When bulldozers accidentally hit upon a cache of film reels in the cold ground of Dawson City, deep in the Yukon Territory, it was compared to the discovery of King Tut’s tomb.

Hyperbolic? Maybe. But the find — 533 films “dating from the 1910s and 20s [and mostly] previously unknown to film scholars or thought to be totally lost” — really was something of a miracle. It’s a hell of a story, full of unexpected correspondences, that film-loving experimental documentarian Bill Morrison tells in the Dawson City: Frozen Time.

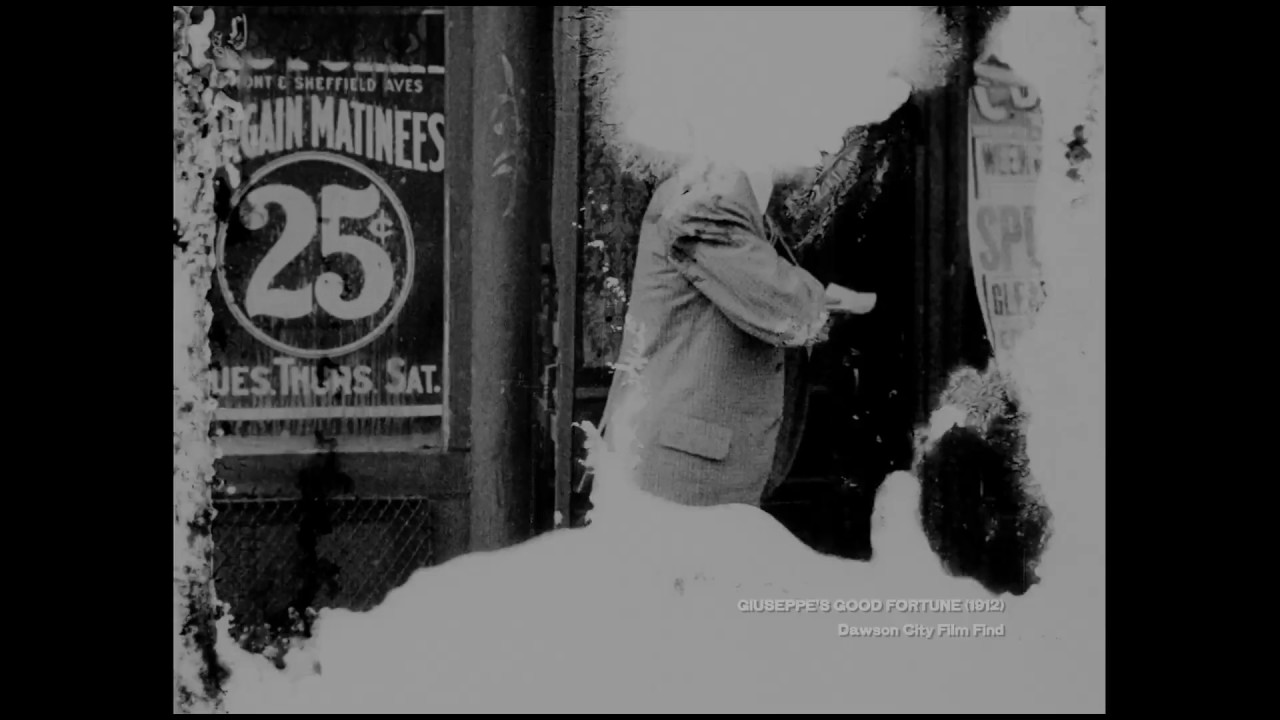

Perhaps “tells” is the wrong word for what Morrison does. Perhaps “documentary” is the wrong word for his film. But here, 500 miles north of Juneau, frozen in the remains of a Gold Rush-era mining town’s rec center swimming pool / hockey rink, at the far outpost of the continent’s most punishing theatrical distribution route, were movies no one knew about or barely remembered, films once screened to the remote thousands now pulled, remarkably preserved, like nuggets from the earth. Morrison shows us clips, provides some context, but the stories are in the images themselves, in their very improbable existence, at the edge of the world.

In this digital era — in which, we imagine at least, nothing ever really vanishes — the degree of silent film obsolescence is hard to process. According to the Library of Congress (PDF):

[T]here are 1,575 titles (14%) surviving as the complete domestic-release version in 35mm. Another 1,174 (11%) are complete, but not the original—they are either a foreign-release version in 35mm or in a 28 or 16mm small-gauge print with less than 35mm image quality. Another 562 titles (5%) are incomplete—missing either a portion of the film or an abridged version. The remaining 70% are believed to be completely lost.

Scholars, historians, and film enthusiasts can be forgiven some hyperbole, then, as far as the Dawson City find is concerned; every discovery’s notable, but more than 500 at once? These are films that everywhere else have literally exploded and burned down the buildings where they were clumsily housed, or tossed out as unprofitable garbage (including, in Dawson City, into the Yukon River), back in the days when the notion of “preserving” something so trivial as a film at all would’ve sounded ludicrous. The primary reason so many reels even remained in Dawson City in the first place is that distributors and studios were unwilling to pay to transport them back.

Scholars, historians, and film enthusiasts can be forgiven some hyperbole, then, as far as the Dawson City find is concerned; every discovery’s notable, but more than 500 at once? These are films that everywhere else have literally exploded and burned down the buildings where they were clumsily housed, or tossed out as unprofitable garbage (including, in Dawson City, into the Yukon River), back in the days when the notion of “preserving” something so trivial as a film at all would’ve sounded ludicrous. The primary reason so many reels even remained in Dawson City in the first place is that distributors and studios were unwilling to pay to transport them back.

Morrison gives us a material history of and through these movies, zooming in on their images and then out, to the worlds they reveal. To Alberto Zambenedetti, Morrison’s work in general is “devoted to the contemplation of ‘ruin beauty.'” As in his landmark Decasia, Dawson City emphasizes impermanence and the volatility of nitrate, with a focus on the uncompromising aesthetics of natural processes that seems like a distant, filmic cousin to other wobbly postmodern forms, like the intentionally deconstructing installations of Andy Goldsworthy.

But there is no sighed so it goes in Morrison’s assemblages, and humans are front and center. The sense of nostalgia and the sorrow of loss are accompanied by a kind of narcotic bliss, a “mysterious allure” in film’s decay, and a strong desire to look closer, to peak behind curtains of time and damage, to uncover secrets, to make connections.

Drawing on Florence Hetzler — who described a ruin as”the disjunctive product of the intrusion of nature upon the human-made without the loss of the unity that our species produced” — Zambenedetti, in his Celluloid Museums (PDF) finds in Morrison an “archeologist of the moving image,” and in Dawson City a “film that uses films to tell the history of film.”

Drawing on Florence Hetzler — who described a ruin as”the disjunctive product of the intrusion of nature upon the human-made without the loss of the unity that our species produced” — Zambenedetti, in his Celluloid Museums (PDF) finds in Morrison an “archeologist of the moving image,” and in Dawson City a “film that uses films to tell the history of film.”

Not just buried film history, though: the unearthed images brought to light here also reveal life as it was lived, along with life as it was reflected back from the multiple screens of this distant Arctic Deadwood. It’s a material history in the most literal sense. The oneiric collisions and correspondences also serve a documentary purpose — we see the gambling halls and the whorehouses (including those that made the Trump family fortune); we see photographic stills that were themselves barely saved from casual destruction, handed down only by the vanishingly unlikely accidents of the world; we see the Gold Rush and The Gold Rush. It’s all so unlikely. As Deborah Eisenberg writes in the New York Times Book Review, the essence of Dawson City is:

echo, paradox, allusion—the lust for gold that drove hundreds of thousands toward the top of the world only to perish; film, the history-altering substance that records, informs, preserves, gives joy, consumes itself, and kills; Dawson City, the town that sprang up on frozen land, flourishing by impoverishing another population; the cyclical catastrophes from which it continued to rebuild itself.

The permafrost in which the reels of film were buried both left its ambiguous marks on the images while also preserving them. (A wonderful story, and preservationist’s nightmare, relates the recollections of Dawson City’s later teenagers, who’d light the edges of film peeking through the hockey rink on fire for fun, a mysterious nitrate flare in a rec center.) It’s one of the key paradoxes informing Dawson City‘s wondrous tale, and, in an offhandedly bemused reflection, archivist Kathy Jones-Gates wonders what else might lie below our feet in the ice of history.

In this case, we won’t have to wait long to find out: while digging up the earth as part of a sewer project just last week, construction crews in Dawson City uncovered a safety deposit box eight meters below ground. Officials are concerned its contents might be hazardous, assuming there’s anything inside; the town’s superintendent of public works is skeptical it’s of any real value; a Yukon government archeologist doesn’t consider the find in and of itself remarkable, though he emphasizes that the stories behind it might be.

We’ll know soon enough. The safe is scheduled to be opened on Discovery Day, August 20th, just over a week from now. Curtis Smoler, “a long-time Dawson resident,” thinks gold would be “the ultimate thing” to find inside, but added, “I hope they find something, even if it’s old documents or old photographs.”

On Twitter, Morrison was more specific: “I’m hoping for more films.”