Actor, producer, and now director of The Invisible Vegan Jasmine Leyva doesn’t feel like mincing words.

When asked about why she wanted to make her new documentary-in-progress and how it relates to earlier films like Food, Inc., she responds:

Most of [the] experts are all white males; you don’t even introduce a POC until the 50-minute mark. Black vegans can feel invisible in their own community, and on the opposite side, you’re invisible in white spaces. It’s ok to be vegan, but not ok to be a Black vegan, despite how food impacts racial politics. You’re supposed to check your blackness at the door.

An independent production with a very clear point of view, Leyva’s labor of love follows in the ongoing tradition of folks like A. Breeze Harper, Food Empowerment Project‘s lauren Ornelas, and others, who work to center critical race theory and intersectional activism in the still-overwhelming white animal rights movement. The Invisible Vegan seems determined to upend stereotypes wherever it finds them.

During a brief but wide-ranging chat, Leyva told me about the motivations behind the film, and also what she’s learned as an independent filmmaker:

I think you have to just do it — when you’re female, you’re not upper class, you’re Black, people are not breaking down doors for you. So I learned: you know what? I’m going to use what I have and make what I can.

Ironically, this approach seems to accidentally echo the very foodways mentioned by several people in the above trailer, except in reverse — “make do with what you have.”

What’s inspiring is Leyva’s tenacity and forthright politics, which recognize contradictions and problems but stay grounded in a kind of compassionate assurance regarding nonhuman animals and the wider communities at large.

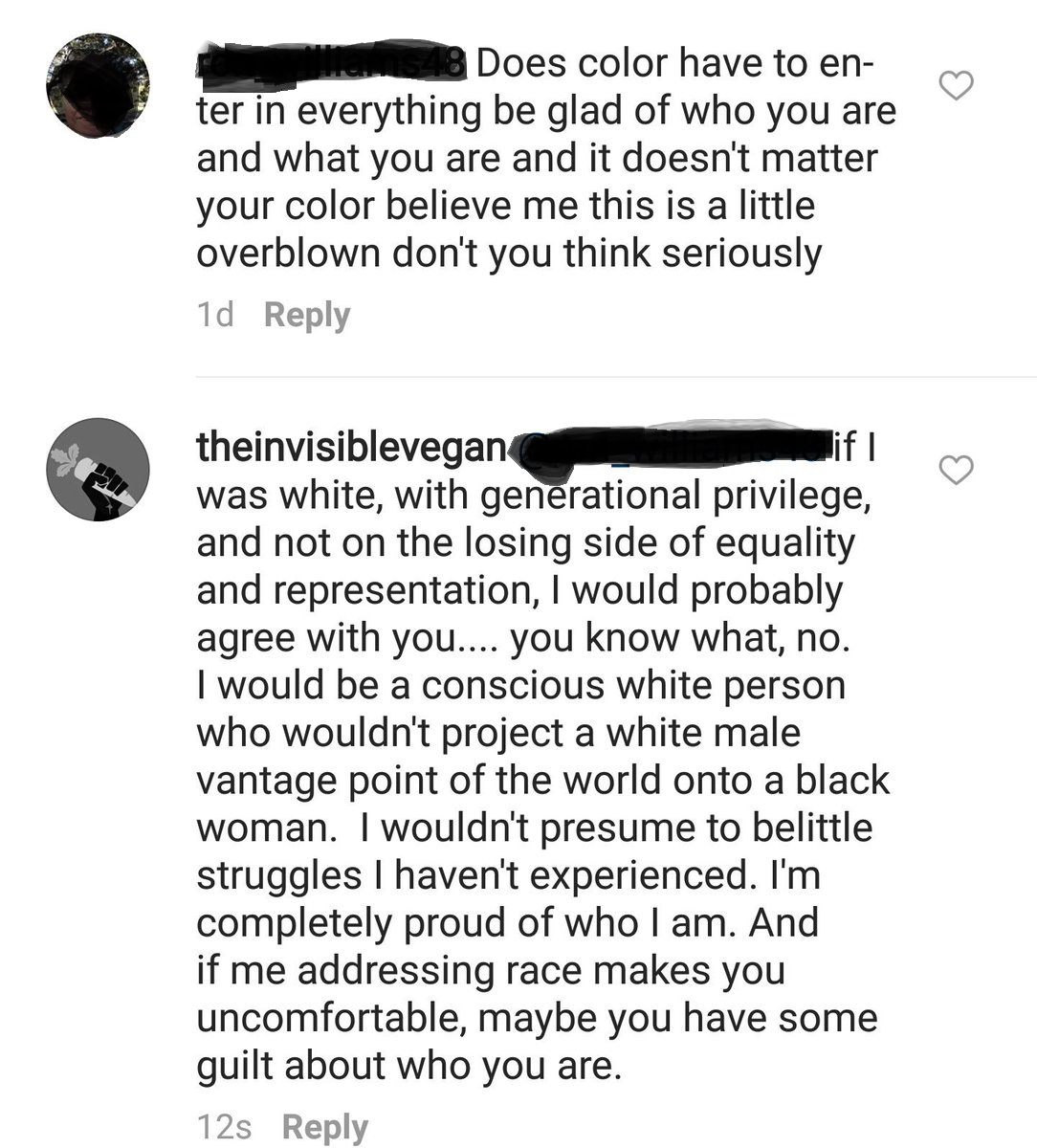

And, as ever, there’s no lack of (white) skeptics:

She also clearly knows her history, which The Invisible Vegan, with its title riffing on Ralph Ellison’s classic, promises to detail further. “[The Invisible Vegan] attaches veganism to African roots,” she emphasizes. “When people think of ‘African-American food’, they think of soul food — but hey now! Our history didn’t start on a plantation.”

At one point in our conversation, I ask if she has any concerns about tokenism with The Invisible Vegan — I’m, after all, a white, straight, male, middle-class vegan asking her about her film. Animal rights efforts have been notorious over the years for this kind of thing, these blind spots and a prevailing sense of liberal do-goodism.

There’s a brief, total silence on the other end of the line. “You know,” I say, “maybe we should skip that. Maybe that’s not the best question for me to be asking.”

“Yeah. Alright,” Leyva says.

Moments later, halfway through the next question, she interrupts me. “Can we go back to that last one?”

“Of course!”

I don’t mind being a representative. But if it’s presented in a way that I’m one of the sole black women interested in veganism, then it’s a problem. If I’m one of the voices — and there are and have been lots of these voices — and then I’m ok with it.

The Invisible Vegan has its first screening on July 15th, with plans for wider distribution by the end of the year.