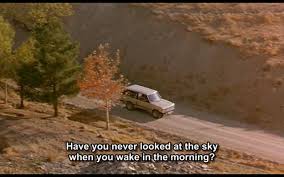

In Taste of Cherry, Abbas Kiarostami’s 1997 Palme d’Or winner at Cannes, we almost never stop moving. It is a film about a man whose life has crept to a halt, filmed in ceaseless motion.

There is almost no way to talk about Taste of Cherry, about its most resonant aspects, without what our generation has termed “spoilers.” There are spoilers here.

A spoiler-free narrative summary, almost entirely beside the point: Mr. Baadi is introduced behind a wheel, looking for someone, in a desolate hellscape of excavation outside Tehran, to help him with something. He drives his car around and meets people. Most are creeped out; others are unseen. His mission is opaque. Eventually, a Turkish guy, a taxidermist, can help. But he dislikes the idea. The film ends with a radical reversal of expectation. It’s heartbreaking and a spectacularly puzzling end to a narrative. It’s a narrative that devours itself.

Did that make things clear? No, it did not. But this is not an essay about the childish, festishistic demand for narrative innocence implied by “spoiler alerts”. Read on for details.

Mr. Baadi (Homayoun Ershadi) wants to die. We don’t know this right away, but we suspect it. The laborers who he passes in his car assume he wants either workers or sex. He wants neither.

He wants to be buried under a tree after he kills himself. Everyone he proposes this to is frightened. A shy, drafted soldier, a Kurd, flees as soon as hears. An Afghan security guard, standing watch alone over a region decimated by excavation trucks, won’t hear of it — he can’t leave his post, for one, and he has an omelette on the stove. A cleric-in-training agrees to take a ride in his care, but proceeds to lecture him about sin. Baadi is unmoved.

Only an unseen man, Mr. Bagheri (Abdolrahman Bagheri: note the name), takes him up on his offer. Baadi is offering substantial payment — he will take sleeping pills, you will make sure he’s dead, and you will throw some dirt on him. Not a bad day’s work. Bagheri accepts, to support a disabled daughter.

It’s a ripe narrative. And it’s not really what Taste of Cherry is about.

This is a film, so typical of Kiarostami, about the failures of communication, about the things that separate us from each other, and about the lure of images. Over and over again, obstructions block our view, or our hearing. “What was that?” is probably the most common refrain of the characters. We can’t see. We can’t hear. We can’t feel. We’re locked in, trying to claw our way out. Our notions of freedom are captive to structures we can’t control.

“What are you doing?” Badii asks some kids, rifling through the refuse. “We’re playing cars!” one responds, leaning out a window.

In one of the best scenes in Taste of Cherry, Badii stands in front of an excavation site, covererd in dirt while still standing. Someone asks him why he’s there, and he appears like he doesn’t know, or can’t explain. Bagheri later tells him a heartwarming story of how he once, too, considered suicide, but was rescued by the deliciousness of mulberries and the laughter of children. It seems a world far removed from the one we’re viewing. Here, kids play on slopes made of dust. The only cherry tree is the one Badii dreams of being buried beneath.

In its closing moments, Taste of Cherry revels in Kiarostami’s obsessions: artifice, illusion, the notion that images belong to those who find them. A blinking Badii, buried alive, witnesses a lightning storm, and we fade to black. It’s an arthouse ending, a pessimistic vision. “What happened?” you will ask. This is how arthouse films work. It is up to your discretion.

But not here. Instead, we cut from the stately film we’ve been witnessing to hyper-saturated video. Everything is blue and green. Ershadi emerges into the frame, a dead man from the grave. He lights a cigarette, and then walks up to Kiarostami himself, who is framing a scene. Someone yells out, “This is a sound take!” The soldiers, previously viewed only from a distance, are goofing off in the foreground.

What does it mean? Well, for one thing, that it’s a movie. That we cannot expect movies to replicate real life, that there is always intervention.

But in a larger sense, I think Taste of Cherry is about the ways in which we construct meaning. People try desperately to find them, and Kiarostami is acutely aware of this. But he’s also unwilling to be a liar. And that unwillingness to lie entails a desire to undermine the very images that construct truth.

It’s a hugely ambitious project, and it was his whole life’s work. We want the story to end, we want the man to choose one way or the other. We hope he chooses life, but we can’t be sure. Not until the final frame.

The final frame turns in on itself, and we discover we were watching a film. For Kiarostami, “the story” is about how stories don’t end. When that video comes on, and the dead man rises, we are aware that cinema is a lie, a metaphor. But, like Pynchon wrote, it’s a lie that aims at truth.

I’m tempted to call Taste of Cherry my favorite film of all time. But I just saw it for the first time; that would be hyperbolic. Kiarostami would giggle quietly at me, from behind sunglasses.

But it’s one of the truer things you will ever see. It knows exactly how we relate to images, and then proceeds to scramble the code.

It’s gorgeous and perfect, and, having only just discovered him, too late, I miss him a lot.