In 1998, two movies were released: The Truman Show and Dark City. Although they both revolved around a protagonist who realizes the city in which he lives is “fake” — an elaborate form of reality television in the former, an alien sociology experiment in the latter — they don’t seem too similar on their own.

But in 1999, three more movies were released: eXistenZ, The Thirteenth Floor, and The Matrix. All 3 movies had an extremely similar plot, in which the protagonist realizes that the world they live in is “fake”; they all, in fact, took it further to reveal that the world is a computer simulation.

But in 1999, three more movies were released: eXistenZ, The Thirteenth Floor, and The Matrix. All 3 movies had an extremely similar plot, in which the protagonist realizes that the world they live in is “fake”; they all, in fact, took it further to reveal that the world is a computer simulation.

This means that in 15 months, 5 different movies came out with the basic premise of the world being fake. (Dark City was released on February 27, 1998; The Matrix was released on May 28, 1999.)

Why? There is certainly an element of chance operating in the intense concentration — as much of a materialist as I am, I’m not suggesting that something was special about those 2 particular years that made this happen — but it certainly is something worth examining.

The 3 computer-reality films could be explained by the development of computers, but I don’t think it’s so simple. First, that doesn’t explain The Truman Show or Dark City, which are unrelated to computers. Second, the source material for The Thirteenth Floor (the novel Simulacron-3) was released all the way back in 1964 (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, of all people, adapted it for German TV as World on a Wire in 1973), and that was hardly the first story of its kind. And third, 1990s computers were not much closer to computer-simulated consciousnesses than we are now.

The 3 computer-reality films could be explained by the development of computers, but I don’t think it’s so simple. First, that doesn’t explain The Truman Show or Dark City, which are unrelated to computers. Second, the source material for The Thirteenth Floor (the novel Simulacron-3) was released all the way back in 1964 (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, of all people, adapted it for German TV as World on a Wire in 1973), and that was hardly the first story of its kind. And third, 1990s computers were not much closer to computer-simulated consciousnesses than we are now.

I’ll be upfront about this: I have no idea why these films came out at this point in time. These pieces are more of a sketchbook towards a theory about them than anything final. With no further ado, let’s talk about Dark City.

—

Nothing dates Dark City like its attempts to be timeless. In an attempt to confuse the viewer, the titular city freely mixes a number of temporal markers, but the backbone is noir time, that ambiguous superimposition of the 1930s onto the 1950s. That aesthetic, however, is reflected through a distinctly 1990s lens, a distortion nowhere more visible than the scenes set in the bar in which Jennifer Connelly, a jazz club singer, works.

Even by the standards of neo-noir jazz, which is itself a more recent invention — the number of original noirs that have prominently jazz soundtracks can be counted on both hands — this sounds nothing like the period it is trying to evoke.

Even by the standards of neo-noir jazz, which is itself a more recent invention — the number of original noirs that have prominently jazz soundtracks can be counted on both hands — this sounds nothing like the period it is trying to evoke.

This isn’t to knock the movie for being of its time — everything is, if we’re honest — but to try to situate its gestures. Kiefer Sutherland’s bizarre performance more than any other can help us decipher what is happening with the free temporal borrowing. He plays his character (named Daniel Schreber, an unsubtle reference to the 19th century German judge who wrote Memoirs of My Nervous Illness from a mental institution suffering from paranoid schizophrenia) as a slightly more goyish version of Peter Lorre’s Ugarte, pausing every few words to suck air in.

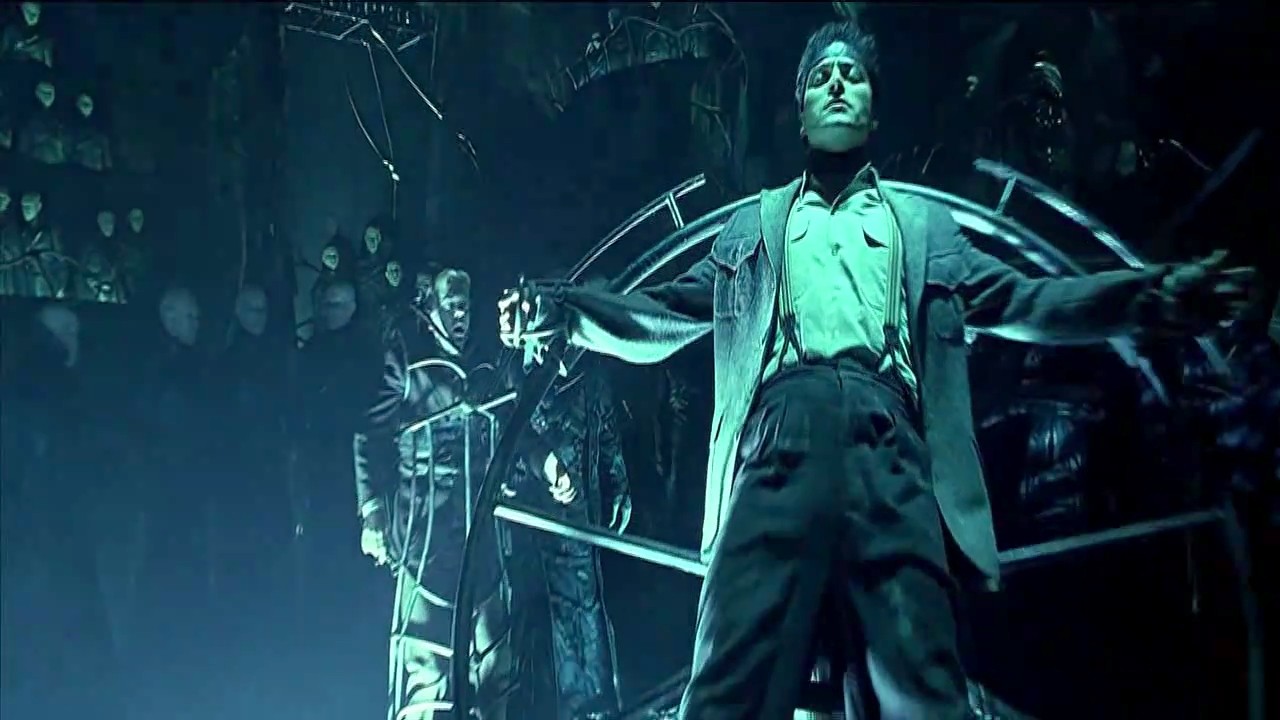

It’s a next-level insane performance, almost entirely tick. It begins to make more sense once it is revealed that he is a Quisling for the pale, bald creatures who run the city and who are falsifying everyone’s memories. As a former psychiatrist he is apparently particularly gifted at synthesizing fake memories in a lab.

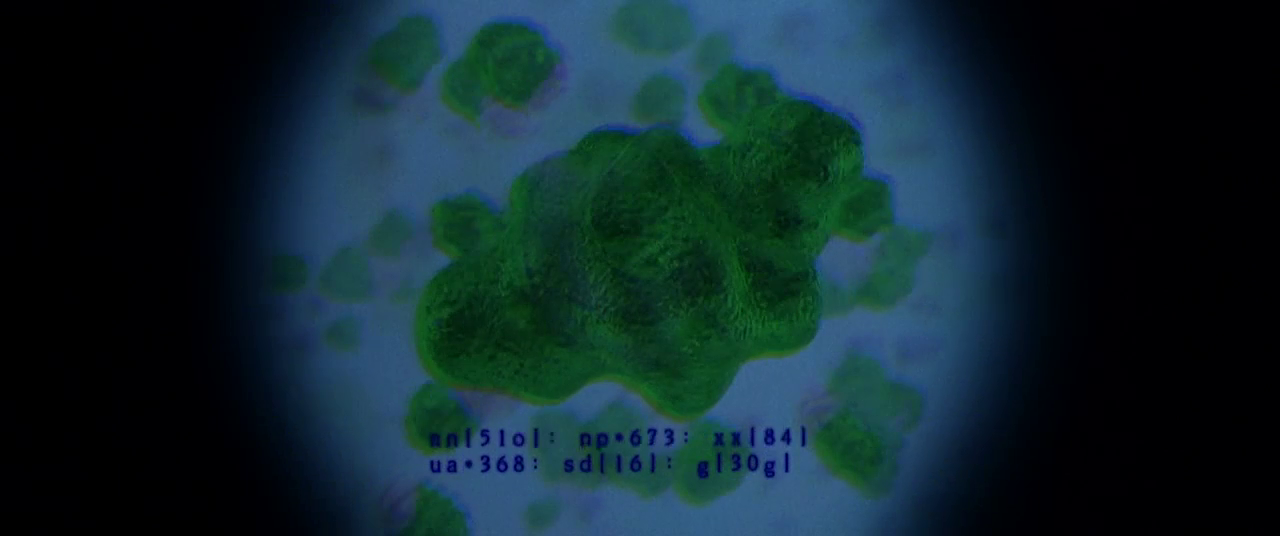

Synthesizing is very literal here. In one incredibly silly scene, Sutherland looks through a microscope at science-y looking blobs and literally mixes memories together. “A touch of unhappy childhood,” he says, “good. Ah, a dash of teenage rebellion… and last, but not least, a tragic death in the family.” A death in the family is represented, of course, by green goo.

Synthesizing is very literal here. In one incredibly silly scene, Sutherland looks through a microscope at science-y looking blobs and literally mixes memories together. “A touch of unhappy childhood,” he says, “good. Ah, a dash of teenage rebellion… and last, but not least, a tragic death in the family.” A death in the family is represented, of course, by green goo.

I wish to briefly be unfair to this movie. As a teenager, I wasn’t really aware of the time period from which the movie was drawing; honestly, it just looked cool. But rewatching it now, it is hard not to think about the repercussions of relying so heavily on a 1930s German expressionist aesthetic. We don’t have to directly compare the appearance of anti-Semitic caricatures to the evil aliens who run the city to notice some similarities in their function.

The parasitic aliens are both parasites on the city and the city’s creators. They are both invincible and impotent — our hero ends up vanquishing them all without much effort. They’re the definition of the fascist’s target, as Eco describes it: so invincible they must be destroyed for our own safety, and so pathetic they should be destroyed for their own good. They are responsible for all the corruption present in human — meaning European white — culture, trying to turn the hero subconsciously into a serial killer of prostitutes as a sociological experiment. They are, in short, the furthest point of the Other-figure.

I’m not saying that this is a fascist movie, whatever that might mean, but in making use of the 1930s German milieu Dark City has replicated the basic ideas that make it such a fascinating moment in film history. By putting this in the context of the “fake world” idea, it reveals something about the fantasy of the 1930s — and the 1990s.