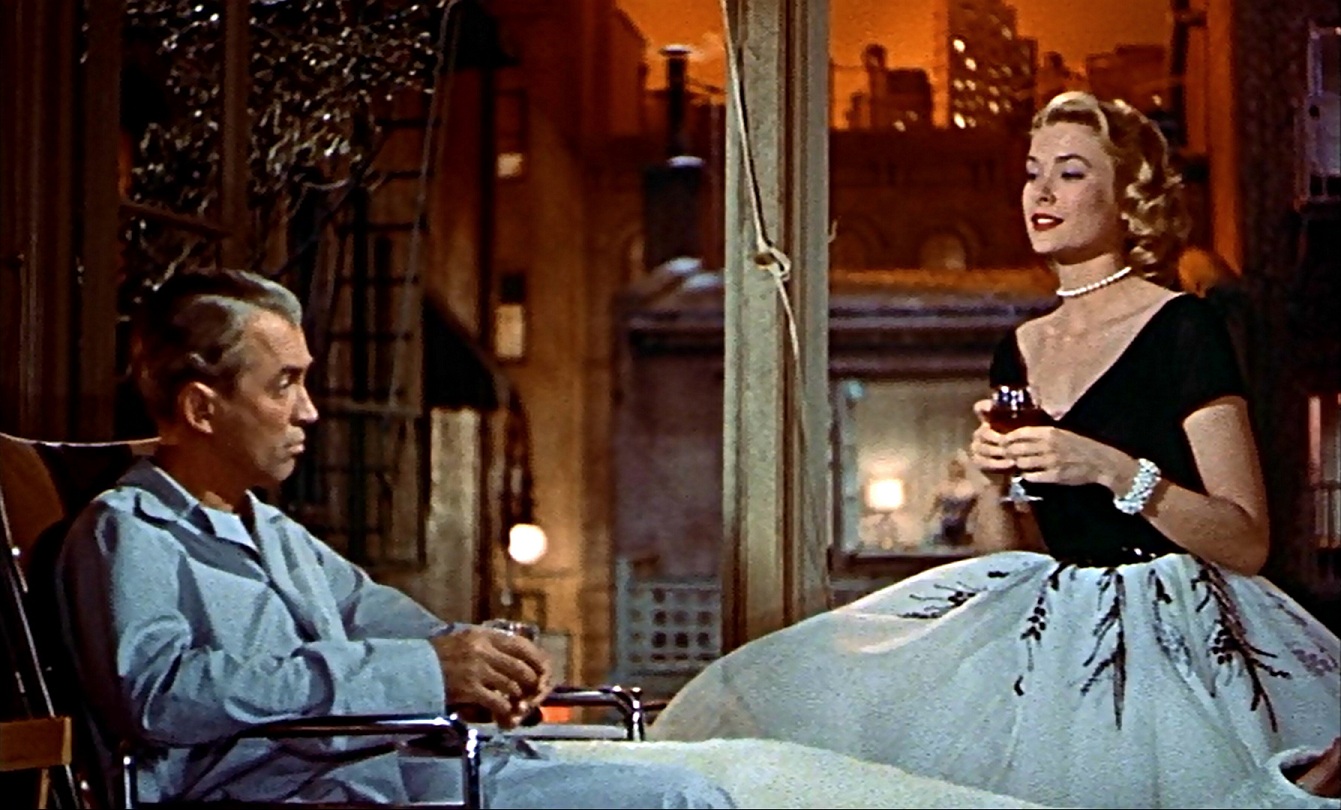

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window is a true classic, beloved by cinephiles, critics, theorists, and casual moviegoers alike. Masterfully layered, featuring some of the best work its illustrious cast ever turned in, and providing analytical fodder for countless analyses of its themes and artistry, Rear Window unquestionably earns its place in the pantheon of masterpieces.

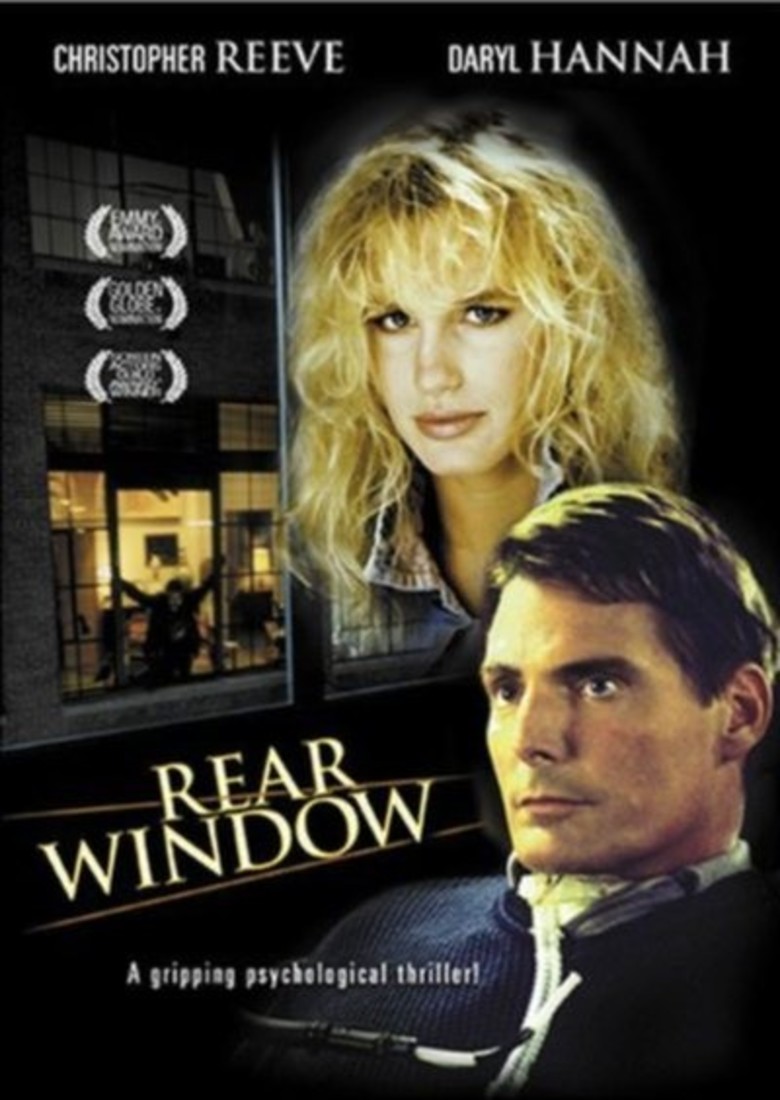

None of these things, I am sad to report, can fairly be said about 1998’s Rear Window, a made-for-TV adaptation I didn’t realize existed until Netflix thought I might like it. (Is this possibly related to a diminishing collection of streamable films on the service? In a word, yes.)

Starring Christopher Reeve in his first major appearance after a horrific accident resulted in his near-total paralysis, this weird, sad iteration of Hitchcock’s vision misses almost everything audiences enjoy about the original. It’s a truly uncanny sight to behold, and watching it carries more than a whiff of shame. The film does perform one useful service, however — it throws into stark relief the mastery of the original it so thoroughly bungles.

To be clear, I have not come to mock Christopher Reeve’s excruciatingly ill-advised decision. It’s impossible to really laugh at Rear Window ’98: that would be uncharitable at best and monstrous at worst. But you do have to wonder who thought this was a good idea, and allowed it to occur.

The Reeve adaptation hew fairly close to the original’s plot-beats — we are in an apartment with an immobile protagonist, there’s a possible murder across the way, there’s a blond love interest, and so forth — but it’s really after something else. Reeve and the writers use the familiar trappings of Hitchcockian suspense and voyeuristic kink to craft an issues drama instead. Adam-Troy Castro explains:

[B]y the time it was made, Reeve was quite rightly an advocate for spinal cord research, and for state-of-the-art medical treatments for people with spinal cord injury…and as such, acutely aware that this movie, by far his most substantial acting role after the accident, was the best place to advocate for his cause. So he made demands, and nobody involved with the production had the heart or the good sense to say no to him. So it begins with him in the hospital, features him declaring that he will walk again someday, and includes scenes of him undergoing arduous physical rehabilitation to triumphant music long before he even gets to the apartment where he will observe the murder across the way.

Rather than a razor-sharp script with clearly delineated characters interacting in service to the claustrophobic thriller at hand, we find ourselves in hospitals and rehabilitation wards. Noble, to be sure, but not exactly the stuff of suspense films. (There’s a reason Wait Until Dark isn’t primarily about the scientific race to fix Audrey Hepburn’s sight.)

An original that prompted Laura Mulvey to ruminate on the depiction of the “male gaze”, Roger Ebert to consider the Kuleshov effect and the possibility that Jimmy Stewart’s cast represents his character’s impotence, any number of shot-by-shot analyses, and whatever this glorious madness is, Reeve and director Jeff Bleckner opt in their advocacy to focus on all the new technology available to quadriplegics. The story of what’s going outside the, um, rear window of the apartment is for all intents and purposes secondary.

On top of this, basic changes chip away at the subtext and import of Hitchcock’s construction. Instead of one of the greatest indoor sets ever created, Reeve’s ultra-modern apartment robs the film of the intimacy that animates the original. It’s more High-Rise than Hitchcock. In the original, the heat wave and lack of A/C compels neighbors to engage more than they otherwise might; here, it is baffling why people don’t just pull down the shade.

The memorable figures of Miss Lonelyhearts, Miss Torso, the piano player, the older couple who sleep on the fire escape … all replaced with meaningless stand-ins. It becomes remarkably clear how, in Hitchcock’s vision, the tableau across the way represents a cross-section of different possibilities for Jimmy Stewart’s character and his future, a man-of-action grappling with immobility and a self-declared bachelor confronting commitment and/or performance issues with regard to impossibly angelic Grace Kelly (an unusual problem, to be sure, but fair enough in context). The 1998 version jettisons all of this; the filmmakers seem to have understood nothing at all about the why the neighbors are there.

An all-purpose, and immediately nasty, villain takes over for Raymond Burr’s desperate, creepy husband, further eroding the original’s “did he or didn’t he?” tension. There’s never the smallest doubt that the guy’s a killer; perhaps because we spent so long dealing with the daily indignities of disability, there’s no time left to engender any dread. A kind of flatness and inevitability takes hold.

Even the voyeurism, that most Hitchcockian trope, is dead and buried, like a small dog who’d been sniffing around and getting a little too close. Famously, Stewart’s J.B. Jeffries is a renowned photographer — this couldn’t possibly be more important to the film. Reeve, on the other hand, is an architect, which couldn’t possibly be more meaningless, except insofar as it grants him some expertise to super-tech his apartment and hang out with colleague Darryl Hannah, who at all times looks like an actress doing her friend a favor.

Finally, a few nice words. Despite the film’s programmatic insistence on uplift at the expense of story, Reeve is often very good. His schoolboy charm is communicated through that superhero smile, and so much of this comes from a place of pain that it’s impossible to avoid a real sense of empathy. Robert Forster is always a welcome presence, filling in the Wendell Corey role as a skeptical detective. The oversized absence of Thelma Ritter is deeply felt, but there are some touching scenes with Reeve and the crew that surrounds him, trying to help integrate him back into a world that has seemingly left him behind.

None of which, of course, has anything to do with the original the film purports to be “updating”. As a passion project and a testament to a pretty unbelievable work ethic on Reeve’s part, the 1998 Rear Window can be appreciated on its own terms, even if it is not very good. Unlike, say, Gus van Sant’s Psycho, this is not the sort of thing to dismiss as utterly inessential. It’s a curious failure, a well-intentioned series of missteps and ill-advised decisions married to the structure of a classic that didn’t need an update in the first place.

But it’s in those failures and missteps that it performs an admirable service: it makes you want to watch Hitchcock’s version again as soon as possible.