Part of an ongoing effort to watch a set of films from non-White, non-U.S., non-male, and/or non-straight filmmakers and depart a little from the Western canon. The intro and full list can be found here.

Jean Cocteau rejected the label “Surrealist.” Contrary to notions of fundamentally unknowable art, born of dream and mining allusion, he began 1932’s Blood of a Poet with a title card that reads almost like a battle cry:

Every poem is a coat of arms.

It must be deciphered.

That’s pretty much a line in the sand, though Cocteau proceeds to complicate it every step of the way.

For all the surrealist (small s) touches, Blood of a Poet often plays more like a dance than story. It’s a balletic masterpiece, and not just because of the frequently stage-like movement. Neatly divided into four scenes depicting the infiltration of art into real life and the ways in which the artist grapples with it, it’s meticulous in its way. And although the words “dream-like” and “oneiric” appear in virtually every review, there’s a clear artistic, and intentional, drive behind all of it. This is a dream that knows it’s a dream.

There is some serious baddassery involved in this thing. To take one example. Cocteau — poet, dramatist, friend and/or lover to everyone in the early 20th c. avant-garde you’ve ever heard of — financed the film with borrowed money, and then featured his backers applauding a death scene he cut in later.

On the other hand, while Dali, Bunuel, or Man Ray’s approaches would seek to transcribe or represent impossible dream states, Cocteau had his feet on the ground. Shaky ground, sure, but ground nonetheless. Others might imagine someone waking up “through the looking glass”; Cocteau has his protagonist violently dive through a mirror into a shadow realm. It’s hallucinatory but also tactile and real.

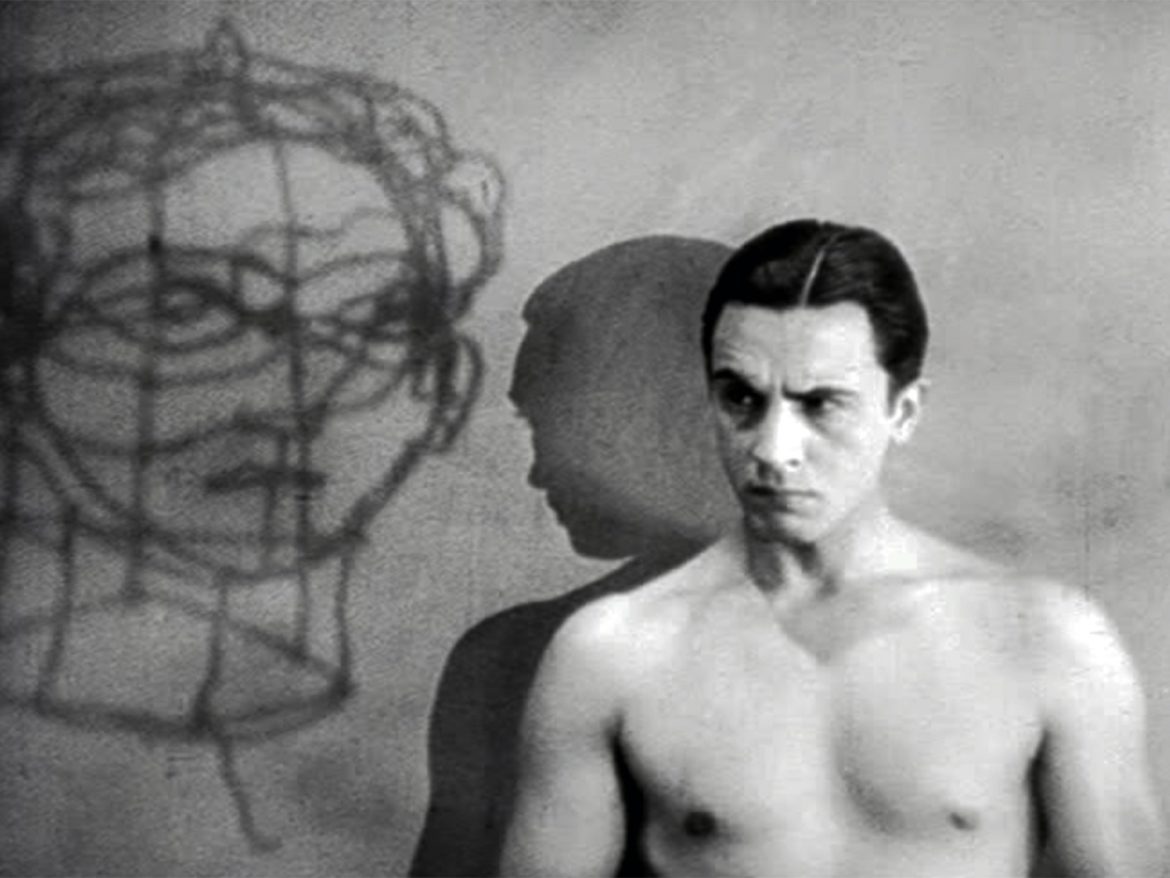

Blood of a Poet is basically about the struggle to create, both art and oneself. In the first section, an artist sketches a face, and its mouth becomes lodged in on his hand when he tries to rub it out — he and his art are joined, not very happily. In the second, desperate to escape, he jumps through a mirror into a hotel, where he watches people through keyholes, presumably gaining information about the world (and the world is very weird). Following the instructions of a statue come to life, he shoots himself in the head, and is reborn. But in a fury, he smashes the statue, his savior and creation. She’s reborn in section three, as shitty little kids throw snowballs at each other, turning increasingly violent, and using the poet’s frozen body as a weapon, along with rocks. Finally, his prone, bleeding body provides a foil in the last bit (titled “The Profanization of the Host”): as card sharks play for high stakes, his body hides an ace of spades, and a sexy (male) guardian angel comes to rescue him. We close with images of the lyre and a muse, looking back at us coyly as she departs.

There’s a lot of Cronenberg here, and Thomas Pynchon for that matter: In the second section, Cocteau had the floor painted to resemble the walls, so it disorientingly appears as though people are either flying or scurrying like particularly acrobatic insects. He called the segment “Learning To Fly”, after allowing us a view (through the protagonist’s keyhole peeping) at a woman whipping her child. Kinkiness and obscurity abound, and you get the distinct sense they are supposed to. Sex and violence are the baseline assumptions in this vision of the world.

As are visions of sacraments. Cocteau structures a world where desire and communion are linked to the uncanny — statues come alive, mouths breathe from hands, snowballs become marble, angels are objects of desire. His demand for interpretation becomes as ludicrous as the narrative.

The release of Blood of a Poet was delayed for years. Even in 1932, the Church, the censors, and the financiers were creeped out, at least a little.

Time has also proved them right. It’s an utterly scandalous film, adhering to mad logic that will never make sense, and, in its 55 minutes, filled with images any censor would deem “questionable.” God bless it for that.

Cocteau’s film is simultaneously a winking depiction of the terrors associated with creating any worthwhile art, and a lurid depiction of the weird things people might think along the way, and about as furious a bomb thrown from the back row as you’re likely to see.