Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight For Freedom, the Netflix original just nominated for a best documentary Oscar last week, has two inescapable problems.

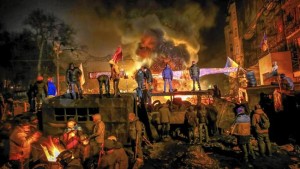

First, because the filmmakers are largely embedded with the Ukrainian resistance in 2013 and 2014 – and, understandably, because they want a narrative of heroic revolution that audiences can cheer – the film never really strays from a single set of viewpoints and experiences. Even the gripping riot sequences and the solidarity on display at Euromaidan – the name used to refer both to the central square in Kiev that Ukraine’s students, workers, and regular folks used much like the Egyptians at Tahrir, as well as their desire for closer ties to Europe rather than Russia – feel more like action movie set-pieces, complete with plucky youngsters fighting against all odds.

This is not to suggest that’s necessarily wrong – and definitely not to say director Evgeny Afineevsky should’ve interviewed the security forces brutally attacking protesters, much less sat down with Vladimir Putin, in a room I imagine is resplendent with bear-skin rugs and a series of pictures of himself fighting those bears while topless, to get his take on the whole thing. It’s just that, for the sake of immediacy, something is lost in terms of insight and, in some ways, accuracy.

Second, the film is necessarily partial in scope. There’s no way for a documentary chronicling a world historical event unfolding in real time to predict what will happen after the cameras stop rolling and the editing is complete. That’s a mundane and common issue for any “on-the-ground” depiction, but it’s pretty glaring here. The viewer is left energized by individual actors’ passion amid the outrageous violence of state forces, but also acutely aware that the story of Ukraine is far from over when the credits roll.

Taken on its own terms, though, Winter on Fire often succeeds enormously at its goals. There is no way to consider the people’s basic demands – that they want a say in how Ukraine positions itself to the world, that they want free and fair elections, an end to corruption and cronyism, and so forth – and the murderously authoritarian response to those demands with anything other than horror. The pitched street battles Afineevsky captures, and the offhand heroics of badly out-gunned dissidents, are indeed thrilling. It’s pretty hard to argue that things like AutoMaiden – a contingent of cars that kept a moving perimeter around the encampment – and ingenious sets of barricades are anything but awesome and inspiring. The film wants its audience wowed, outraged, and hopeful in the prospects for people-power. Mission(s) mostly accomplished.

But here’s where the two looming problems come racing back.

Despite the film’s single-minded commitment to portraying no one but heroes among the protesters, we now know that neo-fascist white supremacists played a not insignificant role in the events being portrayed. The Azov Battalion, for instance, made this very clear, expressly associating the Ukrainian struggle with leading “the White Races of the world in a final crusade for their survival.”

Not just that, but this wing, often at the forefront of skirmishes, received US training and financial support – an amendment to the federal budget prohibiting arming and funding neo-Nazi militants was actually stripped out of the final version, as The Nation reported (as it happens, on the same day Academy Award nominations were released). Your enemy’s enemy, and all that. By most accounts, groups like these were the exception rather than the rule, though the explicitly fascist Svoboda party ”won 10 percent of the vote in Kiev and placed second in Lviv [and its] candidate actually won the mayoral election in the city of Konotop” last October. These are not things you will learn from Winter on Fire.

As for scope, the film only mentions Russia’s annexation of Crimea in a footnote at the end, and provides little in the way of wider insight into the enormous regional clusterfuck. In some ways, this is not the filmmakers’ fault: your movie has to end somewhere, and you craft narrative with the footage you’ve got. But even leaving aside the practicalities, that’s a pretty big omission. You would be forgiven for thinking that the revolution succeeded without fail or setback and that Ukraine is now a peaceful democratic and egalitarian utopia, thanks to the efforts Winter on Fire depicts. That’s … not quite true.

I get it: capturing the world as it happens is extremely difficult and morally fraught, and Winter on Fire aims more to present a moment in time than deep political analysis. But for all the shock and exhilaration of its best sequences, the film still feels slight in the end, and incomplete.