It’s dumb—I know it’s dumb—but watching The Professional reminded me I have never completely gotten over the strangeness of seeing schlock blockbusters from traditionally art-house countries.

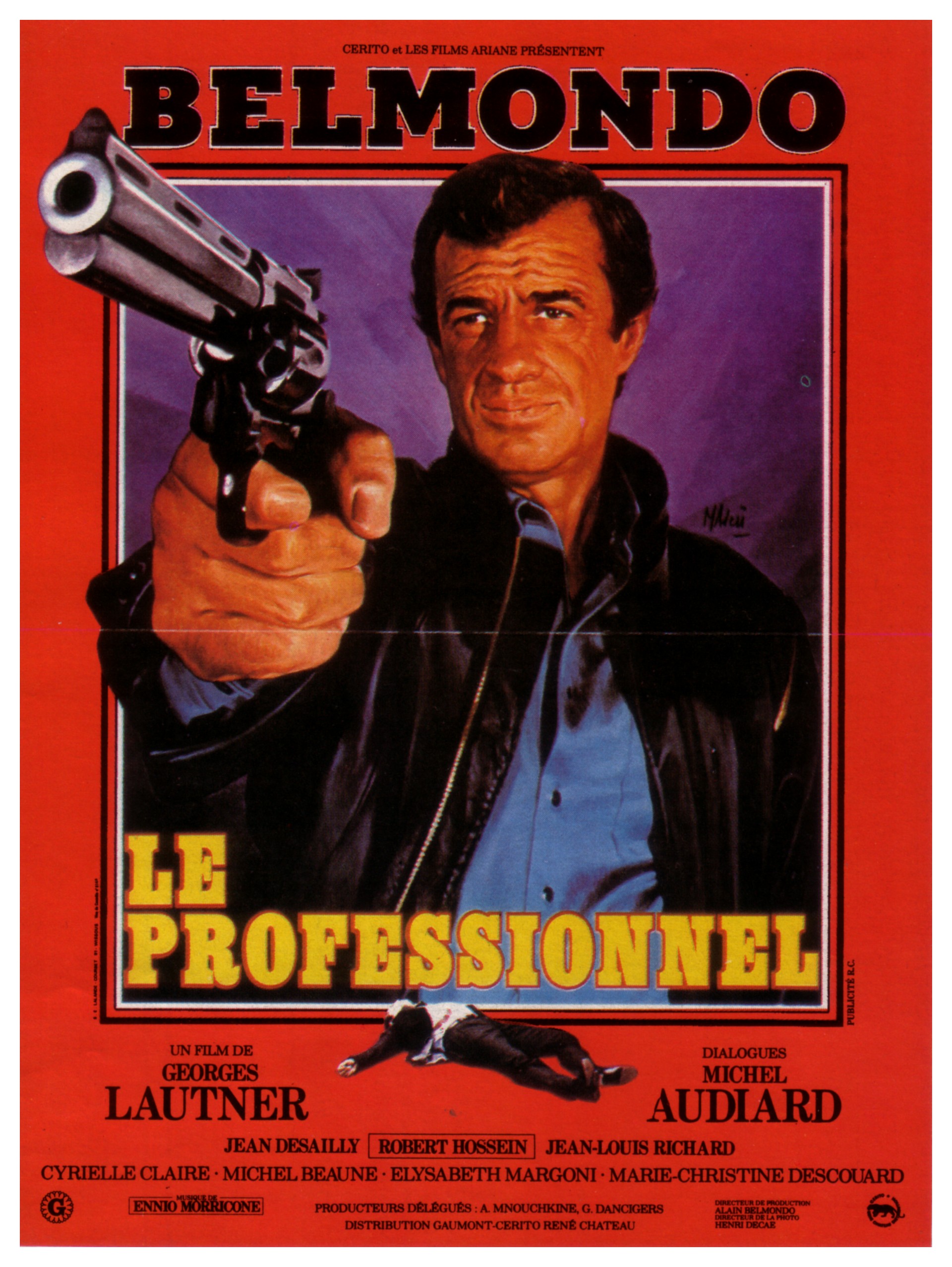

Is that Jean-Paul Belmondo of Breathless and Pierrot le Fou fame offering goofy quips about “kicking ass” and beating up blonde henchmen? (Yes, it is.) Did this really come out of France in the same year Marguerite Duras made Agatha and the Limitless Readings? (Yes, it did.)

B-movies I understand. Exploitation movies I understand. But there is something particularly weird about seeing foreign movies that so clearly ape American rhythms and style. Coming out in 1981, The Professional was on the vanguard of the blockbuster period, let alone its European variant (Raiders of the Lost Ark unsurprisingly beat it in the theaters, but it still sold the fourth-most tickets period that year in France, including among American films). There’s a car chase around the Eiffel Tower (and it’s heartening to know that even French movies feel it is required to use the Eiffel Tower to establish Paris-ness). It’s a weird, goofy mix of 70s Eurospy camp and 80s Rambos I and Part II half-spoiled patriotism.

But what is most interesting about The Professional is one particular trope, which manages to transcend its political particulars. The plot outline has become a mainstay of spy movies: a professional with a steely jaw is on a mission for his country when he is stabbed in the back by weaselly politicians; he survives on gruel in a foreign prison until he escapes and returns, looking for revenge. But it’s the mission itself that’s interesting: Belmondo is sent to knock off the leader of a nameless African country, and when he escapes and returns to France, he makes it his mission to finish the job. (Luckily for the film’s budget, the leader happens to be visiting Paris at the time.)

It was only seeing it in this context, of a France coming to terms with its colonizing past—a past that is finally just past enough that it can return quietly to the cultural unconscious—that this trope made historical sense. The film opens on and luxuriates in Belmondo’s trial, in which the drugged-up white man struggles to stand in a room full of black faces. We see it repeatedly—the government officials who betrayed Belmondo have it on videotape. It’s this moment of embarrassment before a trial, rather than the torture that follows, that the movie focuses on as the source of deepest betrayal.

That moment is only possible in a world where former colonies can claim themselves to be political equals to their former oppressors. The entire scenario is inseparable from the world of the United Nations and of the Hague. The fear that those of “us” in the colonizer’s country can now be judged by their laws is the motivating anxiety that generates this world.

The fear of the judging gaze (both legally and psychologically judging) is a variant of the “wrongfully imprisoned man” movie that is more popular in the U.S. Someone goes to jail for something they didn’t do, breaks out, finds the killer, et cetera et cetera, with The Fugitive being the modern touchstone. There, a plot revolving around the exception (what if our justice system fails, and an innocent person is imprisoned?) serves to buttress the system itself (if you’re innocent, you’ll find a way to escape and everything will be worked out—the modern version of the trial by combat).

In The Professional, the rule (what if all the rhetoric is true, that people will be judged for their colonialist actions, that we will actually have to begin treating these countries as equals?) serves to undermine the system (don’t worry, they’re not powerful enough to keep our soldiers down; their claims of justice will fail because of our inherent superiority).

And within this context, the rather cliché finale takes on a new dimension. Belmondo finally tracks down his target and tricks the French government into killing him (he manages to get him to pick up an empty gun in front of a window at the perfect angle—listen, this isn’t a good movie). It’s curious because it testifies to the ambivalence the filmmakers feel towards their structure of justice. The hero can’t simply murder in cold blood; instead, he manages to get the official forces of justice to kill the “right” person, the target deigned moral by the logic of the film, instead of their actual target, the “wrong man” of our hero assassin.

It’s a short circuit, in a way: the circuit of a universal justice is recreated. They manage to return to a colonialist logic of the virtuous forces of civilization executing the villainous forces of foreign self-ruling despotism; but, at the same time, this can only be done by tacitly admitting that this is something immoral that the government can’t do, that it’s only by a trick that this happens—in other words, the dominance of colonialist France over its former colonies is both reduced to and elevated to a cosmic element of reality.

There’s a lot to say about how the spy genre has addressed and absorbed rhetorical discourse about international law and national sovereignty. I definitely am not qualified to write that history, as much as I would like to. At the very least, though, it is remarkable how watching spy movies with that lens in mind can make explicit so much subtext, even in the stupidest of movies.