No one told me about Yılmaz Güney, and I find this extremely rude.

Sure, I could’ve discovered one of the most famous figures of Turkish cinema on my own. It probably wouldn’t have been too difficult to uncover “the most seismic and controversial cultural figure of his generation and a catalyst for a new era of politically engaged filmmaking,” in Bilge Ebiri’s description, a writer and director who “remains an icon in Turkey to this day, his face gracing posters in coffeehouses and theaters, his name regularly invoked by contemporary filmmakers.” But would it have killed you to bring him up, given that he’s apparently the most interesting person in the world?

Here is a guy who was born to a Kurdish mother and a Zaza Kurd father, itinerant cotton workers who emigrated to Southern Turkey; Güney’s “career in cinema began in 1953 when he took a job with a film distributor touring prints nationwide.” (Later, by way of convincing him to return to filmmaking, he’d tell director Lütfi Akad, “I fed myself on your movies.” Güney meant this literally: “I slept on top of the boxes holding the reels.”) He’d serve his first prison term of many for writing a story identified by censors as “communist” (perhaps a percursor to later films exhibiting a broad sympathy to the disenfranchised). He rose through the ranks of Turkish cinema: first, as a star in a rush of genre movies — modeling himself after Cagney and Bogart and earning him the moniker “Ugly King” — and then as a director and screenwriter.

Imprisoned again for a week following the 1971 coup, he fled Ankara to make a film in Anatolia, and then was rearrested a year later, amid 1972’s widespread crackdown on leftists and sympathizers, for harboring anarchist student radicals. This unrest also included the executions of Deniz Gezmis, Yusuf Aslan, and Huseyin Inan of the People’s Liberation Army of Turkey (THKO), Marxist urban guerillas who’d carried out a string of actions of the “propaganda of the deed” variety. (Gezmis’ last words: “Long live a fully independent Turkey. Long live the great ideology of Marxism-Leninism. Long live the Turkish and Kurdish peoples’ fight for independence. Damned be imperialism. Long live the workers and the villagers.” Where this guy’s biopic?)

Imprisoned again for a week following the 1971 coup, he fled Ankara to make a film in Anatolia, and then was rearrested a year later, amid 1972’s widespread crackdown on leftists and sympathizers, for harboring anarchist student radicals. This unrest also included the executions of Deniz Gezmis, Yusuf Aslan, and Huseyin Inan of the People’s Liberation Army of Turkey (THKO), Marxist urban guerillas who’d carried out a string of actions of the “propaganda of the deed” variety. (Gezmis’ last words: “Long live a fully independent Turkey. Long live the great ideology of Marxism-Leninism. Long live the Turkish and Kurdish peoples’ fight for independence. Damned be imperialism. Long live the workers and the villagers.” Where this guy’s biopic?)

Released after a two-year stint, Güney promptly killed a right wing judge under disputed circumstances (he maintained his innocence), and was handed down a 19-year sentence. He cranked out screenplay after screenplay from behind bars which, though directed by others, still bore his authorial mark. (In fact, he seized on the conditions of their production to make a political claim, echoing the Dziga Vertov Group and others: “[P]ointing out,” according to the Harvard Film Archive, “that filmmaking is always a collaborative process, Güney declared himself deeply satisfied with these films.”)

In 1981, Güney didn’t so much “escape” as simply walk out of prison. If imprisonment was meant to diminish his fame, this hadn’t worked out at all, and he claimed, with some support, that the Turkish authorities preferred him exiled to jailed at this point. Still, he was officially persona non grata and fled, making films the whole time, including his most internationally celebrated one. As The New York Times succinctly put it, Güney “directed ‘Yol‘ from his cell in a Turkish prison and then escaped to edit the movie and see it win top honors at the 1982 Cannes Film Festival.” Güney was dead two years later of stomach cancer. He was 47 years old.

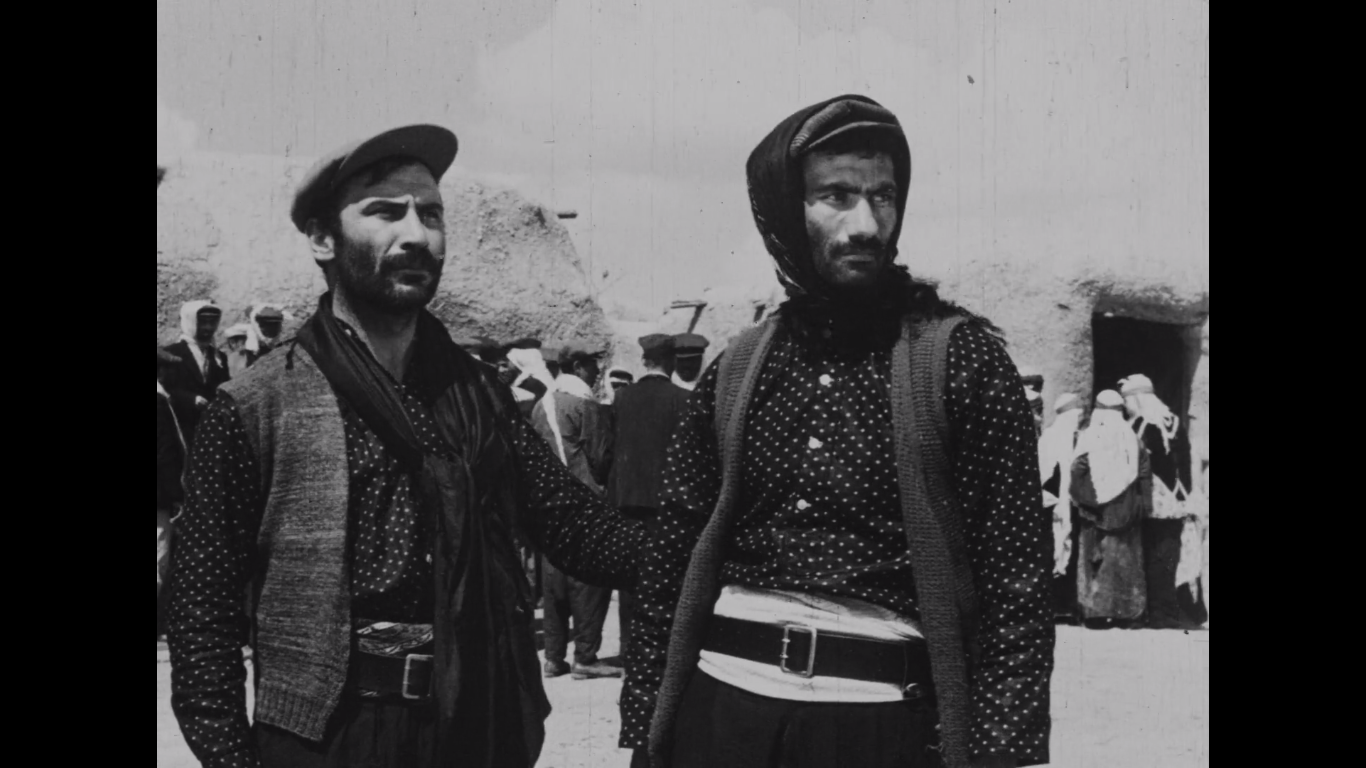

That’s a hell of a story, so why the relative invisibility? It may have something to do with the fact that Güney was largely erased even from Turkish cinema history until the early 80s. I only came across Güney in the course of my latest strategy for deciding on a movie to watch in the face of Streaming Paralysis: clicking Play semi-randomly on films I don’t know on Filmstruck, sorted alphabetically by director. In this case, it was Akad’s Law of the Border, a nearly-lost 1966 Turkish “western” (there are horses, anyway) in which Güney plays Hidir, a stoic bandit-type who shares more with Eastwood than Cagney.

That’s a hell of a story, so why the relative invisibility? It may have something to do with the fact that Güney was largely erased even from Turkish cinema history until the early 80s. I only came across Güney in the course of my latest strategy for deciding on a movie to watch in the face of Streaming Paralysis: clicking Play semi-randomly on films I don’t know on Filmstruck, sorted alphabetically by director. In this case, it was Akad’s Law of the Border, a nearly-lost 1966 Turkish “western” (there are horses, anyway) in which Güney plays Hidir, a stoic bandit-type who shares more with Eastwood than Cagney.

Law of the Border is the kind of film that begs to be described as “elemental”. It fits: it’s all white rock-and-sand expanses, lonely figures against unforgiving backdrops, furtive hiding and tense shootouts. It’s terrific. Akad makes wonderful, understated but deft use of the specifically Turkish architectural elements (one gun-toting chase through narrow alleys and unexpected archways stands out), and the script — Güney’s, stripped down by Akad to, well, its elements — is shot through with empathy for the villagers, scorn for the land-baron, and a sense of moral fable. (The central plot — about efforts to smuggle sheep across barbed-wire borders — shares more than a little with anti-capitalist, trans-national noirs like Anthony Mann’s Border Incident.) Güney carries entire scenes without a word, silently drawing all the attention to himself even as others jabber away and gesticulate. A sub-plot involving the creation of the village’s first school is a resonant tweak on themes of civilization and the badlands, while also tying in the hopes of Güney”s character for his young son, an ambivalent attitude toward citified salvational figures, and more.

All in all, I’m left wondering why it took so long for me to find Güney, hiding in plain sight amid the endless digital options, but I’m glad I did. This semi-random, alphabetical Filmstruck method is unlikely to become yet another Luddite Robot feature, but it’s almost certainly going to stay in regular rotation in my house. Though, if you’re wondering about pre- and post-Akad options: Valentina Agostinis‘ Blow Up of Blow-Up was enjoyable enough for Antonioni fans, and Chantal Akerman‘s Saute Ma Ville is like a looking-glass Jeanne Dielman by way of Daisies. The rest you’ll have to find out for yourself, and Turkish westerns starring judge-killing (allegedly), anarchist-harboring (definitely) fugitive filmmakers are a pretty solid place to start.