The nice thing about unique and distinctive voices (or those voices that you know, from general hubbub, must be unique and distinctive), across mediums and across genres, is that when you finally get around to experiencing them, they very rarely are anything like you assumed. I first remember reading about François Ozon in a book on the New French Extremity my first year of college, specifically in the context of Sitcom (1998). Even then, just from the description, it seemed weird to classify him and it alongside High Tension and Martyrs. Now, having seen it, it’s an even stranger classification.

The opening does seem to promise a Hanekesque dread-filled march into existential nightmare, as a patriarch returns home. The camera waits outside as we hear him shoot and kill his family.

Then, the flashback. It is weeks earlier and the family is alive, balanced for maximum future debasement: a father and a mother, a son and a daughter, and a maid (Spanish, and with an African husband; the mother’s Get Out-esque response promises racial commentary that never comes). The father (only the children — Sophie and Nicolas — have names, to further promise satirical universality) brings home a white rat, who begins to force the members of the family to act on their basest urges.

Then, the flashback. It is weeks earlier and the family is alive, balanced for maximum future debasement: a father and a mother, a son and a daughter, and a maid (Spanish, and with an African husband; the mother’s Get Out-esque response promises racial commentary that never comes). The father (only the children — Sophie and Nicolas — have names, to further promise satirical universality) brings home a white rat, who begins to force the members of the family to act on their basest urges.

So far, so new and French and extreme, although we seem to be closer to the Baise-moi end of things than the Inside end. But here Ozon throws in a twist for the too-clever viewer (like me). Because, with the possible exception of its first manifestation, it turns out that these deep, repressed desires the rat brings out (usually matched with a close-up of the bleach-white rat’s red eyes) are not quite as destructive as one expects.

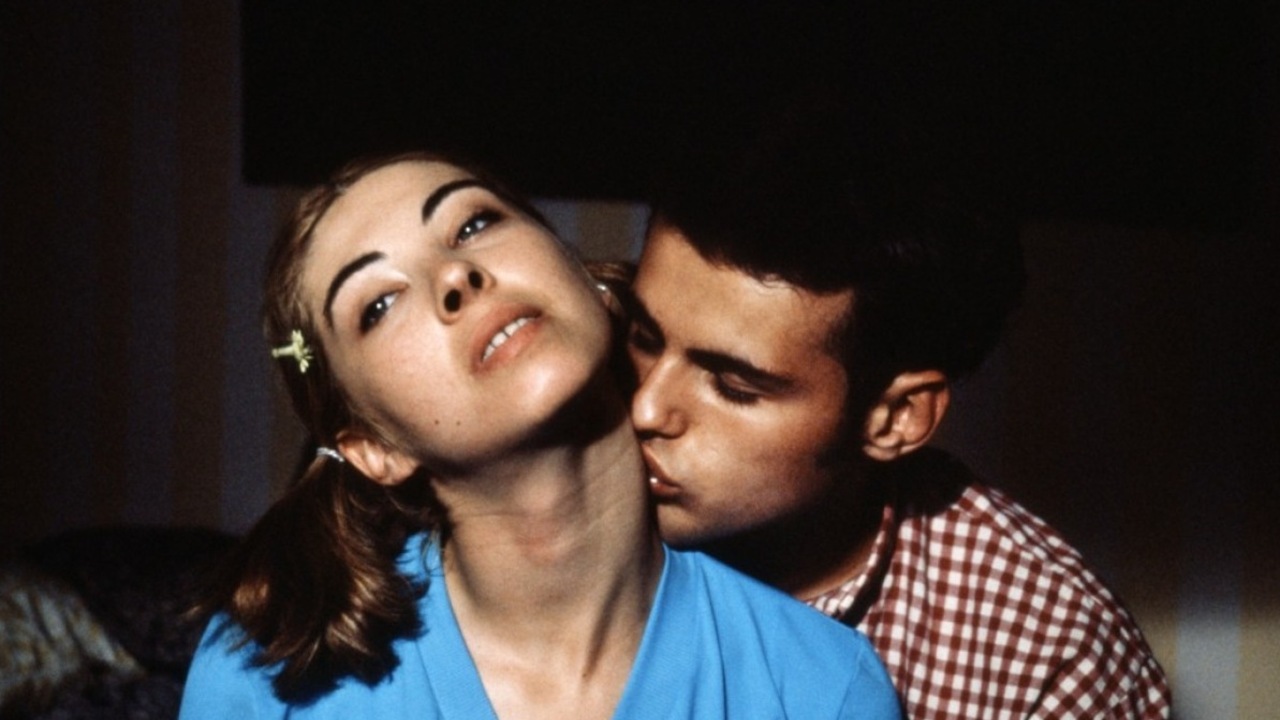

Even that first manifestation, a suicide attempt by Sophie that leaves her partially paralyzed, is not presented as particularly tragic. It certainly doesn’t get in the way of her sex life, as she enters into a sadistic relationship with her boyfriend (and which she describes to her mother). Most of Sitcom’s other characters’ un-repression is even more positive: Nicolas comes out as gay in the middle of a family dinner and ends up having a relationship with the maid’s husband and the maid stops working and mostly dances to records in the living room.

Eventually, la mere gets sick of the whole situation and — in the main taboo of the film, and the one that probably landed Sitcom among the NFE — tries to turn her son straight again by having sex with him. If anything would be the point of ultimate debasement, it would be this; but like everything else, Ozon shoots it with a cheerful objectivity.

All the cold repulsion one might expect from the camera ends up in the place of the father, who finally gets sick of the whole situation. There is a moment here that is the clear original end of the film: the father plays with the rat, gets the same red-eyed shot as everyone else, and we see the scene from the opening, in which he returns home and shoots everyone. Then, suddenly, at the sixty-minute mark, this is revealed to be a dream of his. (It’s a goofy decision, and I wonder who told Ozon he needed another fifteen minutes of footage.)

All the cold repulsion one might expect from the camera ends up in the place of the father, who finally gets sick of the whole situation. There is a moment here that is the clear original end of the film: the father plays with the rat, gets the same red-eyed shot as everyone else, and we see the scene from the opening, in which he returns home and shoots everyone. Then, suddenly, at the sixty-minute mark, this is revealed to be a dream of his. (It’s a goofy decision, and I wonder who told Ozon he needed another fifteen minutes of footage.)

Instead, his family, off at a spa, call to tell him of the rat’s evil powers, and he microwaves it and eats it. In the morning, his wife discovers he has become a giant rat; the rest of the uninhibited family team up to murder him, and the film proper ends not with his murder rampage the opening promises, but with his funeral.

Even when the film ended, I expected a final twist into dread — perhaps via a Marvel-style stinger — but it never came. The weirdest thing about Sitcom is how un-ironic the title is: it genuinely has the bouncy, positive, Full Housetian tone of a sitcom, just one with sadomasochism, homosexuality, and incest. It is a wonderful twist to have played on one, especially if it makes you realize, like I did, that you didn’t actually want to watch something that new or extreme anyway.