Released in the closing days of the Silent Era, with production wrapping the same month The Jazz Singer premiered, Chaplin’s The Circus is a film that seems to know it’s aesthetic is on its way out the door.

Even with City Lights and Modern Times still to come, there’s an air of finality to it, perhaps most movingly encapsulated by its closing frames: we watch the circus leave the town and The Tramp behind, no better off than when he arrived to amuse the crowd at the start. Time and trends have passed him by.

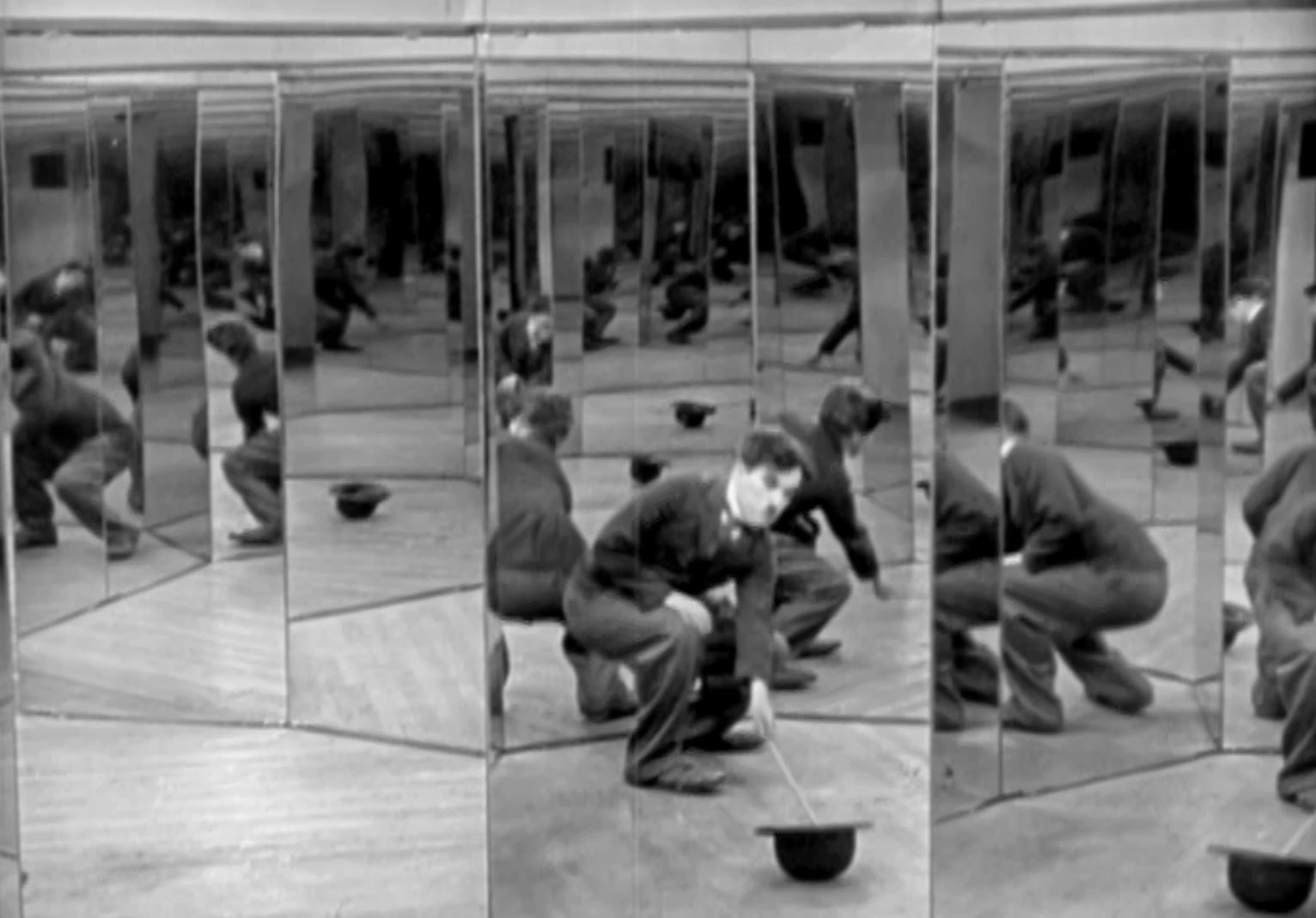

Less a coherent narrative than a loosely strung-together collection of gags, The Circus introduces love story conventions and triangles, set-pieces involving lions and tigers and monkeys (oh my), trapeze swinging and tightrope walking. One visually stunning sequence makes use of fun-house mirrors, and there’s meta-commentary to be mined from another one in which an old pie-throwing gag produces no new laughs. The Circus has a lot on its mind, and if it doesn’t all land, it boasts the benefit of something new to gawk at every minute.

The story, such as it is: mistaken for a pickpocket, Chaplin’s Tramp evades the cops at a fairground by accidentally running into, and ruining, a circus performance. As it turns out, however, the crowd loves him: as we’ll discover, this is only true when he doesn’t know he’s being funny.

He falls in love with a trapeze artist, but her affections are usurped by the debonair tightrope walker who joins the circus somewhat later. In an attempt to win her over, the Tramp takes his place on the tightrope, producing a several-minute-long, monkey-filled escapade that apparently took Chaplin over 700 takes to get right. At its conclusion, the Tramp, good guy to the end, realizes he can’t offer her much, blesses her union with his rival, and sees them off to further adventures down the road. He silly-walks the other way, back to the camera, into the distance.

That’s the gist, anyway. There’s also the mean-spirited circus-master (the girl’s wicked stepfather, conveniently enough), a hilarious attempt to forestall arrest by pretending to be an animatronic robot, several quick boots to the bum, and many things falling on everybody’s head all the time.

There’s vaudevillian virtuosity on display throughout The Circus, celebrated by audiences and critics at the time and since (it grossed $3.8 million, making it the 7th-highest grossing silent ever). But there’s also something else in its tone, an anger and a sadness.

The intertitles go out of their way to note that the tightrope, the spectacular medium of the Tramp’s victorious romantic rival, is a newfangled operation, contrasted with the music-hall comedy of old. “I don’t like tightrope walking,” Chaplin tells the Girl, before gleefully chuckling when it seems the man might fall. Other gags involve Chaplin beating up his boss, imagining himself beating up the tightrope walker, bonking people on the head, kicking clowns into barrels. For many of us, the defining characteristic of the Tramp character is his loopy sentimentality — in The Circus, there’s much more of an edge, bordering on the mean-spirited at times.

Does this issue from Chaplin’s awareness that the techniques he’d spent a career developing will be of limited appeal in sound cinema, the real-world corollary to the tightrope-walkers of the screen? Or perhaps the torturous circumstances of The Circus‘ production itself bled into the tone:

Chaplin was in the throes of the break-up of his marriage with Lita Grey; and production of The Circus coincided with one of the most unseemly and sensational divorces of twenties Hollywood, as Lita’s lawyers sought every means to ruin Chaplin’s career by smearing his reputation. At the height of the legal battle, production of The Circus was brought to a total halt for eight months, when the lawyers sought to seize the studio assets. Chaplin was forced to smuggle such of the film as was already shot to safe hiding.

Even before shooting began, the huge circus tent which provides the principal setting for the film was destroyed by gales. After four weeks of filming, Chaplin discovered that bad laboratory work had made everything already shot unusable. In the ninth month of shooting, a fire raged through the studio, destroying sets and props.

Later, when the unit returned to work after the enforced lay-off, they found that Hollywood’s mushroom real-estate development had in the meantime transformed the scenery beyond recognition. The troubles persisted to the very end. For the final scene, of The Circus moving out of town, the wagons were towed to location. When the unit returned for the second day’s shooting the whole circus train had vanished. It had been stolen by some high-spirited students who planned to use it for a marathon bonfire. This time, luckily, Chaplin was just in time to prevent the catastrophe.

That The Circus was completed at all now seems like something of a small miracle, and it does hold together in its loose-knit way, even if it lacks the coherence of some other Chaplin productions (to say nothing of the ambitious, now-troubling films of his compatriot Buster Keaton).

But the image that remains in my mind — apart from the Tramp seeming to be 30 feet up in the air, no visible net, balanced on a thin rope, performing an act he doesn’t know, with a monkey biting his face — is the film’s final one.

The wagons departed, the stage empty, he finds himself in the middle of the circle in the dust they’ve left behind. A closing iris shot isolates him as he skips away.

Something seems unmistakably over, and it’s not clear what’s ready to begin. It’s a melancholy note to end on, and it seems entirely appropriate.

It’s interesting to ponder how smart the Tramp really is, and how much he understands the situations he finds himself in. He’s sort of a Holy Fool. In “The Circus,” he gets hired as a clown by accident after he proves so incompetent as a property man that he steals the laughter from the real clowns. He’s the star of the circus, but has to have this explained to him by Merna, who plays the ringmaster’s mistreated stepdaughter. He has no idea what made him funny, no clear idea of why he stops being funny, and usually seems the unwitting pawn of events outside his comprehension.

This makes him, for me, a little less inspired than Buster Keaton, whose characters are smart and calculating, if also beset by life’s disappointments. But both get many of their laughs by their sheer physical grace and acrobatic skills. The physical world conspires against them, and they prevail. They are often yearning romantics, with this difference: Buster seems a plausible mate, and the Tramp hardly seems to possess a libido, only idealized notions. If their comedies had been made in a more liberated time, it is possible to imagine Keaton in bed with a woman, but disquieting to think of the Tramp as a sexual being.