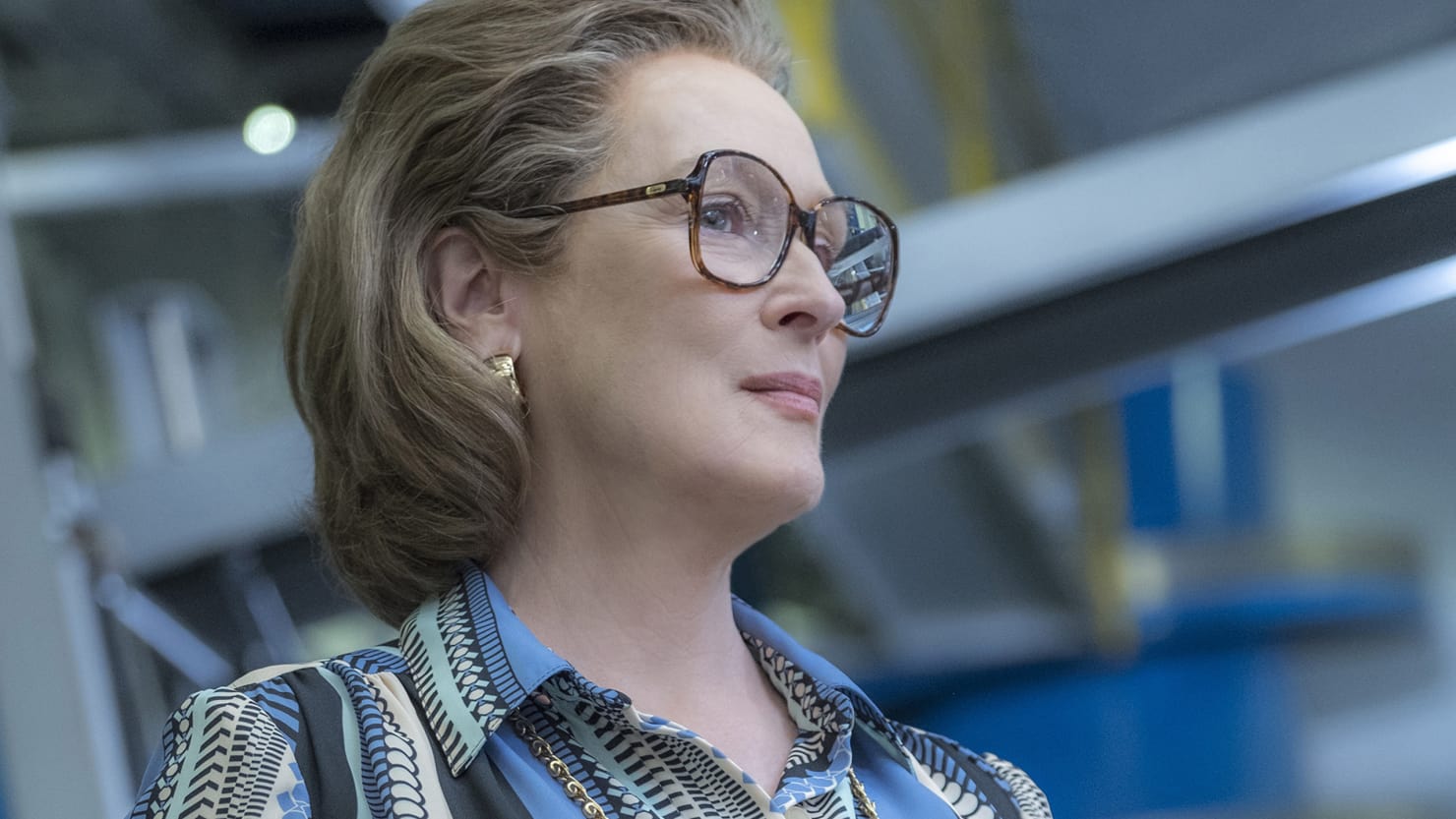

Late in The Post, we have the scene, mandated by genre, in which Meryl Streep, trying to make the ethically right decision, talks to her daughter about a memory of the daughter’s childhood — the place in which the daughter, who has been vaguely rebellious, tells her to do what she thinks is right.

Streep recalls how, when her husband died, she needed to make a speech to the board of the Washington Post, of which she was suddenly the owner. Her daughter came out “in her little nightdress” and handed her … a list of points to hit in her speech. (She makes her daughter read it again: it begins “1: Thank them for their attendance,” and devolves from there.)

One can imagine another film, one of a Damien-like character, a sociopath who has watched too much West Wing. But the incredible awkwardness of the scene, which is hilarious (Rick mentions it in his original review of the film), is wholly representative of the film’s complete lack of a heart — or, at least, representative of one of the films within the film.

Because there are at least three, with room for a couple more small ones here and there. There is the standard period film, shot almost entirely in standard shot-reverse shot style, which can be safely ignored.

There is the desperately 70s-aping film, the one that wants to be another All the President’s Men. This is the film occupying the screen in the several long, still shots in the opening minutes.

In these scenes — for example, the excruciatingly long one in which Streep and Hanks first share the screen and awkwardly banter at a meal — one can hear Spielberg trying to capture the overlapping and muffled dialogue of President’s Men. But he can’t let go of his dialogue long enough to actually do it. Instead, we just end up with traded quips ducking beneath one another, like the film slipped into fast-forward.

In these scenes — for example, the excruciatingly long one in which Streep and Hanks first share the screen and awkwardly banter at a meal — one can hear Spielberg trying to capture the overlapping and muffled dialogue of President’s Men. But he can’t let go of his dialogue long enough to actually do it. Instead, we just end up with traded quips ducking beneath one another, like the film slipped into fast-forward.

The problem is, the film can never be President’s Men, for narrative reasons as much as aesthetic ones. Woodward and Bernstein chase leads, and spend half the film shooting blanks and wasting time.

The protagonists of The Post get their story, literally, dropped onto their desk. (They do have to do some follow-up work: two payphone calls.) The overlapping dialogue that The Post occasionally tries to bring to mind is just chatter in its structure, because there is no danger of missing information. The heroes already know everything; the only question is if they will get a chance to share their beneficence with the world.

This brings about the third film, and the third shooting style, borrowed mostly from The West Wing. Unfortunately, most of the characters can’t do too many walk-and-talks — it’s hard to walk-and-talk with one ear to a corded phone, and too much of Tom Hanks’ brain is occupied flexing every muscle in his face to also handle bipedal movement — so the camera is forced to make up the difference.

This brings about the third film, and the third shooting style, borrowed mostly from The West Wing. Unfortunately, most of the characters can’t do too many walk-and-talks — it’s hard to walk-and-talk with one ear to a corded phone, and too much of Tom Hanks’ brain is occupied flexing every muscle in his face to also handle bipedal movement — so the camera is forced to make up the difference.

You can tell the Sorkin-aping thread of the film, then, by the constantly moving camera. One imagines this is the last time Zach Woods will be on the receiving end of a dramatic, slow zoom.

The three styles (dully prestige, 70s-aping, and Sorkinesque) all give the film shots that, on their own, are coherent and which fully express their own thought, but placed together make everything schizophrenic. Somehow the film breaks the most basic rules of editing, like 180- and 30-degree rules. If you look closely, you can even see the color balance and lighting shift between shots in strange ways.

But beyond a confused aesthetic, probably caused by the hurried production schedule, the schisms between the film styles leave their mark on its principles. Lacking an investigation, most of the film is taken up by the question of whether or not to print the Pentagon Papers.

It would be easy to plant the decision on strong moral footing by emphasizing their real importance: that they revealed the extent to which the American government had stuck to the moral evil of the Vietnam war to avoid being embarrassed. And there are a few hints in that direction, but, so as to maximize its real-life impact, the question is instead that of Freedom of the Press. (Somehow, we only have one brief mention of the fact that Streep’s son, who is never seen, just returned from Vietnam himself!)

The endless speeches about the freedom of the press raise in prominence at the same rate the Sorkinesque style takes over the film, and this is not a coincidence. The West Wing is the darling of liberals because it manages to act like a vision of a progressive future while having its heroes constantly make the “pragmatic” decision — that is, sell out their values to stay in control so that they can ostensibly do something good at some unstated future point.

The endless speeches about the freedom of the press raise in prominence at the same rate the Sorkinesque style takes over the film, and this is not a coincidence. The West Wing is the darling of liberals because it manages to act like a vision of a progressive future while having its heroes constantly make the “pragmatic” decision — that is, sell out their values to stay in control so that they can ostensibly do something good at some unstated future point.

The Post is similarly pragmatic. If the film ended when Streep makes the decision to print, it could claim to believe in something, but it doesn’t end until the Supreme Court has ruled in the paper’s favor, until they get to talk about how their IPO has not been harmed by the release, until we see every other newspaper following in its wake. So it is not about standing by your virtues, even when people are against you — it’s about backing the right horse, and knowing that at that time, bucking the government was a better investment than obeying it.

The real horror of Vietnam barely comes up because it would interrupt the free flow of fantasy that the film offers. Our heroes in the film were pragmatic people who Know the Score and just want to get that information to the people, just like the filmmakers themselves Know the Score — they know who all these newspapermen are, unlike those rubes outside of big cities, unlike those millennials who don’t even know how typewriters work — and are telling an important story to the people, just like we in the audience Know the Score because we chose to watch The Post.

The real horror of Vietnam barely comes up because it would interrupt the free flow of fantasy that the film offers. Our heroes in the film were pragmatic people who Know the Score and just want to get that information to the people, just like the filmmakers themselves Know the Score — they know who all these newspapermen are, unlike those rubes outside of big cities, unlike those millennials who don’t even know how typewriters work — and are telling an important story to the people, just like we in the audience Know the Score because we chose to watch The Post.

The only people missing are those harmed by the evil the government does, just as the victims of ICE (and others) are missing in the stories of the corruption of Trump.

The Post makes a game attempt at feminism here and there, but its vision of feminism is just a more equal distribution of authority and power. (It is hard to tell how much of Streep’s performance is consciously trying to evoke Clinton, and how much it is just that she often evokes Clinton, but I lean towards the purposeful.)

I don’t know if The Washington Post’s website still attaches “Democracy Dies in Darkness” to every article you see, but I know many leftists had fun making that banner appear above its mad push for the Iraq War. The sad thing is, one can imagine a version of The Post about those exact murderous articles. Because The Post doesn’t have any particular values except a celebration of its own power and a vague promise that when these technocrats rule, half those in charge will be women.