Like most movie enthusiasts, we watch more films than we ever have time or occasion to single out for longer, more in-depth discussion. Rather than cobbling together, as we have in the past, lists of currently streaming titles — there are plenty of astute critics already doing a wonderful job at this uniquely pain-in-the-ass endeavor — we’ve decided to just assemble some highlights from our week.

What Did You Watch This Week? Liz’s Highlights

Hard Rain (1998): There is no getting around it: I have a weird affection for the 90s thriller I can’t explain. Something about the shooting, the performances, the lighting — which is, objectively, terrible — just speaks to me on some level. So when you show me the pile of bad reviews for Hard Rain, I won’t disagree, but the simple fact is: I really like this dumb movie. The Hurricane Heist avant l’ouragan, it stars Christian Slater as an unlucky armored car security guard whose car is held up. The only wrinkle is, it’s held up in the middle of a city at the base of a dam, and as such it regularly floods to a depth dependent on the plot. It’s a goofy movie (although the third act twist legitimately caught me off-guard) that mixes disaster and heist loosely — and stars Morgan Freeman as a villain, for a change. But what really sticks out is the same thing that sticks with me from movies like The Poseidon Adventure: those strange moments where rising water levels change the way we treat the dimensions of the world around us, like in a thrilling prison cell escape or in the wonderfully strange scene where the robbers drive jet skis through a high school.

Hard Rain (1998): There is no getting around it: I have a weird affection for the 90s thriller I can’t explain. Something about the shooting, the performances, the lighting — which is, objectively, terrible — just speaks to me on some level. So when you show me the pile of bad reviews for Hard Rain, I won’t disagree, but the simple fact is: I really like this dumb movie. The Hurricane Heist avant l’ouragan, it stars Christian Slater as an unlucky armored car security guard whose car is held up. The only wrinkle is, it’s held up in the middle of a city at the base of a dam, and as such it regularly floods to a depth dependent on the plot. It’s a goofy movie (although the third act twist legitimately caught me off-guard) that mixes disaster and heist loosely — and stars Morgan Freeman as a villain, for a change. But what really sticks out is the same thing that sticks with me from movies like The Poseidon Adventure: those strange moments where rising water levels change the way we treat the dimensions of the world around us, like in a thrilling prison cell escape or in the wonderfully strange scene where the robbers drive jet skis through a high school.

The Murderer Lives at Number 21 (1942): We stand on the precipitous brink of a Clouzonaissance, in which we will finally appreciate the great French director Henri-Georges Clouzot. Clouzot is one of the handful of directors referred to as the “French Hitchcock,” but if so the case is better made by films like Les Diaboliques than the delightful The Murderer Lives. The Murderer Lives is more like a French version of The Thin Man, but one in which Nora is truly the equal her cultural prestige has led her to be; Suzy Delair, as the girlfriend who vows to solve the string of serial killings before her detective husband, gives a hoot of a performance. If Clouzot truly is the French Hitchcock, it comes with a shift in tone: Clouzot is far better at comedy than Hitchcock because, as a Frenchman, he can say those things to which the repressed Hitch could only allude, which naturally turns psychodrama into comedy. The final reveal may not be too surprising, but it is too legitimately funny to care.

The Murderer Lives at Number 21 (1942): We stand on the precipitous brink of a Clouzonaissance, in which we will finally appreciate the great French director Henri-Georges Clouzot. Clouzot is one of the handful of directors referred to as the “French Hitchcock,” but if so the case is better made by films like Les Diaboliques than the delightful The Murderer Lives. The Murderer Lives is more like a French version of The Thin Man, but one in which Nora is truly the equal her cultural prestige has led her to be; Suzy Delair, as the girlfriend who vows to solve the string of serial killings before her detective husband, gives a hoot of a performance. If Clouzot truly is the French Hitchcock, it comes with a shift in tone: Clouzot is far better at comedy than Hitchcock because, as a Frenchman, he can say those things to which the repressed Hitch could only allude, which naturally turns psychodrama into comedy. The final reveal may not be too surprising, but it is too legitimately funny to care.

Poor Little Rich Girl (1965): Andy Warhol was truly, in the most complete sense, a conceptual artist. It would be easy to do something like Borges, and, when he came up with a clever idea for a piece, put something together that gives the consumer the idea of the piece, and not bother to make the thing itself. Instead, Warhol followed his concepts to the absolute finishing point, for better (Poor Little Rich Girl) or for worse (the dull-as-dishwater Blood for Dracula and Flesh for Frankenstein). The idea for Rich Girl came partway through production: after filming a reel of Edie Sedgwick lounging around her house, improving the extremely loose plot of the film, they realized they had shot it out of focus. Instead of reshooting it, they simply shot another reel of footage, fully in focus, a move that can almost change how you look at women on camera. Suddenly, halfway through the hour-long film, after trying to track shapes across a film seemingly shot through a cataract, Sedgwick pops into perfect focus and we see her in her self-consciously draggy makeup, giving a strange performance that we now retroject into the film from the beginning. It’s a fascinating idea and one worth seeing — although, like all experimental films, seeing it in a real theater is a crapshoot; the bros behind me chortled the whole time as I wished death upon them.

Poor Little Rich Girl (1965): Andy Warhol was truly, in the most complete sense, a conceptual artist. It would be easy to do something like Borges, and, when he came up with a clever idea for a piece, put something together that gives the consumer the idea of the piece, and not bother to make the thing itself. Instead, Warhol followed his concepts to the absolute finishing point, for better (Poor Little Rich Girl) or for worse (the dull-as-dishwater Blood for Dracula and Flesh for Frankenstein). The idea for Rich Girl came partway through production: after filming a reel of Edie Sedgwick lounging around her house, improving the extremely loose plot of the film, they realized they had shot it out of focus. Instead of reshooting it, they simply shot another reel of footage, fully in focus, a move that can almost change how you look at women on camera. Suddenly, halfway through the hour-long film, after trying to track shapes across a film seemingly shot through a cataract, Sedgwick pops into perfect focus and we see her in her self-consciously draggy makeup, giving a strange performance that we now retroject into the film from the beginning. It’s a fascinating idea and one worth seeing — although, like all experimental films, seeing it in a real theater is a crapshoot; the bros behind me chortled the whole time as I wished death upon them.

What Did You Watch This Week? Rick’s Highlights

Body and Soul (1947): John Garfield‘s first collaboration with writer (and future Hollywood Ten member) Abraham Polonsky, who would direct him in the superior Force of Evil, one of the greatest of all noirs, the following year. Body and Soul has plenty to recommend it too, though: Garfield is excellent as the working-class boy rocketing to dubious success, the script sizzles despite being a bit overstuffed, and master cinematographer James Wong Howe casts his trademark pall over everything; even the light moments seem suffused with danger. (He also insisted on filming inside the ring, purportedly on roller skates, setting a template that every other boxing movie – including its most obvious descendant, Raging Bull – would strive to emulate). That Body and Soul is first and foremost a genre pic — rigged fights, the lures of crooked promoters, family and romantic melodramas — allows Polonsky ample oppotunity to sneak plenty of anti-capitalist strains into the Hollywood machine, including perhaps its most succinct, bitter summation, a bomb thrown from within by “a very dangerous citizen” who would be mercilessly targeted by the state in the years to come for his refusal to apologize, much less name names: “Everything is addition and subtraction. The rest is conversation.”

Body and Soul (1947): John Garfield‘s first collaboration with writer (and future Hollywood Ten member) Abraham Polonsky, who would direct him in the superior Force of Evil, one of the greatest of all noirs, the following year. Body and Soul has plenty to recommend it too, though: Garfield is excellent as the working-class boy rocketing to dubious success, the script sizzles despite being a bit overstuffed, and master cinematographer James Wong Howe casts his trademark pall over everything; even the light moments seem suffused with danger. (He also insisted on filming inside the ring, purportedly on roller skates, setting a template that every other boxing movie – including its most obvious descendant, Raging Bull – would strive to emulate). That Body and Soul is first and foremost a genre pic — rigged fights, the lures of crooked promoters, family and romantic melodramas — allows Polonsky ample oppotunity to sneak plenty of anti-capitalist strains into the Hollywood machine, including perhaps its most succinct, bitter summation, a bomb thrown from within by “a very dangerous citizen” who would be mercilessly targeted by the state in the years to come for his refusal to apologize, much less name names: “Everything is addition and subtraction. The rest is conversation.”

High Sierra (1941): The best thing about this nasty crime film is its obliviousness to its own content. Raoul Walsh, working from a John Huston script, seems convinced that this is a film about Bogart‘s Roy Earle, a one-last-job pro headed for a reckoning born of hubris and self-delusion. Bogart obviously seems to think so, and the film itself proceeds as though it were the case. But the structure of the narrative, and especially its Code-required third-act death, makes clear that this is entirely Ida Lupino‘s film. Her ex-dancing girl Marie — “a character trapped by the revolving door of double standards that plague countless women like her,” in Kristen Lopez’s formulation — is the one who undergoes an ambiguous transformation in High Sierra, she’s the one to whom we relate most intensely, and she’s the moral center of the grim proceedings, despite literally and figuratively being cast to the margins. It’s a fascinating case study in the way texts can elude their authors, as well as a tribute to the sheer force of intelligence in Lupino’s screen presence.

High Sierra (1941): The best thing about this nasty crime film is its obliviousness to its own content. Raoul Walsh, working from a John Huston script, seems convinced that this is a film about Bogart‘s Roy Earle, a one-last-job pro headed for a reckoning born of hubris and self-delusion. Bogart obviously seems to think so, and the film itself proceeds as though it were the case. But the structure of the narrative, and especially its Code-required third-act death, makes clear that this is entirely Ida Lupino‘s film. Her ex-dancing girl Marie — “a character trapped by the revolving door of double standards that plague countless women like her,” in Kristen Lopez’s formulation — is the one who undergoes an ambiguous transformation in High Sierra, she’s the one to whom we relate most intensely, and she’s the moral center of the grim proceedings, despite literally and figuratively being cast to the margins. It’s a fascinating case study in the way texts can elude their authors, as well as a tribute to the sheer force of intelligence in Lupino’s screen presence.

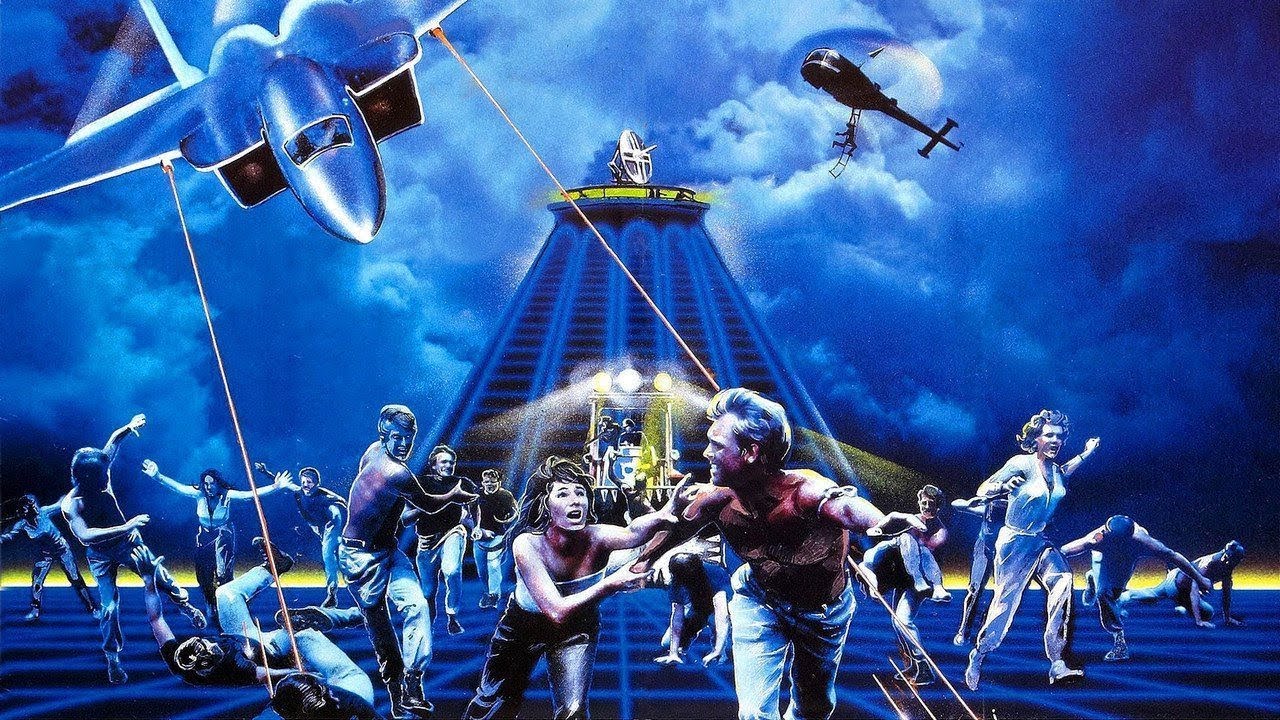

Turkey Shoot (1982): There have been many adaptations of The Most Dangerous Game, but this Ozploitation entry from Brian Trenchard-Smith (Dead End Drive-In, um, Leprechaun 4: In Space) is almost certainly the only one featuring a circus werewolf introduced wearing a top hat. Set in the kind of future dystopia that only a 28-day shooting schedule can produce, and starring the black hole of charisma that is Steve Railsback alongside Zefferelli’s Juliet Olivia Hussey, Turkey Shoot is, to put it gently, kind of a mess. But once the interminable first half is through clumsily establishing that future prison is future terrible, we are treated to 45 minutes of chase hijinks through Queensland and our Australian Z-movie folks doing what they do best, namely blowing shit up. Did I mention the werewolf? There’s also a werewolf. (Look for this on an upcoming episode of We Love To Watch, where Rick, Pete, and Aaron talk in more detail about Turkey Shoot than anyone involved in Turkey Shoot ever considered doing.)

Turkey Shoot (1982): There have been many adaptations of The Most Dangerous Game, but this Ozploitation entry from Brian Trenchard-Smith (Dead End Drive-In, um, Leprechaun 4: In Space) is almost certainly the only one featuring a circus werewolf introduced wearing a top hat. Set in the kind of future dystopia that only a 28-day shooting schedule can produce, and starring the black hole of charisma that is Steve Railsback alongside Zefferelli’s Juliet Olivia Hussey, Turkey Shoot is, to put it gently, kind of a mess. But once the interminable first half is through clumsily establishing that future prison is future terrible, we are treated to 45 minutes of chase hijinks through Queensland and our Australian Z-movie folks doing what they do best, namely blowing shit up. Did I mention the werewolf? There’s also a werewolf. (Look for this on an upcoming episode of We Love To Watch, where Rick, Pete, and Aaron talk in more detail about Turkey Shoot than anyone involved in Turkey Shoot ever considered doing.)