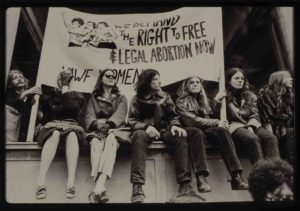

Watching She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry, director Mary Dore’s perfectly agreeable and accomplished 2014 documentary about the birth of the modern women’s movement in the U.S., it’s hard not to feel there’s something staid about the proceedings.

This is less the fault of the film itself than a reflection of how exciting the landscape of documentary film has become in recent years. There has been such a steady stream of formally daring and aesthetically interesting entries in the genre that good, old-fashioned expository docs can’t help but seem prosaic, with their array of talking heads in mid-shot, narrative-driving needle drops, and carefully curated archival footage.

This is less the fault of the film itself than a reflection of how exciting the landscape of documentary film has become in recent years. There has been such a steady stream of formally daring and aesthetically interesting entries in the genre that good, old-fashioned expository docs can’t help but seem prosaic, with their array of talking heads in mid-shot, narrative-driving needle drops, and carefully curated archival footage.

That’s not to say She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry is unnecessary or without important things to say – if anything, its discussions of concerted political attacks on women’s health, heroic examples of community self-help, the dangers of resistance movements replicating the power dynamics they assail, and the importance of intersectionality are more timely than ever. But the film’s aesthetic throws into sharp relief the innovations that have been taking place in the form.

Of course, multiple modes and narrative traditions of documentary film have co-existed for most of film history. From the early actualities and Flaherty’s Nanook of the North through Dziga Vertov’s montages, from avant-garde juxtapositions and more poetic treatments to journalistic approaches, pure propaganda, cinéma vérité and direct cinema – just to scratch the surface – a diversity of forms is nothing new.

But the last few years have seen a remarkable resurgence of experimentation, or at least a renewed mainstream attention to it. For a while, it seemed that things like Michael Moore’s performative interrogations and Errol Morris’ self-reflexive films (along with the more cult favorite status of someone like Ross McElwee) represented the only really viable alternative to what most of us probably think of as “the standard documentary.” Even a madman like Werner Herzog’s forays into documentaries, while consistently fascinating, have hewed pretty close to convention (though he’s been quick to deploy newer technical approaches and all are imbued with his characteristic weirdness).

More recently, however, Joshua Oppenheimer’s remarkable masterpiece The Act of Killing, and more conventional but still bracingly participatory The Look of Silence, represented a sudden, dramatic shift. (In fairness, Herzog and Morris were both involved as producers of Oppenheimer’s projects. But as far as institutional appeal, it’s worth noting that the first lost out at the Oscars to the crowd-pleasing 20 Feet From Stardom and the second to the heart-breaking Amy, both entirely worthy but more conventional choices.) Sarah Polley’s Stories We Tell, which saw the doubt inherent in the approach of someone like Morris and raised it substantially, represents another offshoot into new areas. Elsewhere, on a wall somewhere, Frederick Wiseman is still out there, doing his Frederick Wiseman thing.

More recently, however, Joshua Oppenheimer’s remarkable masterpiece The Act of Killing, and more conventional but still bracingly participatory The Look of Silence, represented a sudden, dramatic shift. (In fairness, Herzog and Morris were both involved as producers of Oppenheimer’s projects. But as far as institutional appeal, it’s worth noting that the first lost out at the Oscars to the crowd-pleasing 20 Feet From Stardom and the second to the heart-breaking Amy, both entirely worthy but more conventional choices.) Sarah Polley’s Stories We Tell, which saw the doubt inherent in the approach of someone like Morris and raised it substantially, represents another offshoot into new areas. Elsewhere, on a wall somewhere, Frederick Wiseman is still out there, doing his Frederick Wiseman thing.

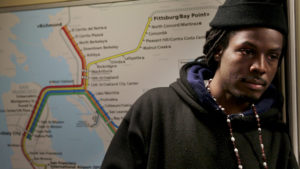

As it happens, my favorite films from the past two years at the San Francisco Film Festival were documentaries – Jason Zeldes’ Romeo Is Bleeding last year and Peter Middleton and James Spinney’s Notes On Blindness this time around. And, interestingly, both Zeldes and Middleton/Spinney have cited Oppenheimer and Polley as influences, in spirit if not necessarily in specific form. Romeo Is Bleeding blends numerous narrative and aesthetic strategies – in Zeldes’ words, “it’s vérité meets archival meets theater, dance, and poetry” – and Notes On Blindness seeks nothing less than the creation of an entirely new mode of filmic storytelling, one that grapples with the paradox of a cinema of blindness. Both are tremendously successful in different, unique ways.

As it happens, my favorite films from the past two years at the San Francisco Film Festival were documentaries – Jason Zeldes’ Romeo Is Bleeding last year and Peter Middleton and James Spinney’s Notes On Blindness this time around. And, interestingly, both Zeldes and Middleton/Spinney have cited Oppenheimer and Polley as influences, in spirit if not necessarily in specific form. Romeo Is Bleeding blends numerous narrative and aesthetic strategies – in Zeldes’ words, “it’s vérité meets archival meets theater, dance, and poetry” – and Notes On Blindness seeks nothing less than the creation of an entirely new mode of filmic storytelling, one that grapples with the paradox of a cinema of blindness. Both are tremendously successful in different, unique ways.

All of which makes me wonder if the traditional, expository form She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry takes is likely to become more the exception than the rule one day. There will always be a demand for well-told histories, and Dore’s film is certainly that: the interviews with 60s and 70s luminaries like Rita Mae Brown and Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz are full of wisdom, the archival footage (some of it provided by local SF heroes Oddball Films) still thrills, and, with the exception of some painfully unnecessary staged readings (ironically, the film’s only real attempt at mixing things up aesthetically), all of the pieces fit. The film also deserves bonus points for its frank airing of internal grievances, its emphasis on its subjects’ reappraisals of tactics in hindsight, and how far it goes out of its way to complicate the overwhelming whiteness of the movement’s founders, giving plenty of space to the Black and Brown feminists who forced their way into a discussion that didn’t seem to realize it was shutting them out.

All of which makes me wonder if the traditional, expository form She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry takes is likely to become more the exception than the rule one day. There will always be a demand for well-told histories, and Dore’s film is certainly that: the interviews with 60s and 70s luminaries like Rita Mae Brown and Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz are full of wisdom, the archival footage (some of it provided by local SF heroes Oddball Films) still thrills, and, with the exception of some painfully unnecessary staged readings (ironically, the film’s only real attempt at mixing things up aesthetically), all of the pieces fit. The film also deserves bonus points for its frank airing of internal grievances, its emphasis on its subjects’ reappraisals of tactics in hindsight, and how far it goes out of its way to complicate the overwhelming whiteness of the movement’s founders, giving plenty of space to the Black and Brown feminists who forced their way into a discussion that didn’t seem to realize it was shutting them out.

Or maybe this will remain the dominant approach. It may be that audiences will always prefer it to other, more challenging or jarring ones, and so, therefore, will those who bankroll documentary film. There’s something reassuring about its familiarity, as archival footage of a young person morphs into a contemporary interview, and name cards comfortingly locate us. We can’t get lost or lose our footing, even for a moment. We are in the capable hands of creative technicians with worthy stories to tell, in ways we recognize without hesitation.

Which is fine. None of this is to say that the archival approach is without merit, or that, somehow, archives themselves are of any diminished value. (Quite the opposite.) But the hopes for new insight in the documentary films to come lie more with the modes being explored by the Oppenheimers and Polleys – and the Zeldes’ , Middletons, and Spinneys – than they do in the discreet forms of the past we’ve come to know so well, which ably inform but fail to startle.