Last week, I checked back in with the Twin Peaks subreddit. I was mostly curious to see how the quest for theories was going, weeks after the finally final finale. It was stupid not to realize what I was actually going to get, given the fast-approaching holiday – pages and pages of Halloween costumes, of course (Dale Cooper for anyone who could afford a suit, with some dudes who were probably already halfway to looking like the Woodsmen filling out the rest of their aesthetic).

But I did find some of what I was looking for. I wasn’t aware a new Twin Peaks book was coming out: another Mark Frost novel (The Final Dossier) to inspire another round of grand theories of what was Really Going On in the world of Twin Peaks. These theories had been bubbling up over the entire course of The Return, in that subreddit and elsewhere, playing the same guessing game people on the Internet play with every show.

During Twin Peaks’ run, I had spent a lot of time mocking this kind of theory-crafting wherever it popped up. It seemed obvious to me that the show was never interested in giving the kinds of answers these theories were looking for. And the reason for that light contempt was based on a very particular understanding of David Lynch and his work.

The Lynch revealed in his films is a fetishist in the purest sense. They reveal a creator who has become so engrossed in a particular fantasy – the curtain that is about to part, revealing, on stage, both the sexual being and the solution to the puzzle – that that fantasy has become more satisfying, with its promise of satisfaction, than the satisfaction is itself. It’s present in his view of sexuality, which views the performance of sexiness as closer to sex than sex itself, and is present in his narrative: that he is more interested in the structure of the almost-here reveal than the reveal itself.

His narratives tend to be structured around constantly parting curtains – curtains that never open all the way up to the pleasure and resolution of the “event,” but only to more curtains. This isn’t completely metaphorical. I think it’s in Lynch on Lynch that he talks about his particular attraction to the Dance of the Seven Veils (not to mention Twin Peaks‘ Red Room, with its curtain lining that keeps revealing more and more hallways).

So, I thought, cockily, anyone spending time trying to bring resolution to the world of Twin Peaks, or to any Lynch production, was missing the entire point. There is no resolution, only a continual parting of curtains. Anyone who was trying to find a real “presence” by making sense of the show was missing what was so beautiful about it: that it is structured around the eternal deference of presence.

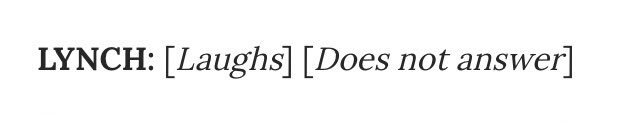

But I finally realized, looking for updated theories, that this image of Twin Peaks specifically and Lynch’s films in general as offering a perpetual deferral was itself founded on a very clear sense of presence: the presence of Lynch himself. It’s Lynch’s personality, his comportment and self-portrayal as mysterious and inscrutable, the way he wriggles out of every question, that holds up the entire system of perpetual deferral.

The Lynch mystique is carefully built to seem unbuilt. We want to believe in him as someone who is not putting on a show, an “all-American Martian boy”, as one critic called him. We are getting the real deal, and it is because we (I should really say I here, but I think I am not the only one who falls into this trap) believe in his sincerity that we can believe in the infinite deferral of explanation and meaning. We can only say we will never get an explanation because we already have an explanation in the presence of what we understand Lynch to be.

The Lynch mystique is carefully built to seem unbuilt. We want to believe in him as someone who is not putting on a show, an “all-American Martian boy”, as one critic called him. We are getting the real deal, and it is because we (I should really say I here, but I think I am not the only one who falls into this trap) believe in his sincerity that we can believe in the infinite deferral of explanation and meaning. We can only say we will never get an explanation because we already have an explanation in the presence of what we understand Lynch to be.

This is all to say: sorry, theory-builders and explanation-hunters, for condescending to you for so long. I was not being the enlightened one, free from a need for definitiveness and clarity, and you were not all the rubes, looking for certainty where there was none to find. What I thought was my disavowal of explanation was actually my secret commitment to it, in the form of the cult of the artist himself.

And in your search for a set of explanations that would make sense of everything, you were the ones risking uncertainty – risking, because uncertainty can always only be a risk. Realizing that there is, right now, a complete lack of certainty may simply be sensible, but being certain that there will never be certainty is just an easy way to trick ourselves.