On the face of things, Robert Greene‘s Bisbee ’17 and Lee Ann Schmitt‘s Purge This Land don’t look a lot alike. They’re both documentaries, and they both screened at the recently-concluded San Francisco International Film Fest, but in subject and approach, they seem worlds apart. Closer looks dispel that notion.

If we can be a tad reductive for a minute (and we can), we can think of the documentary tradition running as parallel streams, the observational and performative. Flaherty complicated this right out of the gate with Nanook of the North in 1922 — an observation of a quasi-performance — but it works well enough in broad strokes.

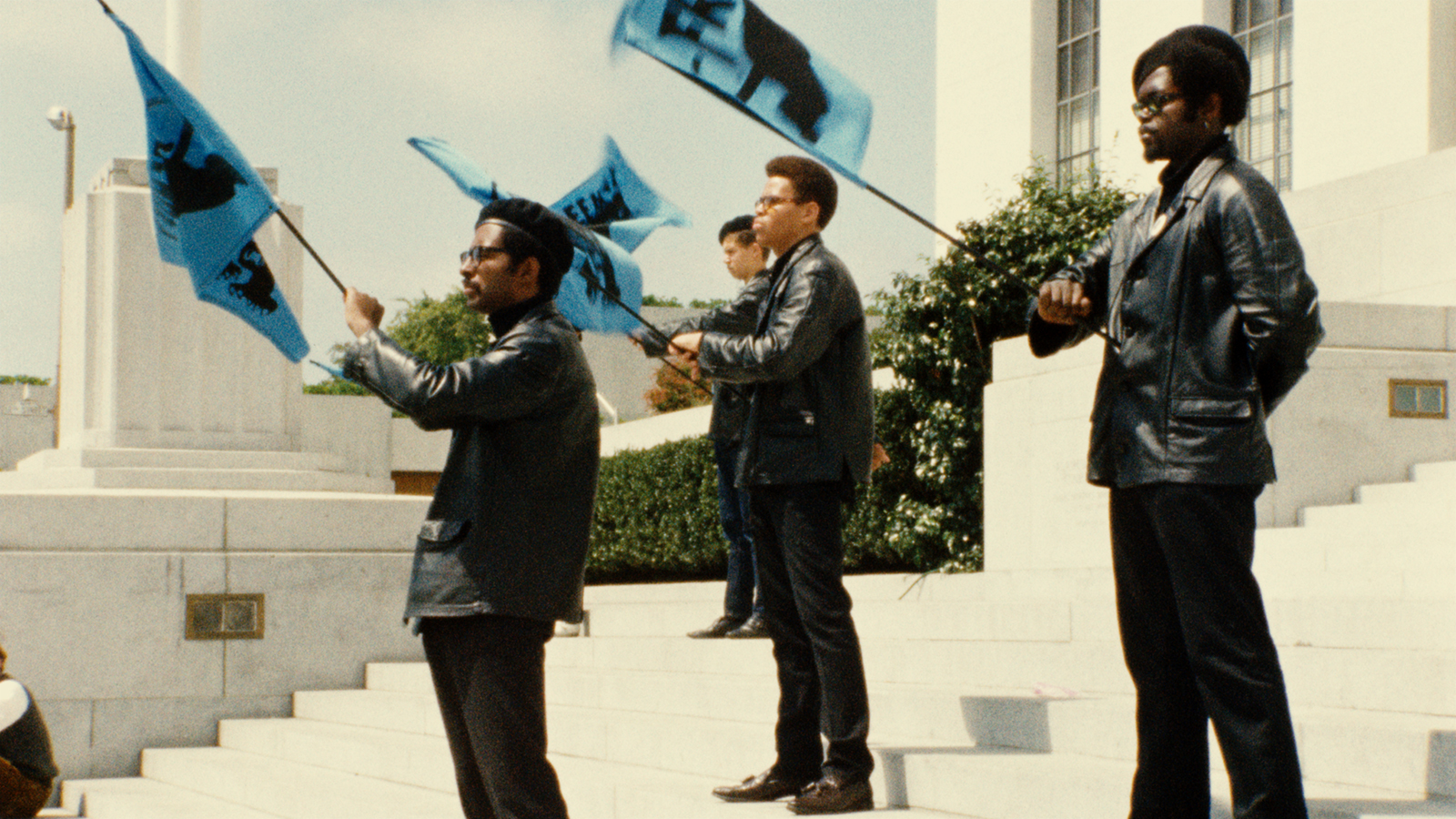

You can find it in the talking head/archival model abutting the discursive essay film (Hearts and Minds vs. Far From Vietnam), or the fly-on-the-wall contrasted with the recursive loop (Varda‘s Black Panthers vs. I Am Not Your Negro). More recently, Joshua Oppenheimer helpfully made companion pieces from opposite banks, with The Act of Killing‘s performative poeticism refracted, two years later, in The Look of Silence‘s observational, committed detachment. The ambitions might be pedagogical in both cases, but the aesthetic approaches differ greatly.

You can find it in the talking head/archival model abutting the discursive essay film (Hearts and Minds vs. Far From Vietnam), or the fly-on-the-wall contrasted with the recursive loop (Varda‘s Black Panthers vs. I Am Not Your Negro). More recently, Joshua Oppenheimer helpfully made companion pieces from opposite banks, with The Act of Killing‘s performative poeticism refracted, two years later, in The Look of Silence‘s observational, committed detachment. The ambitions might be pedagogical in both cases, but the aesthetic approaches differ greatly.

The documentary programming at SFIFF underscored this. Something like The Rescue List, its stylization aiming at verite and its heart on its sleeve, wants to inform, outrage, generate action through teaching. Its camera does not lie, or claims not to; we are meant to imagine that the camera is not even there, that we have been granted a window into this world, with lessons to take back to ours. Shirkers, on the other hand, is a nesting doll of absences — a time-warped film about a film lost to time, a collection of moods and sensibilities that evoke more than they transmit. To reduce further, it’s something like the Lumières and Méliès.

It’s not that neat, of course. The real point of any category exercise is to knock it out at the knees. Both Bisbee ’17 and Purge This Land occupy strange middle territories, freely borrowing elements from these aesthetics to interrogate them, bend them to other uses.

Like much of Greene’s work (Actress, Kate Plays Christine), Bisbee ’17 is performative in the most literal sense. The film details a largely forgotten moment in labor history — the strike-breaking deportation of 1,200 miners from Bisbee, AZ, the Wobbly leaders and the mostly immigrant workers loaded on trains by friends and family and shipped off to the desert to die — through the documentation of its re-enactment on its centennial.

Like much of Greene’s work (Actress, Kate Plays Christine), Bisbee ’17 is performative in the most literal sense. The film details a largely forgotten moment in labor history — the strike-breaking deportation of 1,200 miners from Bisbee, AZ, the Wobbly leaders and the mostly immigrant workers loaded on trains by friends and family and shipped off to the desert to die — through the documentation of its re-enactment on its centennial.

This foundational moment in a town’s story hides in plain sight, ideologically undergirding the now-abandoned mine. The mine itself still powers most of Bisbee’s remaining economy, with descendants of miners and company men playing tour guide for visitors, or acting out the events of the OK Corral in nearby Tombstone. (The lingering animus between Bisbee and Tombstone, fighting for fleeting notoriety, is an interesting footnote.)

The remaining retail outlets of Bisbee are staffed by another batch of first-generation immigrants, one of whom, embodying a fictitious miner, will sing “Solidarity Forever” as Bisbee ’17 briefly becomes a musical, a stirring moment in Greene’s tapestry of the real.

Bisbee ’17 actively intervenes in its telling of history; cameras in the frame foreground its artifice, and Greene draws attention to the way the recontextualized past is experienced as present through its staging. It’s a lie that aims at truth. You don’t walk away from Bisbee ’17 simply knowing more about the events it depicts; Greene’s film aims to make you feel what it is like to know, to question what knowing entails. It is a flurry of significations in constant dialogue.

By contrast, Purge This Land is almost entirely still, oblique enough to invite charges of inscrutability. As the title quote indicates, this is a meditation on John Brown, but it’s a meditation that feels outside of time and context. We see fields, flowers, small movements in the wind. Broken-down barns on the outskirts of large cities, water and sky, advertising structures and historical plaques no one reads anymore. The camera is motionless, shot lengths creep ever upward, it’s observational in the extreme. But what are we observing?

By contrast, Purge This Land is almost entirely still, oblique enough to invite charges of inscrutability. As the title quote indicates, this is a meditation on John Brown, but it’s a meditation that feels outside of time and context. We see fields, flowers, small movements in the wind. Broken-down barns on the outskirts of large cities, water and sky, advertising structures and historical plaques no one reads anymore. The camera is motionless, shot lengths creep ever upward, it’s observational in the extreme. But what are we observing?

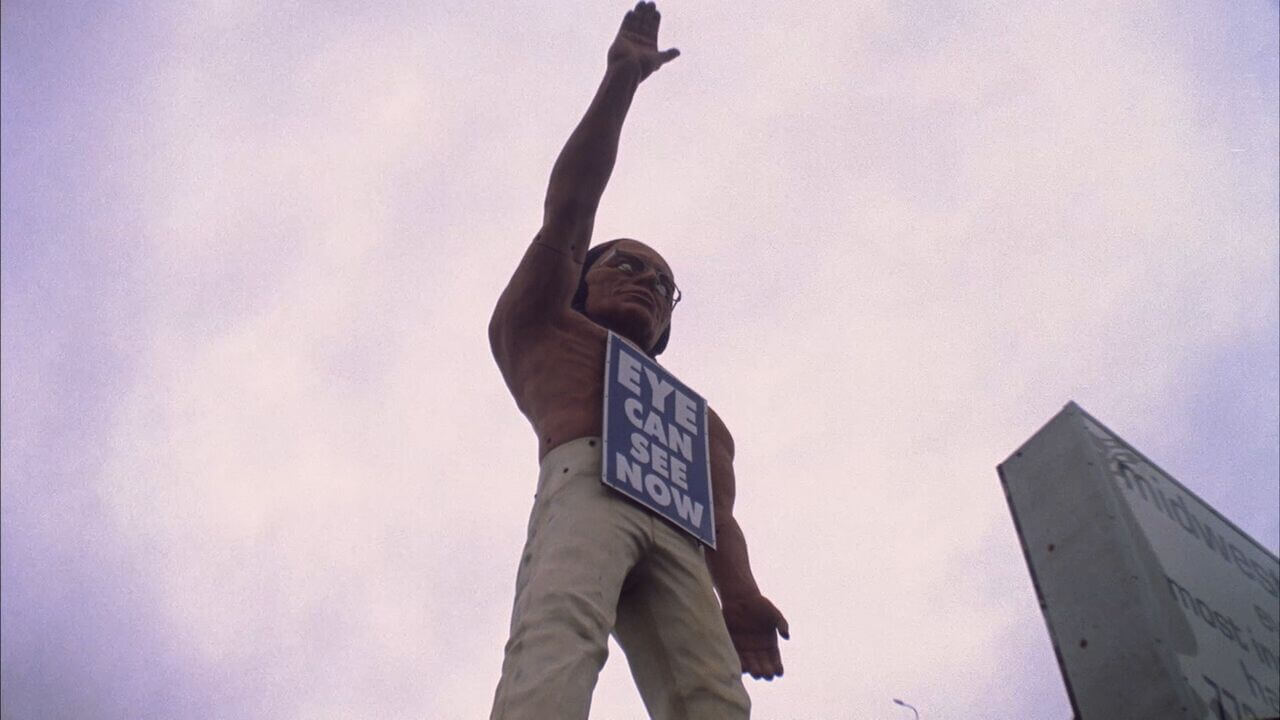

There are virtually no humans on screen — Schmidt is uncomfortable with the political implications of such representation, with capturing bodies in the service of imaginative liberation. Her narration weaves the history of American racism and revolts into the police murders of today, her anxiety as the white mother of a Black son as palpable throughout as the frenetic score. (It’s from her partner Jeff Parker, of post-rock stalwart Tortoise, interweaving generations of Black music with the strains of “John Brown’s Body”; this was, in turn, the model for “Solidarity Forever,” the venerable labor standard that someone in Bisbee ’17 denounces as unpatriotic. Circles inside circles.)

Meanwhile, we look at the land, the places Brown lived and traveled, the house where he spent a final night with Frederick Douglas, who declined to accompany him on his doomed mission. Schmitt’s film doesn’t editorialize, but the authorial presence is there all the same. We are left wondering how a stubborn gaze, a refusal to zoom or pan, even could editorialize, but we feel it. What are these objects, these landscapes? What do they reveal or hide? What do they “mean”? Why are we being asked to look, and look, and look closer? There’s something unsettled. We become unsettled.

Meanwhile, we look at the land, the places Brown lived and traveled, the house where he spent a final night with Frederick Douglas, who declined to accompany him on his doomed mission. Schmitt’s film doesn’t editorialize, but the authorial presence is there all the same. We are left wondering how a stubborn gaze, a refusal to zoom or pan, even could editorialize, but we feel it. What are these objects, these landscapes? What do they reveal or hide? What do they “mean”? Why are we being asked to look, and look, and look closer? There’s something unsettled. We become unsettled.

So both Bisbee ’17 and Purge This Land draw from both streams, almost rigorously observational in their performativity and indeterminate authorship. In documentary films, as elsewhere, it’s in the category lapses that things become really interesting.