In Kelly Reichardt’s masterful 2013 meditation on terrorism Night Moves, we’re slowly introduced to a trio of disaffected young people staging a dramatic intervention: the explosion of a dam. Memorably, and in true Reichardt fashion, that explosion, which by all standard narrative conventions should occupy the film’s central spot, registers in the narrative instead as a muted, distant noise. The real drama lies with our conflicted protagonists, not their plot. Bertrand Bonello‘s Nocturama is up to a similar sleight-of-hand.

But Bonello is way too much of an aesthete to deprive us of the fireworks entirely. And why should he? Against a canvass of casual nihilism and consumer fetishes, Nocturama sketches blown-out windows and a burning Joan of Arc statue as though they were simply the end-games of a youth culture with little to grip onto in the first place, apart from how pretty things look when they’re on fire.

We meet our anti-hero protagonists, 10 of them in all, in a silent, circuitous procession through the Paris Metro. Bonello knows we will try to piece together their aims, and so he’s right. Wordlessly, they meet up on trains, pass by each other on streets, and generally emanate an ominous mood that something is afoot. They are, by turn, over-privileged children of the white establishment, shy Black youths, possibly second-generation Muslim 20-somethings, security guards, and more. There is no throughline provided, and, as Nocturama winds its way to the inevitable, no motives explained: no fiery speeches, only the faintest articulation of social outrage. Perhaps they simply want to watch the world burn.

Nocturama is almost perverse in its insistence on surfaces and sheen. What little is said can be taken many different ways, and their impromptu dance parties only underscore a lack of affect. Again and again, Bonello emphasizes the vapidity of culture, and also the desperate desire of even its enemies to enact it. Nocturama is art-house cinema with a bomb in its backpack.

Eventually, fleeing from their simultaneously orchestrated attacks — which, though they insist casualties are to be minimized, also involve straight-up quadruple homicide — the dwindling members of this ersatz cell take shelter in a lush, shuttered department store (in fact, the Samaritaine, the same one Leo Carax featured for the Kylie Minogue segment in Holy Motors, as Richard Brody points out in an atypically acerbic pan that stinks of decades-old ideology and willful misreading).

There, we enter Dawn of the Dead territory, as Bonello channels cinematic flash-points one after the other, without ever digging very deep. Why would he? In a film of surfaces and malaise, such an expectation seems out of place. The pulsing unease of the first half of the film is replaced with frightened camaraderie and make-believe, as the indefinable terrorists spend a night trying on clothes and wallowing in the shallowness they (allegedly) mean to disrupt.

Nocturama is a slow-moving trainwreck of anti-ideological whims and vaguely grasped desires. All the leads are strong, and the film’s ultimate trick is to make you at least start to care for these people, even though there actions have been provided little to no justification.

On the street outside the Ballardian enclave, one character has slipped out to have a smoke. He asks a bystander what’s been going on. She shrugs and says, “It was bound to happen.” In the absence of unifying forces, apart from cell-solidarity, or anything approaching class-consciousness, we are left with surfaces, and we are made of those surfaces, too. That the kids should blow up a government building and escape to stage a fancy dinner of stolen goods in newly-acquired luxury wear makes all too much sense. As does the violence — calm, unsparing, nastier in its silence than it would be at full volume. It was bound to happen.

(Streaming on Netflix)

Quick Links

As long as we’re talking about films by unapologetic aesthetes with references to night in the title, there’s also Tom Ford’s Nocturnal Animals. It’s actually curious to think what this former fashion designer would’ve made of Nocturama, and what Bonello would’ve done with this story-within-a-story-within-a-story.

Where Nocturama takes its title from a phrase denoting where zoo animals are kept at night, Nocturnal Animals refers both to itself as well as the novel that Jake Gyllenhahl’s sensitive writer character delivers to his gallery-owning ex-wife (Amy Adams). In neither case do things end well.

Those allergic to meta-narratives and ostentatiously tricky time-stamps won’t much care for either, but both films have so much style it’s impossible to dismiss them completely. Here, we are introduced to Gyllenhahl’s protagonist setting out across West Texas with his wife and daughter; the genre trappings weigh heavy on the evening.

It’s no real surprise when back-country monsters intercept them — first, as road warriors playing dangerous games with cars, and then as out-and-out kidnappers who steal his family away for nefarious purposes. (Aaron Taylor-Johnson‘s shudderingly eerie leader of the pack reveals previously unknown capabilities for the actor.)

Barely escaping, Gyllenhahl winds up paired with Michael Shannon’s pulp-cowboy-detective (so good), a sort of nothing-left-to-lose remnant of an earlier mythology of the West. They’re out for justice, but it’s clear justice won’t be pure.

This is the stuff of serialized Westerns, cross-bred with exploitation. It’s also the plot of the book that Amy Adams’ Susan is reading, which provides an entrance way into flashes of memory, particularly her relationship with ex-husband Edward (also Gyllenhahl). Is the book an elaborate metaphor for a shared trauma in “real life”? The actresses who play the novel’s wife and daughter are dead ringers for Adams and her daughter.

On top of this, there’s a third narrative woven through, as Susan tries to recontact Edward, profoundly moved by his novel. Ford showcases Susan’s isolation in the loveless marriage of privilege to the man she wedded to ensure a future. She stages gallery centerpieces of obese women dancing, which Ford films in slow-motion (natch). It would be grotesque if it weren’t so sad and unnerving.

The pervasive sense of emptiness and haunting is almost too much, at least in Ford’s hands, and reactions to the film were unsurprisingly mixed. But it’s impossible to look away.

(Streaming on Amazon Prime)

Butter On The Latch / Thou Wast Mild And Lovely

Josephine Decker is a singular talent, and her one-two punch of Butter on the Latch and Thou Wast Mild and Lovely confirm this.

The two films, released nearly simultaneously, bookend each other. The horrors of the first are entirely internal; in the second, they spill over into third-act schlock that only an arthouse exploitation fan could love.

But in both, the central female protagonists wander through unsure terrain, bucolic evocations of the feminine that turn either threatening or empowering (depending on where you’re seated). And in both, the visuals are remarkable, paired with a mumblecore / performance-art improvisation style that suits the mood.

Whether you want anything to do with this mood is a matter of taste. I’m not sure Decker cares one way or the other.

(Streaming on Shudder)

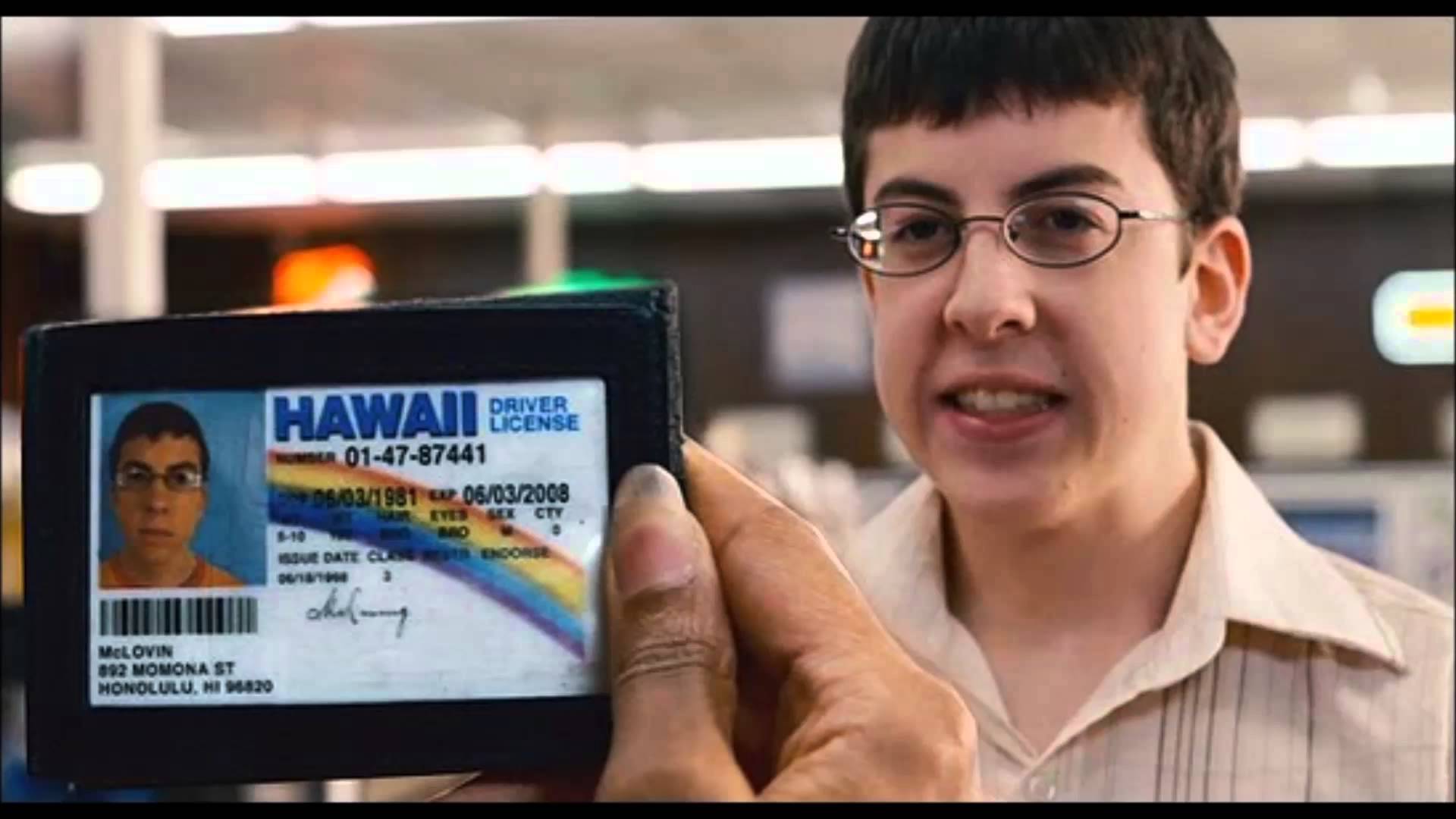

Still the sweetest of that increasingly irritating Apatowian genre — the nerd wish-fulfillment narrative — Superbad gets points on rewatch for actually playing with the formula. (The funniest scene to me now is Michael Cera and Jonah Hill awkwardly trying to talk their way out of waking up a little too close, in dialog that self-consciously brings to mind a one-night stand.)

But no one’s watching Superbad for its analysis of male bonding and the very real anxieties of heading off to college, realizing you might’ve just wasted your teenage years doing fuck-all with your loser friends. We’re watching it for the one-liners, and they’re still pretty funny.

(Streaming on Amazon Prime)

This Is Spinal Tap / Following / Cronos / Eraserhead / The Duelists / Hunger / Sweetie / Blood Simple / Mala Noche / Poison / Stony Island

Jason Bailey pointed this out two weeks ago, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t echo it. FilmStruck has a series of First Movies, and it’s a doozy.

(Streaming on FilmStruck)

David Lynch on the History of Surrealist Cinema

Have you calmed down about Twin Peaks: The Return yet? No?

Well, then perhaps you’d like to hang out with your buddy David Lynch, circa 1987, and watch some shorts and excerpts from films he’s enjoyed.

Lynch has never really been a Surrealist, but that hasn’t stopped anyone from describing him as such over the years. For the BBC, he leaned into the characterization. The result, complete with a shitty VHS transfer, is always here for your perusal.

(Streaming on dailymotion, via OpenCulture)