There are a lot of ways a filmmaker can be hard to like. They might make incredibly long films, or incredibly slow films, or incredibly slow, long films; they might be hard to track down, or hard to find in decent-looking formats; they might make wonderful films but be awful in real life. Michael Haneke doesn’t quite fit into any of those categories. (At least, I didn’t think he fit into the last one; his recent, incredibly dumb comments on #MeToo make him sound like a candidate.)

His movies aren’t fun, but they’re not really slow or particularly long, and after a few brushes with Oscar success, a lot of his movies are pretty easily accessed.

How do you identify the off-putting thing about Haneke’s movies? Is it that they’re dour? Sure, but there have been plenty of great dour filmmakers. Is it that he’s preachy? Sure, but most of the things he’s preaching against — racism and the casual cruelty of people with cultural power — are legitimately horrible.

How do you identify the off-putting thing about Haneke’s movies? Is it that they’re dour? Sure, but there have been plenty of great dour filmmakers. Is it that he’s preachy? Sure, but most of the things he’s preaching against — racism and the casual cruelty of people with cultural power — are legitimately horrible.

No one is better at depicting the quiet suffocation of modern life, but in his worst movies, like the two basically identical versions of Funny Games, that suffocation seems to leak from the screen into the theater. There is so little room for creative freedom on the part of the viewer that one wonders why one is even watching at all. (Which was the ultimate problem with Funny Games, a movie that openly tells the audience not to watch it.)

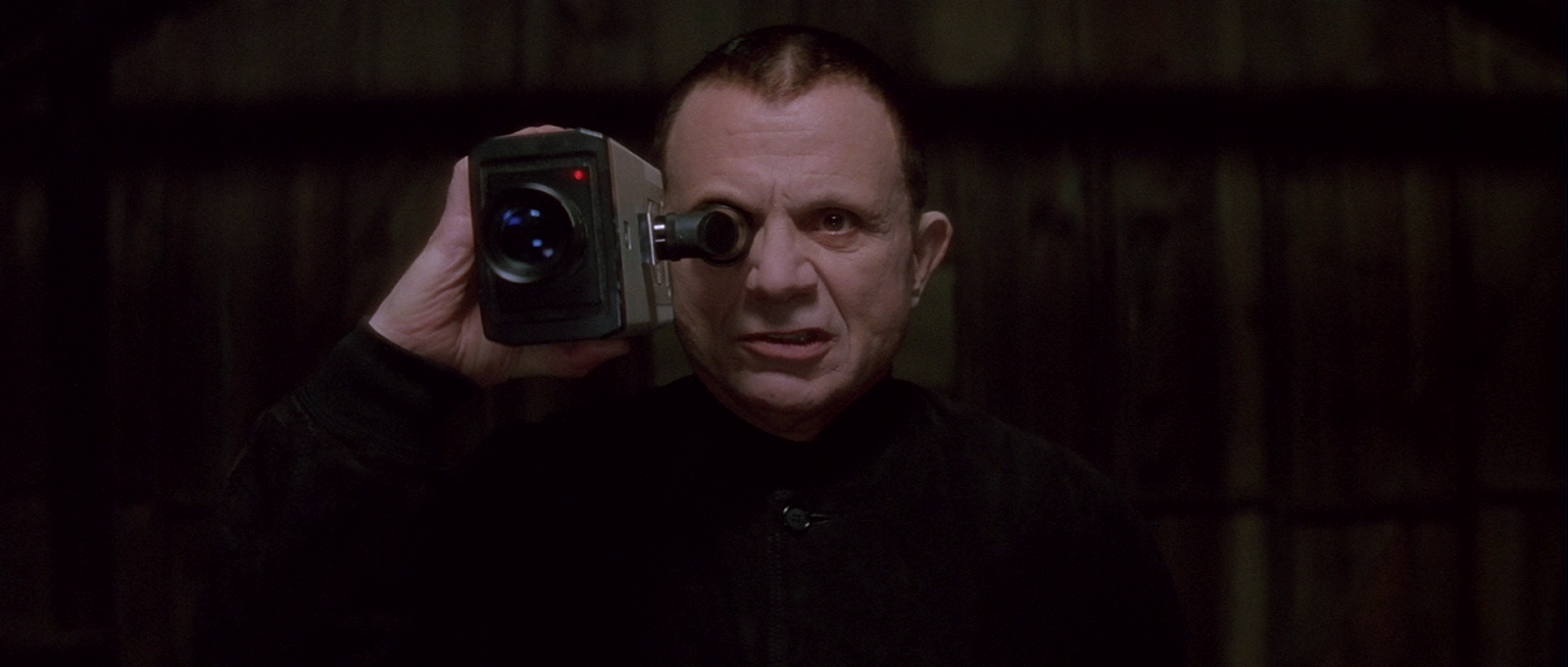

I’m not sure if 2005’s Caché is one of his films that escapes this sense of suffocation, or if it is simply one that uses it most effectively within its own context. The plot is basically identical to the first half of Lost Highway: a tense and highly-strung marriage is interrupted by a series of mysterious tapes left on their front porch.

I’m not sure if 2005’s Caché is one of his films that escapes this sense of suffocation, or if it is simply one that uses it most effectively within its own context. The plot is basically identical to the first half of Lost Highway: a tense and highly-strung marriage is interrupted by a series of mysterious tapes left on their front porch.

But where Lynch escapes into imagination, Haneke sticks with his surveilled couple. In Highway the motivating factor is a future-bound paranoia: the tapes move Bill Pullman inevitably towards the horrific murder of his wife. In Caché, the motivating factor is a past-bound guilt.

The husband (Daniel Auteuil, who I believe has never smiled in his life) is immediately convinced of the culprit: an Algerian orphan (Maurice Bénichou) who his parents almost took in as a child, but who Auteuil lied about and who was sent away to live a life of poverty.

In his previous attempts to address racism, Haneke had depicted the lives of immigrants, but any real exploration of bigotry from the side of the oppressed has to contrast the joy of life with the horror of its squelching, and Haneke simply does not seem to have the skill to present joy well. Instead, his oppressed figures are mostly objects of pity.

By placing Caché in a fantastic world, though, by presenting an impossible mystery — we know from the first shot that, despite Auteuil’s search for the culprit, the tapes could not be recorded by any real human — Haneke stops trying to guilt racism away and gives himself real space to explore the oppressor’s world.

By placing Caché in a fantastic world, though, by presenting an impossible mystery — we know from the first shot that, despite Auteuil’s search for the culprit, the tapes could not be recorded by any real human — Haneke stops trying to guilt racism away and gives himself real space to explore the oppressor’s world.

Caché is a movie about guilt, paralyzing guilt that multiplies harm exponentially. Because of his childish mistakes, Auteuil caused his almost-brother far more pain than he could have guessed. And his impossible need to deny what happened leads him to denying it pathologically instead of making restitution.

It’s never said outright, but the tapes seem almost to be a physical manifestation of Auteuil’s guilt. By holding onto the guilt of his sin, he manages to make Benichou’s life even worse.

All of this makes Caché one of Haneke’s most remarkable movies. But what does it in turn say about Haneke’s earlier works? The opening shot, a long static shot with credits overlain that turns out to be the first tape which the couple is watching, already blends the film itself and the videotapes within it.

All of this makes Caché one of Haneke’s most remarkable movies. But what does it in turn say about Haneke’s earlier works? The opening shot, a long static shot with credits overlain that turns out to be the first tape which the couple is watching, already blends the film itself and the videotapes within it.

If the tapes are a manifestation of Auteuil’s guilt, can’t one also say that Haneke’s early attempts to address racism are, in some way, manifestations of his guilt as a white Austrian? It’s this kind of secret doubleness that makes Haneke’s filmography more subtle and nuanced than their miserabilist front. It’s also hard to know how much of this is purposeful metacommentary and how much is not, but it is there either way. And it is problems like that that make Haneke hard to like.