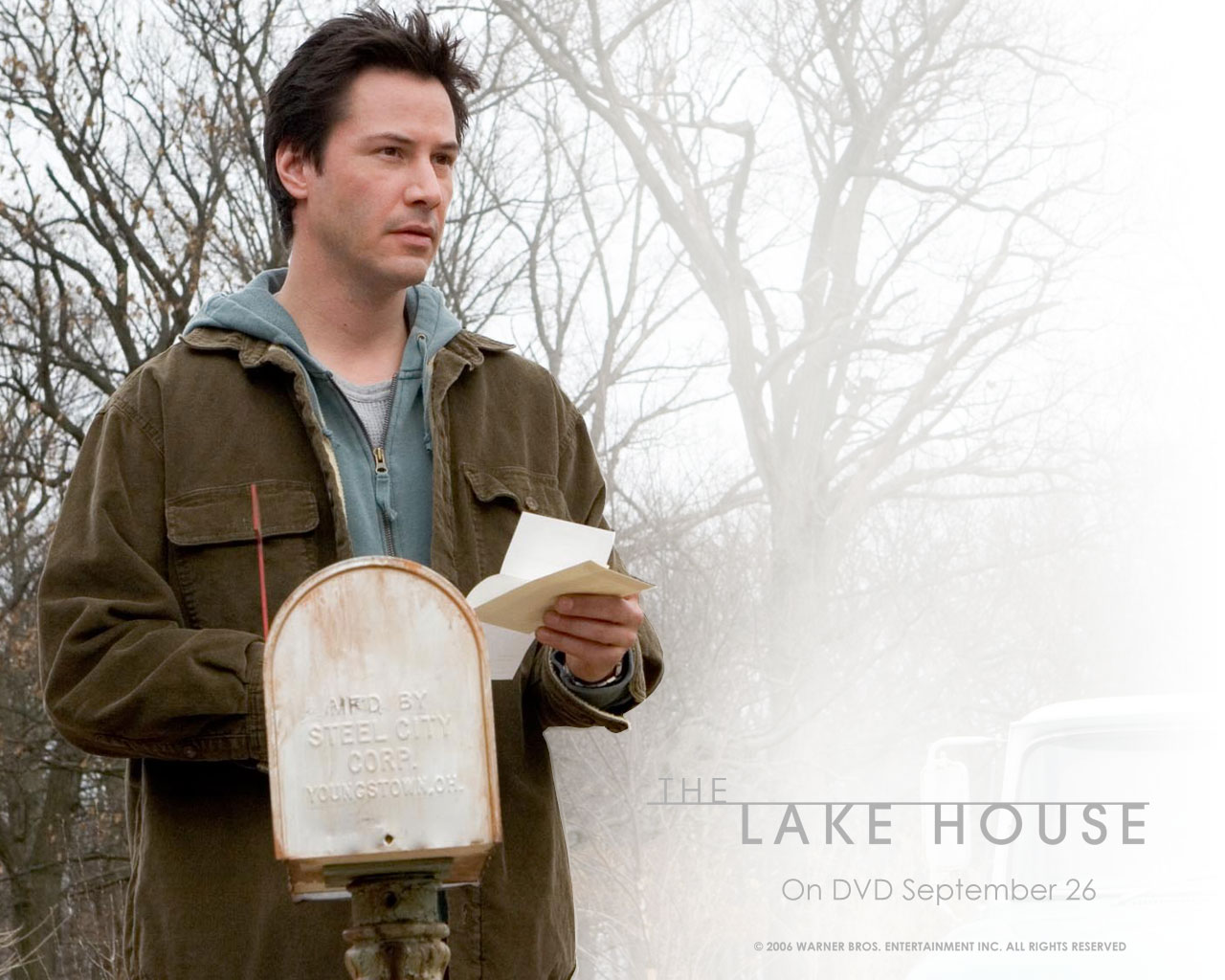

The premise of The Lake House — that two lonely singles, Keanu Reeves and Sandra Bullock, can fall in love by sending messages back and forth to one another through the time-travelling mailbox outside the home that they both, on different occasions, owned — opens itself up to two smart-ass questions, or maybe two smart-ass fields of questions. One relates to its romantic drama trappings, and the other to its time-travel trappings.

The first one is: How can we believe any of this? How do we know that 10 months after The Lake House ends, they won’t be broken up after one too many arguments about Keanu leaving his socks out?

I’ll leave aside the fact that these questions are usually asked from a position of pseudo-feminism, by men who have managed to find a way to demean anything consumed mostly by women in the name of defending them. Even ignoring the obviously shallow place these criticisms come from, they ignore what we all implicitly know about these romances.

These romances have nothing to do with relationships. This is not a world of relationships. At least one of the leads, if not both, come saddled with a relationship when the movie opens; in The Lake House, Bullock gets Dylan Walsh as her borderline-stalker “old partner” who was just too boring for her. (Walsh is, like many former boyfriends over the last couple decades, trying desperately to channel Bill Pullman.)

The philosopher Alain Badiou talks a lot about the “truth-event”, unpredictable and unforeseeable moments in life in which something completely new opens up, something that reorganizes how you look at life. It is to a person’s day-to-day life what a black hole opening up in a downtown, metropolitan area would be. Suddenly, everything has a new point towards which it must orient itself.

Badiou gives us four “orders” of events: science, politics, art, and love. It is this sense of love, not as a relationship but as an event, that these movies enact, and it is a desire for them that drives our emotional involvement. Romantic movies transcend mere romance. They speak to a desire to reorient everything.

But, of course, these movies don’t offer a real revolution, whatever that would mean. I’m not arguing that we should sit quietly and ignore the details of the films. The question is not “Is this relationship believable?” The question is, “How does the narrative manufacture this event of romance? What tricks does it use to make what should be a sudden surprise slowly inevitable?”

For While You Were Sleeping, the conceit that manufactured the romance was a subway accident; for Sleepless in Seattle, it’s Tom Hanks’ son calling in to the radio. For The Lake House, it’s more explicitly magical: the mailbox outside the two leads’ home, which sends messages between them.

This conceit opens up the second field of smart-ass questions, which goes something like this: How does the time travel work? Is it consistent? Are there any plot holes? If they could send messages, why didn’t they just do X, why didn’t they just invest in the stock market and make millions, why didn’t they stop random murders?

The demand for consistency is uniquely aimed against time-travel movies. I understand the urge: the rules usually seem clear, which leads the audience to try to figure out other ways that perfectly rational characters, according to a rather peculiar but mostly unquestioned definition, could solve their problems.

But the problem here is a lot like the problem with the romance questions. Time travel has a function beyond just being another way to complicate a plot. The driving need for romance in our lives, not defined as a particular type of relationship but as something electric and inexplicable, comes from a feeling that we must find love, that we must live life to the fullest.

One of the phrases associated with Kant’s ethics is “ought implies can”. If we ought to do something, then we must be able to do it; otherwise, it would not be reasonable to say we ought to do it. We are sent messages that we ought to live life to the fullest, but there’s no guarantee that we can do that. It may be we ought to fall in love, but it’s completely possible that it never happens to us.

Time-travelling protagonists and romantic protagonists both are offered a conceit, a narrative world, in which their response to these ethical injunctions can definitely be positive. The mailbox at the lake house, as both romantic and time-travelling conduit, is a guarantee of living life to the fullest. It reaches out and grabs them.

This is a very long preamble for an entire other essay, honestly. Because it is the specific semiotic form that that solution takes that gives the character to a romantic movie, comedy or drama. In the same way that what is interesting about a slasher movie is not the basic format but the trappings, the superfluous extras that try to cover up that structure, what is interesting about romantic movies is not the basic format but the form that that short circuiting, that guarantee of love and truth reaching out towards the protagonists, takes.

For an entire sub-genre of movies, it is something about writing, from The Notebook to You’ve Got Mail (and The Shop Around the Corner) to The Lake House. The semiotic system is the magic bullet that makes the world livable. I’m hoping to turn and write more about this soon, but if I don’t get a chance, keep this in mind when you watch a romantic movie: how is this movie trying to justify making “ought mean can”? What’s the system it establishes, the conceit it creates, to try to make that necessary?