of cinema.