If memory serves, I was about 6 or 7 when I first saw George Romero’s The Night of the Living Dead. It’s one of those film-viewing experiences that left an indelible imprint: I distinctly remember that feeling of sympathetic helplessness, the emerging sense that this was not going to end well, along with the viscera and brutality, the total bleakness of the film’s climax. Even, or especially, pre-critically, without anything resembling a framework to process what I was seeing, Romero’s left-field, low-fi masterpiece appeared on the screen, and I ate it up like so many intestines. I’ve loved horror ever since.

Of course, sometimes memory doesn’t serve well. For one thing, why was this nightmare being broadcast on television in the early 80s, beamed into the Maryland suburbs on Sunday afternoons, at least in my telling? And why would anyone allow me to sit through a movie that prominently features a young girl devouring her father’s entrails?

It doesn’t add up. I’ve tried, gumshoe-like but in vain, to corroborate my own story. Did I dream this whole thing? Did I see it years later on VHS at a friend’s house, pilfered from someone else’s collection during the late hours of a sleepover? Or years later still, amid bong hits and cigarette smoke instead, and just remember it this way because I felt like a terrified child watching it?

All I know for sure is that when I rewatched it, yet again, the other night after hearing this towering figure in cinematic horror had passed away, I was immediately carried back into that state of heightened dread I associate with kid-like terror. Maybe all those possibilities are true somehow.

Much has been written about the impact of Romero’s low-budget approach, the sense of freedom it imparted to young directors then and since: fellow horror icon John Carpenter reflects that Night of the Living Dead “gave hope to those of us in film school that it was possible to make a low-budget movie and get it on the big screen.” And just as much has been written about the underlying race and class tensions that animate his best work.

This is all true. Romero paved the way for the whole notion of the midnight horror, the power of grainy images assembled and distributed by weirdos on the cheap, tapping into the zeitgeist.

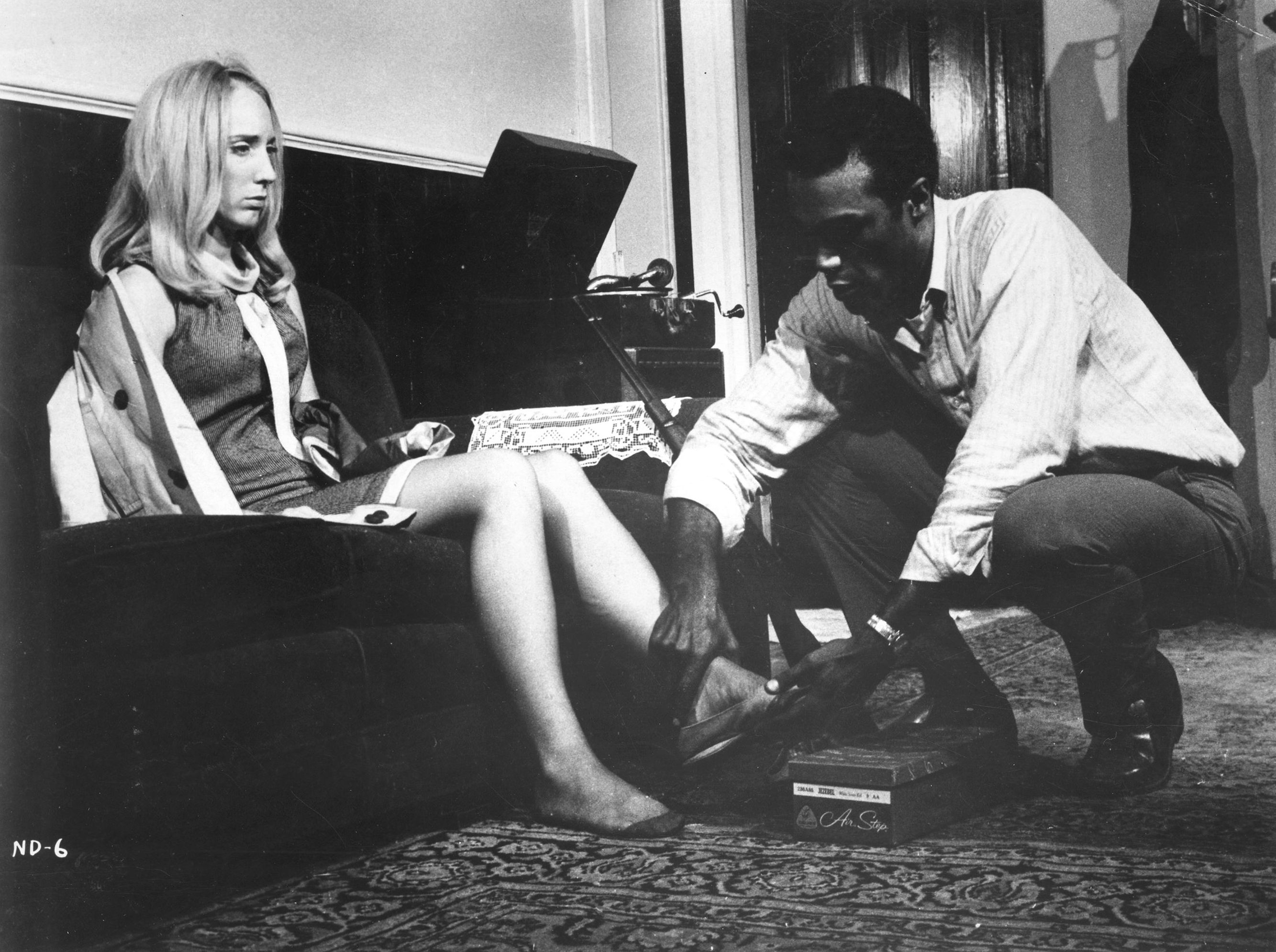

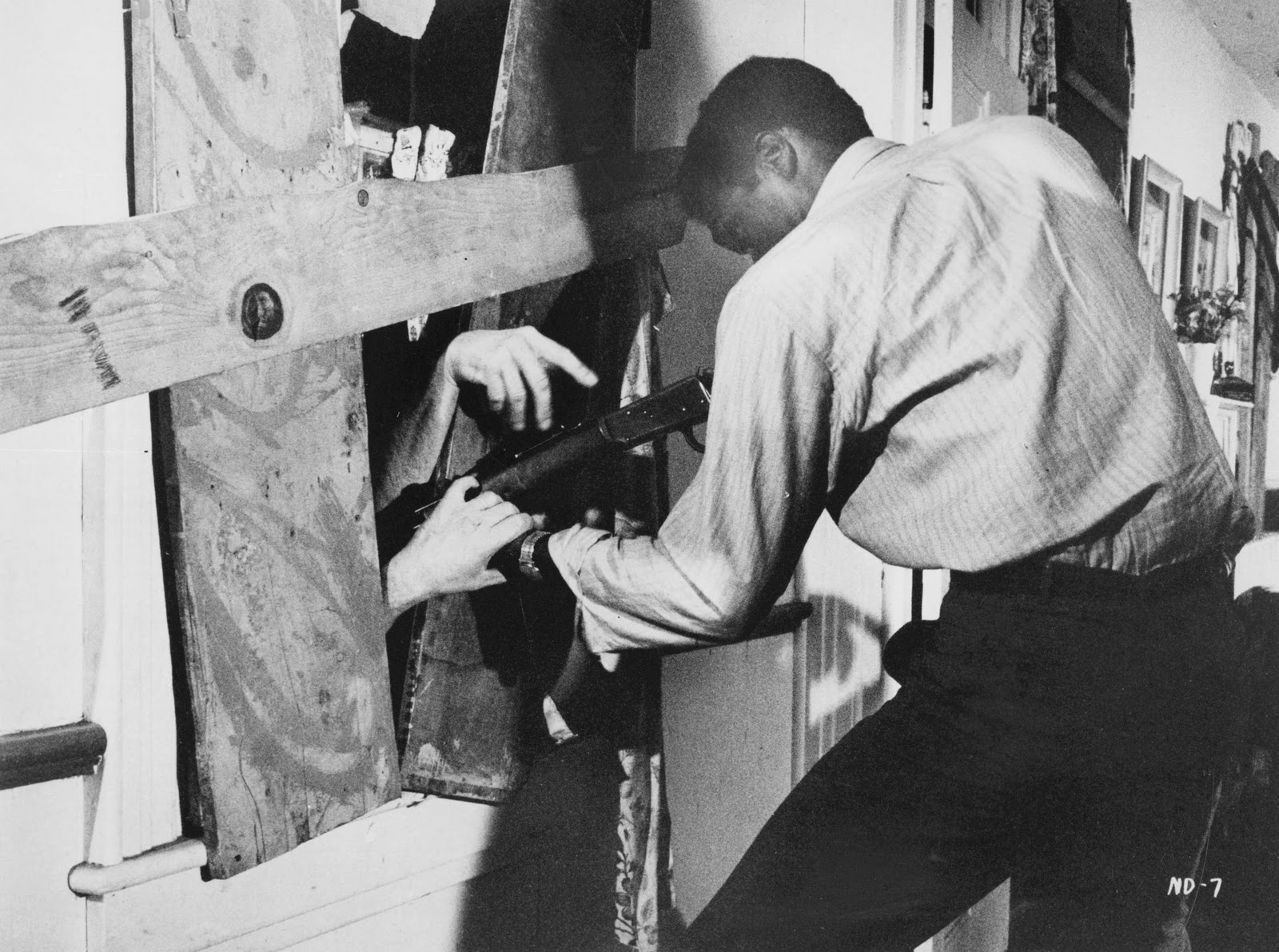

It’s also certainly correct that Night of the Living Dead centers race — via its protagonist Ben, the power struggles in a boarded-up house full of white people who fail to listen to him, and its climactic groups of redneck militias — in ways that still resonate.

Still, the lingering sense of the film, and a template for much of the best horror put on screen, is the way these subtexts arise organically from the material. Night of the Living Dead is incredibly sure of itself, its pacing and mood perfectly modulated to allow these subtextual meanings to bounce around without taking over the narrative itself. The lingering sense is overwhelming dread, processed, at least initially, like a child might. “The monsters are coming and they’re not going to stop.” Everything else comes later.

On rewatch, Romero’s deft touch becomes even clearer. The film’s first 10 minutes could be a standalone short just reveling in horror tropes: the radio foreshadowing, the Final Girl, the abandoned house. There’s an art-school sensibility at the start, a kind of fluttering, New Wave mood that Romero would put to devastating, more sustained use 10 years later in his under-celebrated piece of vampire melancholia Martin. Here, it’s a bait-and-switch, a promise of arthouse cinema promptly upended by splattering viscera and the literal claustrophobia of American life.

By more or less creating the zombie (a word never spoken in Night of the Living Dead), Romero assured his place in the horror pantheon. There’s a tendency to add to this a qualifier: “but he, and his films, are so much more than that.”

Well, they are and they aren’t. Romero himself liked to downplay the social contexts of genre, or at least his role in them, smiling and winking like a clever old man who knows he’s only half-right. (With his race-centering gore-fest premiering in Pittsburgh just 6 months after riots engulfed the city following Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, it’s doubtful Romero was completely oblivious to the subtext.)

The flipside of that qualifier is that downplays the real significance of the genre contribution. Romero infused his horror with social concern, whether by accident or design, but he also made incredibly tight, aesthetically accomplished horror movies, intelligent templates for others to explore and film experiences for many a young cinephile to treasure, even if he can’t exactly remember how the timing worked.

For a guy who liked to sign autographs with his admonition to “Stay Scared!”, that’s probably not a small matter.