The term “melodrama” gets a bad rap these days, implying artificially heightened emotions and stagy, contrived narratives, but few genres or tendencies have held such continuing appeal over time. In the silent era, these were more the norm than the exception, and Teinosuke Kinugasa‘s Crossroads (1928) shows this to be as true in Japan as anywhere else in the film-making world.

Crossroads (sometimes translated as Crossways or Slums of Tokyo; the original title is Jûjiro) is a “weepie,” to be sure, but a fascinating one. Rikiya and his sister Okiku live in the Red Light District of 18th c. Edo, struggling to get by. Or rather, she struggles, mending clothes and performing odd jobs to keep the two of them afloat. Rikiya spends most of his time in town, infatuated with the courtesan O-ume. Unfortunately, O-ume is both desired by every other man in town, including some very powerful ones, and also treacherous and vain. Figuratively blinded by a distinctly pathetic version of schoolboy love, he ends up squaring off with one of her paramours and is literally blinded from ashes thrown in his eyes. His helplessness only increases the burden on Okiku.

To make matters worse, he believes he’s killed the rival suitor, placing both him and his sister in a precarious position. As he holes up in their apartment and she tries to negotiate these dangerous waters, the world impinges on them both. Kinugasa finds shadows even in the darkness they live in, which is occasionally near-total. There is little light, and little hope for redemption. All the figures in the story either want something from Okiku or strategize how to best exploit Rikiya’s situation. This is an unforgiving world that punishes people for having the temerity to fall in love.

To make matters worse, he believes he’s killed the rival suitor, placing both him and his sister in a precarious position. As he holes up in their apartment and she tries to negotiate these dangerous waters, the world impinges on them both. Kinugasa finds shadows even in the darkness they live in, which is occasionally near-total. There is little light, and little hope for redemption. All the figures in the story either want something from Okiku or strategize how to best exploit Rikiya’s situation. This is an unforgiving world that punishes people for having the temerity to fall in love.

On the other hand, Rikiya makes pretty awful choices all along the way, and the rigid gender structures (not to mention his unquestioning belief that his sister ought to be supporting him) make him a bit hard to root for. That may just be imposing a modern sensibility on an old film looking back on an even older age, but it can’t be ignored. When he collapses in tears upon being challenged for his lover’s hand, he makes for a particularly pathetic and useless figure, especially compared to his stoic sister, who actually tries to solve problems and take care of things on the day to day.

In the end, it doesn’t matter. In classic melodrama fashion, the facts of the world are immovable and the choices that have been made irrevocable. Things are headed for a fall from the start. In the meantime, though, Kinugasa fills the frame with impressionistic touches that put us fully in the place of the characters. Some are pretty bold — he deploys superimpositions and double exposures and a spinning camera, turning wheels and rotating lanterns as motifs. Crossroads flashes back and forward with ease, emphasizes the rush of memory through quick cutting, and fades to bright lights and what seems to be falling snow to indicate wounded eyes struggling to come into focus. The decision to position us in individual characters’ points of view, visually, is an unusually evident stylistic choice for 1928.

In the end, it doesn’t matter. In classic melodrama fashion, the facts of the world are immovable and the choices that have been made irrevocable. Things are headed for a fall from the start. In the meantime, though, Kinugasa fills the frame with impressionistic touches that put us fully in the place of the characters. Some are pretty bold — he deploys superimpositions and double exposures and a spinning camera, turning wheels and rotating lanterns as motifs. Crossroads flashes back and forward with ease, emphasizes the rush of memory through quick cutting, and fades to bright lights and what seems to be falling snow to indicate wounded eyes struggling to come into focus. The decision to position us in individual characters’ points of view, visually, is an unusually evident stylistic choice for 1928.

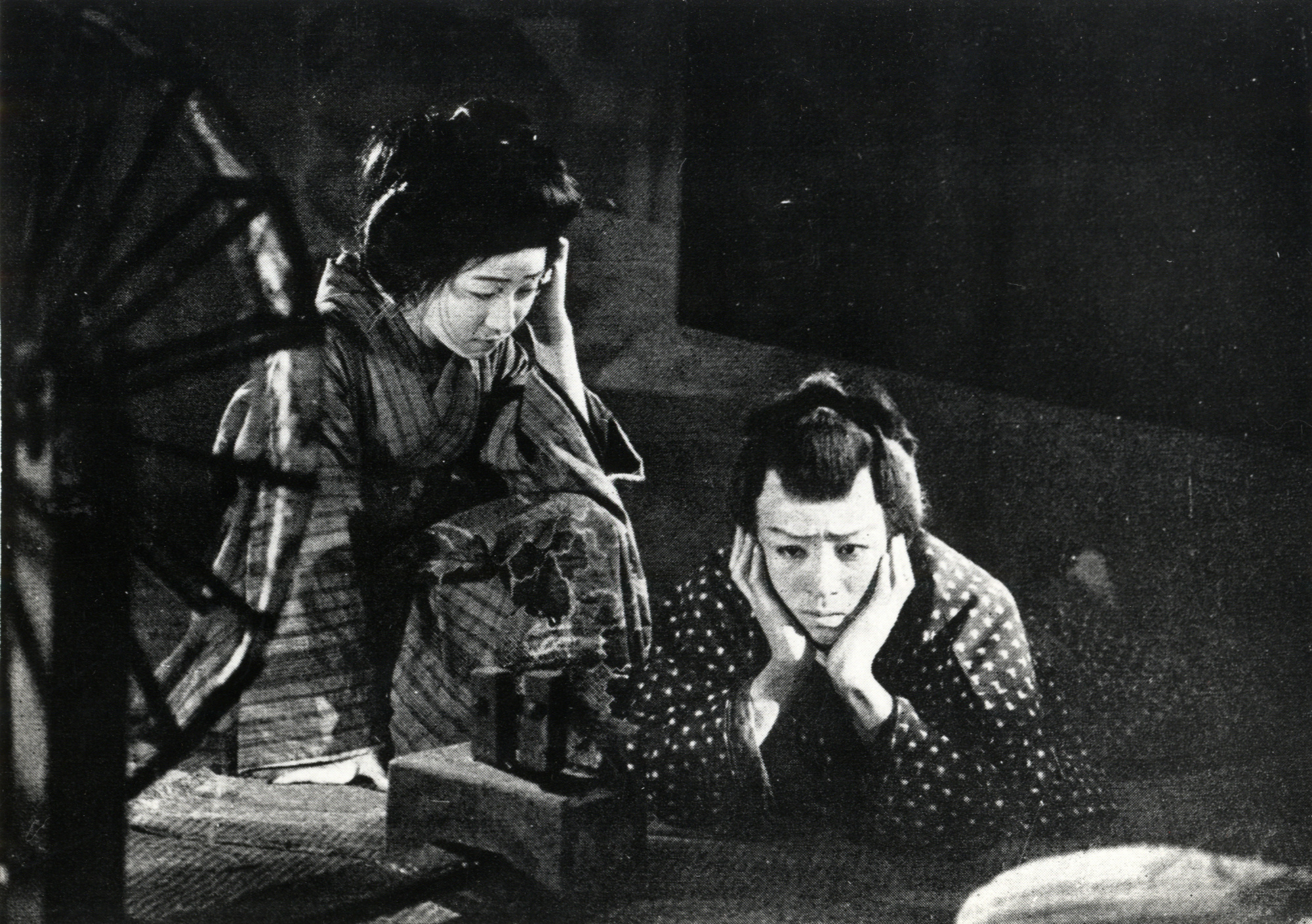

There are several touching scenes between the brother and sister as she nurses him back to health. There’s a sense that family provides the only solace in a world marked by cruelty, rapaciousness, and greed, though this glosses over the fact that he’s as reckless as she is faithful. Still, as in all good melodrama, you hope things will work out for these people, even as you become more and more certain they simply can’t.

From a historical angle, and from the vantage point of this series, Crossroads is also interesting as an example of the collision of early cinema and regional stage conventions, in this case kabuki. Kabuki is no stranger to notions of heightened emotion and exaggerated behavior, and I wonder to what degree silent films played differently for Japanese audiences than they may have for others. I don’t have any idea, but it’s a thought that kept bouncing around throughout the film — the characters are archetypes even more than they would’ve been in many Western films of the period, and perhaps this fits in with particular cultural expectations of art. (Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood springs to mind, a Macbeth stripped of individual characterization and writ large.) At no point in Crossroads does anyone bother to provide a back story — we never even find out why Rikiya and Okiku are in such desperate straits, or where the rest of their family is (though Okiku states her brother is “all she has”). It’s as though Kinugasa is simply saying, “This is how things are.”

Still, the fundamental techniques of the silent film that Kinugasa uses tend to neutralize this sense — the close-ups are luminous, the motivations of the individuals (particularly Okiku) clearly delineated and felt, and the overall sense seems closer to modern, small-scale tragedies than epic, ancient portrayals of larger-than-life people and the collapse of order. With all the cinematic techniques he could muster, Kinugasa finally tells a personal, sad story of life on the margins, and how some people just can’t catch a break.

Part of an ongoing effort to watch a set of films from non-White, non-U.S., non-male, and/or non-straight filmmakers and depart a little from the Western canon. The intro and full list can be found here.

Next up: Mario Peixoto’s Limite.