October horror update, the Twenty Seventh Day of the Tenth Month in the Year of our Lord Two Thousand and Sixteen.

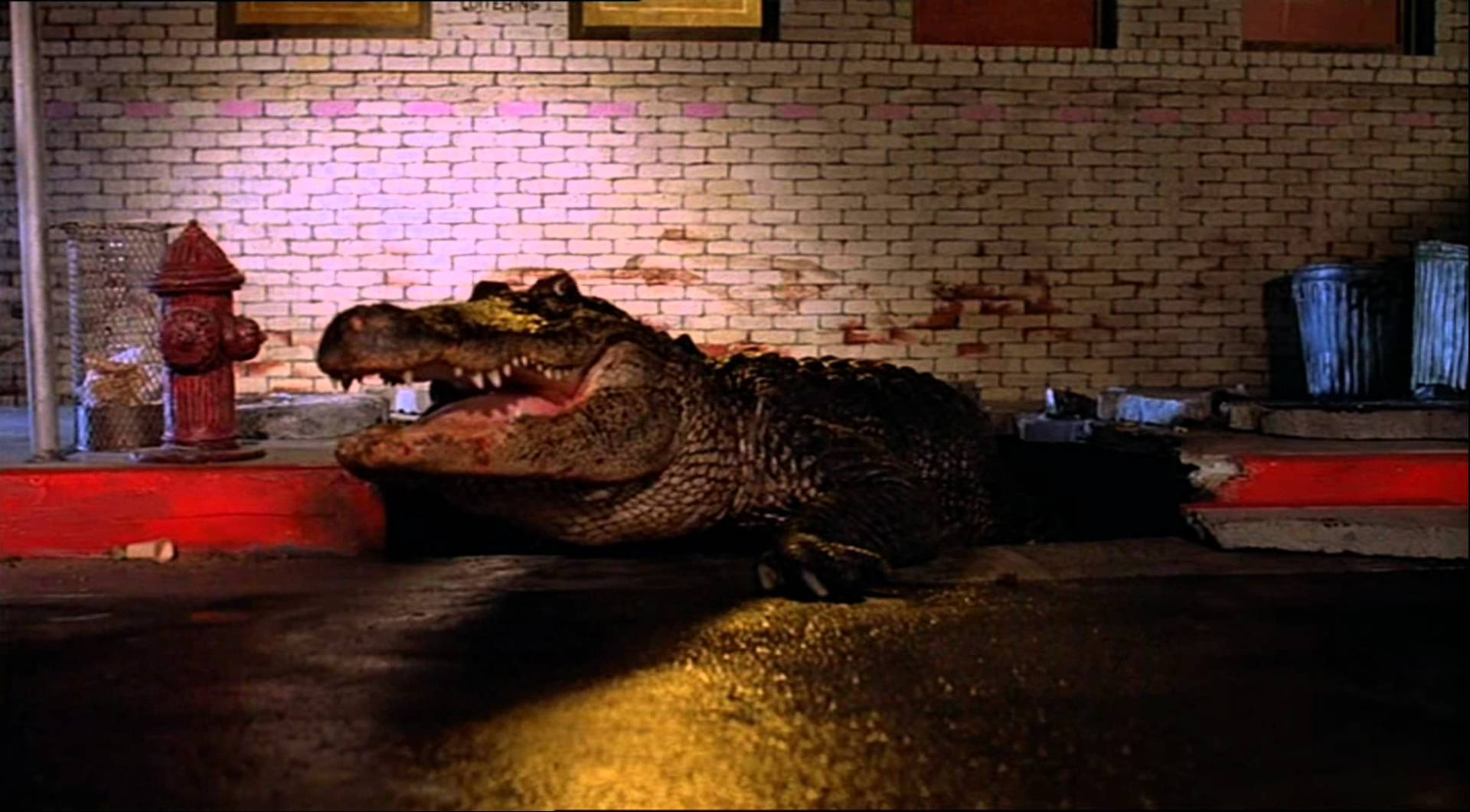

Alligator (U.S., 1980, crazy animal)

Or as I prefer to call it, “Alligator, A John Sayles Film“.

It’s true that Sayles’ first screenwriting credit is for Piranha, the Joe Dante schlock classic, which he followed up several years later with werewolf standard The Howling. Sayles no stranger to low-budget horror. But there’s still something vaguely amusing about the esteemed auteur who brought us Matewan, Eight Men Out, and Lone Star charting out the plot-beats for a film in which Robert Forster tracks down mutant sewer alligators and obsessively worries about his male pattern baldness.

Alligator is fun for exactly this reason: it’s entirely competent and a little bit odder than it really needs to be, perhaps reflecting a good writer diving deep for things to entertain himself amid the Crazy Animal hijinks. Playing off the enduring urban legend of pet alligators flushed down city toilets and growing to enormous proportions underground, Alligator makes the odd decision of becoming a police procedural. It’s basically the story of how a deeply committed cop — on the outs with his superiors, grappling with previous trauma and anxiety about growing old — foils a serial killer. It’s just that the serial killer happens to be a mutant reptile.

I expected little from this film and was delighted. File under: not precisely October Horror, much better than an alligator movie needs to be.

Night of the Demon (U.K., 1957, before 1970, witch/witchcraft)

In his 1940’s films for RKO, especially the Val Lewton-produced Cat People and I Walked With A Zombie, Jacques Tourneur generated scares with almost nothing but shadow, tension, and a sense of the uncanny. For Columbia a decade later, his Night of the Demon pulls out some of the same tricks.

Like both those earlier low-budget affairs, Night of the Demon contrasts the rational and the supernatural, though here it becomes much more explicit. An American professor arrives in the U.K. to give a talk about “parapsychology”, specifically the ways death cults operate and how people are tricked into believing in demons and ghosts. Instead — wouldn’t you know it — he finds his faith in logic shaken when confronted with actual witchcraft and esoterica.

A whole paper could be written about the implications of this confrontation between new and old worlds, reason vs. the inexplicable supernatural. Or we could just enjoy the beautiful photography and an October Horror entry that fire-monsters its way through the narrative at an appropriately breakneck pace.

Eaten Alive (U.S., 1976, crazy animal, Tobe Hooper)

Confession: I turned this on expecting to watch Umberto Lenzi’s cannibal film Eaten Alive! Instead, I found myself in a coked-up Tobe Hooper fantasia. I’m not sure which would’ve been more pleasant.

Eaten Alive certainly wouldn’t get saddled with that description. Hooper’s bloody, scythe-wielding, throat-slashing, child-shrieking, alligator-mauling, cowboy-hatted Texsploitation follow-up to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre seems almost fixated on delivering the gore its wildly successful predecessor did not. This is understandable, but slightly disappointing, as the lack of gore is one of Texas Chainsaw‘s most fascinating characteristics.

On the other hand, this is a bonkers entry in Hooper’s odd filmography. Right from the outset, Eaten Alive announces it intends to test your patience, and as the film progresses, this only becomes more clear. There’s a lot of incoherent mumbling, banging and screaming and gratuitous stabbing here. But there’s also an assured use of smoke and mist, a constant soundtrack of country and Tejano music adding something incongruous, and splashes of Argento-inspired color saturation. The very fact that the Psycho-esque motel doubles as a zoo, with its primary feature being a voracious alligator (or crocodile, no one is ever certain) in the front yard, places Eaten Alive in some weird netherworld, a nightmarish and lurid locale filled with maniacs, brothel owners, and people lost at night.

Or maybe that’s just Texas.

Fright Night (U.S., 1985, original + remake)

After checking in on the hyper-self-aware Fright Night from 2011, it was interesting to jump back 27 years to the original. There are jokes here, and it’s fun to map Marti Noxon’s genre tweaks, but Tom Holland’s 1985 horror-comedy is surprisingly heavy on the horror. Several of the transformation scenes are legitimately gross and gripping, and Chris Sarandon’s impossibly 80’s vampire is creepy from the get-go. Even the irritating friend — who Noxon does a particularly good job fleshing out in the remake — becomes a source of eeriness and pathos by the end of the film.

For some reason, Fright Night was relegated in my mind to pure camp silliness, but it’s actually a nifty little vampire movie.

Martin (U.S., 1977, Romero)

George Romero’s melancholy, quasi-vampire tale Martin is the most unexpected movie on this October horror list, and the less you know about it beforehand, the better. One of its primary joys is guessing where Romero is headed next. Suffice to say: rather than the grislier aspects of Night of the Living Dead and its progeny, Martin has more in common with arthouse fare. It’s quiet, subdued, intent on undermining its genre trappings. Its title character may or may not be Nosferatu; the horror may lay elsewhere. Romero shoots small-town Pennsylvania with the eye of a resident, firmly grounding terror in the mundane and making things all the more terrifying for it.

But somewhere in its heart or thereabouts, this is also a film about depression and alienation. Many vampire stories dwell on loneliness, but usually align that sensibility with the agelessness of its suave protagonists. Martin is not ageless, or suave. Romero’s film becomes a meditation on adolescence and desire. There’s plenty of blood, if that’s what you’re after, but the film leaves a different, creepier feeling in its wake.

The Mist (U.S., 2007, Stephen King)

Director Frank Darabont spent years trying to bring Stephen King’s “The Mist” to the screen. The result was, according to many, one of the great horror films of all time.

Others, myself included, watch it in frustration. There are so many good ideas here, but arguably too many to quite cohere. The film is at its best when, for the first half, the residents of a small town find themselves trapped inside a grocery store, surrounded by a mysterious, possibly chemical mist that is killing anyone who ventures out. Darabont draws out tension, fatigue, and creeping mania from the claustrophobic environment. In stage-play fashion, we enter a Sartrian world where hell is indeed other people: factions form, millenarian prophecies butt up against rational explanation, people’s worst impulses take hold.

By the time we venture out, we can only be disappointed by the monsters we find. (The CGI doesn’t help, though I’m told it works better in black and white.) The Mist ends on the most cynical of notes, a tragic collapse that Darabont fought for. It is indeed shocking.

But there’s still a sense of compromise: October horror viewers will not sit still for too long, you can hear someone saying, so the unknown has to be revealed. On top of that, Darabont insists on distractingly frequent shot-reverse shot constructions, soft focus, and swelling orchestration that weirdly undermines the horror.

The Mist works best before all that. And even with those critiques, it’s not hard to see why the film is so admired. The idea that the clouds rolling in hide something terrible, that they map onto what we can’t know about things surrounding us in plain sight, is a child’s fear. And horror, at its best, is a genre for children.