Recently, the good folks at Swampflix invited me onto their podcast to talk about the films of Richard Kelly: Donnie Darko, Southland Tales, and The Box. (I’m leaving aside Domino, because he did not direct it, and because it is both atypical, a Tony Scott film, and also bad.)

This invite may or may not have arrived because I, too, am named Richard Kelley, and therefore presumably have a unique insight into the mind of my doppelganger. (This would certainly make sense to Richard Kelly, I think.) But, instead, after several days spent in the weird, watery, alternate dimensions of his work, I have more questions than answers.

Among them: why is the cosmically baffling Southland Tales not considered a cult classic?

Donnie Darko is a perennial favorite for critics and freshman college students alike and The Box is Kelly’s secret masterpiece. But why hasn’t official cult status been conferred on Southland Tales? It seems to have everything it would require.

Sure, you could reply with the stock answer, “Because Southland Tales is bloated, incomprehensible, and not very good.” That would be fair, and it was certainly how it was received in 2006, at what Roger Ebert called “the most disastrous Cannes press screening since, yes, ‘The Brown Bunny’”.

It has its defenders these days, but it’s not exactly beloved. On Rotten Tomatoes, it stands at 36% for critics and a slightly more generous 41% from audiences, and while the Swampflix folks and I had positive things to say, our friends over at We Love To Watch were decidedly less enthusiastic.

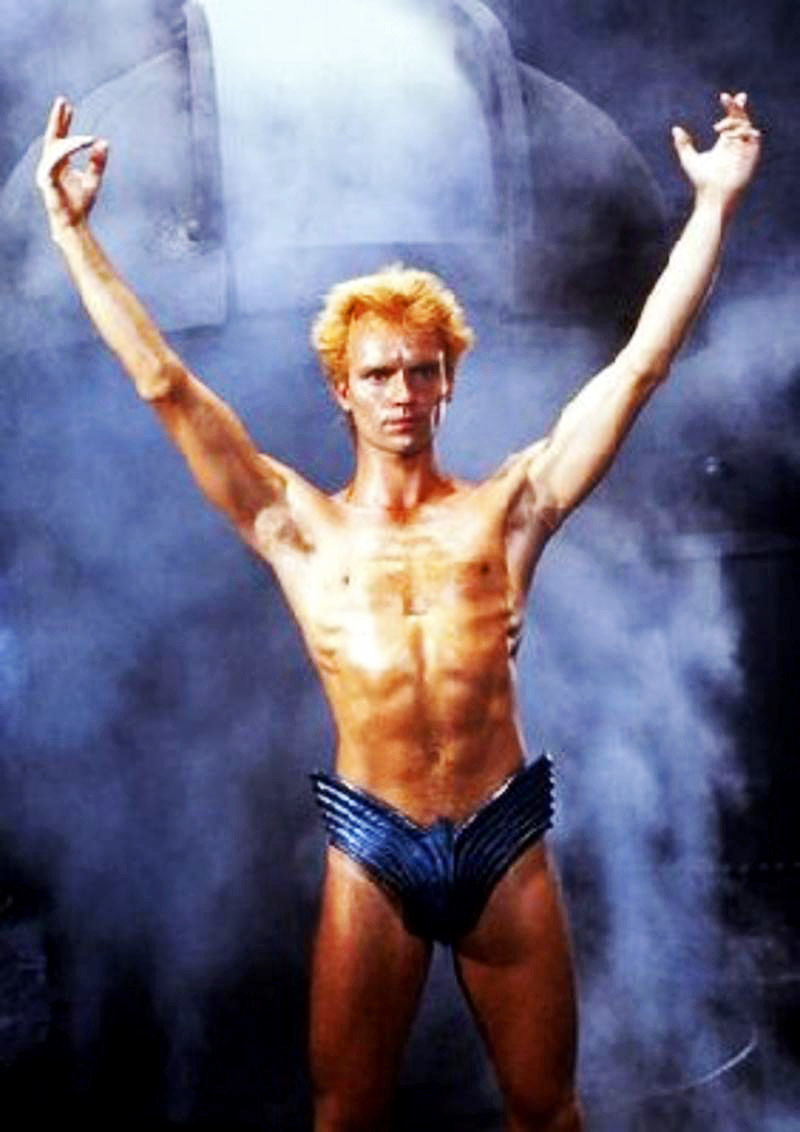

But an unfavorable, even disastrous reception and a clunky, overextended narrative doesn’t fully explain it. Poor box office is basically a requirement of the category. “Bloated and incomprehensible” certainly didn’t get in the way of recuperating David Lynch’s Dune as a cult materpiece for a significant chunk of viewers, some of whom now see in it the stamp of its auteurist creator where once people mostly just saw Sting in a Speedo from the future and Kyle Maclachlan saying things like, “Stilgar, do you have wormsign?”

This should seem to bode well, actually, for the ludicrously overextended, much-derided Southland Tales: Kelly is nothing if not peculiarly fixated on his pet themes and aesthetic, and his previous Donnie Darko is as good a candidate as any for the paradigm of the modern cult classic. (In fact, it’s Entry #1 in Scott Tobias’ series The New Cult Canon on the AV Club.) So why not his follow-up?

At least part of the answer lies with the question of intent. The films that end up embraced by a legion of die-hards are often issue from directors with a singular, sometimes dubious vision. This isn’t always true, but there are plenty of examples. The very same ambition that can produce a masterpiece can also produce something so wildly misjudged that it becomes lovable for that very reason. You can tell where it was supposed to land, but something went kind of wacky along the way.

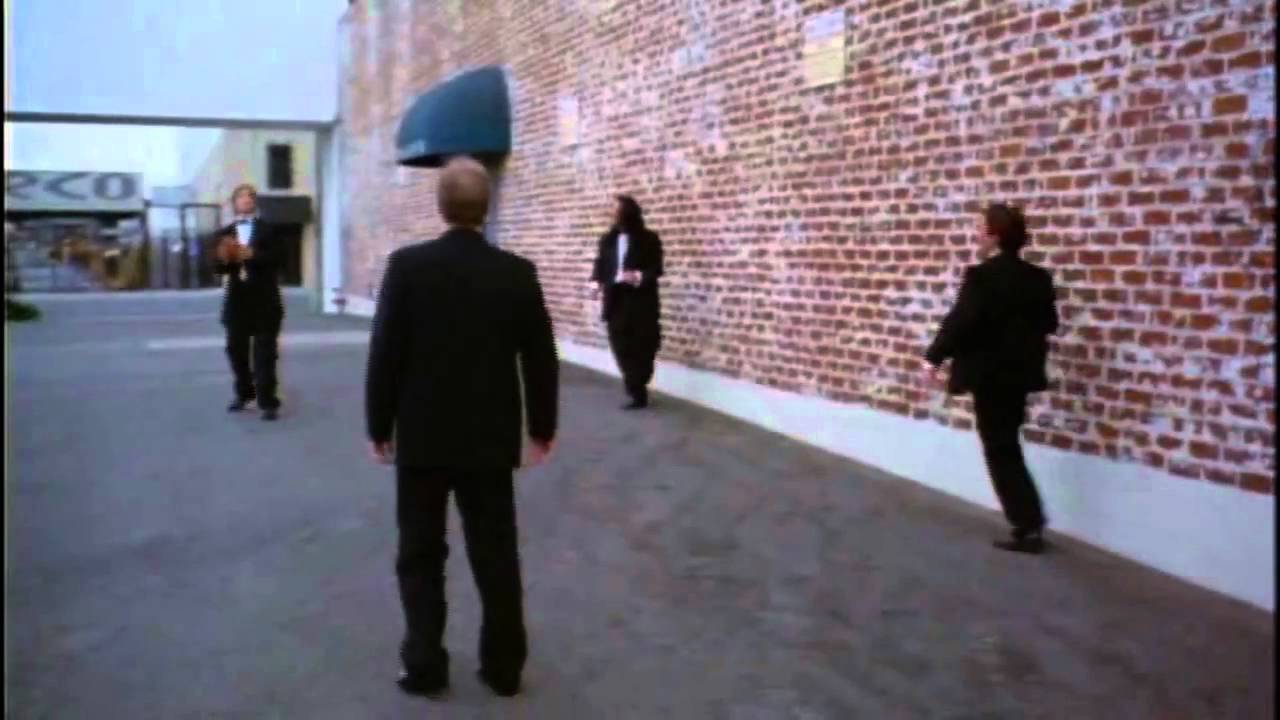

To take one recent example: audiences continue to buy tickets for screenings of The Room because it’s so readily apparent from scene to scene what Tommy Wiseau has in mind, as well as the degree to which he misses the mark. When Wiseau decided a scene meant to convey male bonding should involve a bunch of guys in tuxedos awkwardly tossing a football to each other in an alley, it’s hard not to be mesmerized by the enormous gap between intention and execution. But the intent was there.

In Southland Tales, it is never clear what Kelly is aiming for, on either the micro or the macro scale. Tones and moods butt up against each other; in individual scenes, characters behave as thought they’re in different movies. It’s not hard to see how this might happen in a narrative that focuses on Bush-era paranoia, surveillance, porn star reality shows, the apocalypse, time-travel, secret societies, meta-screenplays, Neo-Marxist resistance movements, amnesia, a drug called Fluid Karma, and a flying ice cream truck. But still.

At one moment, Southland Tales seems to be rooting around in the same soil as Idiocracy (released the same year): World War III is sponsored by Hustler Magazine and Bud Light, a political ad portrays to SUVs having graphic car sex, Sarah Michelle Gellar’s porn star, Krysta Now, spouts gibberish on her TV show and is promoting a record called “Teen Horniness Is Not A Crime”.

But meanwhile, Seann William Scott is involved in a sci-fi melodrama played almost entirely straight. Dwayne Johnson does a comic thing with his fingers from time to time and gets to mug a little bit, but generally seems to have arrived from an action and/or spy movie. Wallace Shawn, bent on world domination, is dressed like a rave-wizard with unlimited credit at JoAnn’s Fabrics. When not inscrutably narrating the story from a machine gun turret in the ocean, Justin Timberlake likes to stop the film entirely to lip-sync to The Killers, while bewigged, dancing nurses swarm around him.

And there’s the whole thing with the space-time continuum.

What could it possibly all mean? Perhaps to assist us, Kelly fills Southland Tales with literary and film references. This is another of his quirks, on display in Donnie Darko (E.T., Stephen King’s IT, Graham Greene, Watership Down) and The Box (Sartre’s “No Exit”) as well, but he takes it to the point of absurdity here.

This is a film that draws heavily on The Book of Revelation, which Timberlake’s Pilot Abilene is constantly reading. (Abilene was also one of the Texas towns nuked in the intro.) T.S. Eliot’s “The Hollow Man” makes several appearances. The suspiciously George W. Bush-like vice-presidential candidate quotes Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken,” twice. (Also, his character’s name is Bob Frost. Funny?) Langston Hughes’ “miles to go before I sleep” is pointedly deployed. Unsurprisingly, the Neo-Marxists enjoy casually tossing in some political philosophy (“Anyone who knows anything of history knows that great social changes are impossible without feminine upheaval”), though it’s hard to know what to make of a Marxist group who use anarchy symbols in their logo. For some reason, the lyrics to Jane’s Addiction’s “Three Days” are repeatedly cited without context.

Robert Aldrich’s 1955 weirdo-noir Kiss Me Deadly serves as something of an organizing theme in Southland Tales, much as it did a decade earlier in Pulp Fiction (though the apocalyptic notes of Aldrich’s classic seem more at home here). It’s playing on TV when two central characters meet, and it’s playing in the background again at the climax. The name Dr. Soberinn Exx (Curtis Armstrong … yes, Booger from Revenge of the Nerds, just one of the dozens of odd casting choices) is a direct reference to the evil doctor of Kiss Me Deadly.

Meanwhile, Mulholland Drive‘s Rebekah Del Rio shows up to croon for us again, and Johnson’s character — both in his screenplay and the film-within-the-film that draws from it — is named Jericho Cain, the moniker of Arnold Schwartzenegger’s protagonist in the 1999 action movie End of Days.

So that should clear things up. (For a heroic attempt to list these out, see Thomas Rogers in Salon.)

But to get back to the central idea here, the cumulative effect of all this navel-gazing and jarring tonal shifts isn’t to generate intrigue but exhaustion, just as the individual scenes don’t reveal a weird, mesmerizing tension but a flatness. While cult favorites often move towards narrative inexplicability, the particular variety of ambitious overreach in Southland Tales seems more like a director demanding his film be decoded. This is not a good look, and the movie’s insistence on being grappled with actually keeps the viewer at a distance instead.

Still, while these things might constitute roadblocks to cult status, Southland Tales has so many ideas that it proves compulsively watchable. I spent my first viewing laughing and shaking my head at how misconceived it truly is … then watched it again the next day.

There are some scenes that really work well, and if it fails to cohere, it’s never dull. When Timberlake says, “Venice Beach was the home to the Neo-Marxist underground. They were the disciples of the German philosopher, Karl Marx,” it’s unclear whether Kelly meant it to be funny, but I laughed both times.

There’s even an argument to be made that the sheer enormity of exposition and narrative, and its frantic aesthetic, make Southland Tales an ambitious failure that nevertheless expressed much about the period in which it was made. When Kelly divides the screen like a DVD-chapter menu, with jabbering talking heads all telling us aspects of the plot at once, it could be construed as a commentary on information overload. The references bounce off each other in ways too opaque to process. And all the while, surveillance cameras capture our every move, as tyrants extend their grip on power and our identities as citizens, or even stable personalities, become increasingly less coherent. This would remain relevant today.

Or maybe Southland Tales is just a mess, as many people conclude; a second-time director granted a staggering amount of studio resources to capture every idea he ever had, then methodically editing away to the point of incoherence. It’s still a fascinating, enervating film to encounter, if only to ask, “What was everybody thinking?”

In a less-than-rave at the time of its release, Roger Ebert, citing ambition but failure to stick the landing, called Donnie Darko “the one that got away.”

Of course, he hadn’t seen Southland Tales yet, which really seems to earn this title through sheer, baffling conviction. It might never attract a committed enough audience to constitute a bona-fide cult classic, but there’s no denying its wild ambition, and even wilder missteps.