In a press conference at the Venice Film Festival, Philippe Garrel once remarked, “Given that nowadays in France, there is a tendency to forget 1968, to erase it from the map of history, I thought it would be useful to raise the question ‘what is cinema for?’ And I thought it was useful for this film to bear witness to some things.” He was speaking of Regular Lovers, his woozy 2005 narcotic dream of the May barricades’ long shadows, but insofar as Garrel’s question touches on cinematic memory itself, he may as well have had 1990’s Dennis Hopper / Kiefer Sutherland comedy Flashback in mind.

He didn’t, of course, have Flashback in mind, because Flashback is forgettable in every way. “If you remember the ’60s, you weren’t there,” someone’s dad once said, and Flashback takes this moldy oldie of a joke at its word. Later, we’ll consider the ways historical memory functions in three respectable, or at least respected, films — Lovers, Bertolucci’s The Dreamers, and Olivier Assayas‘ Après mai — but we start with the clichéd tropes of a more American engagement.

Flashback is vaguely in the Midnight Run mold, another anti-buddy road-trip film that came out two years prior and was distinguished, on the whole, by being enjoyable and clever rather than irritating and hackneyed. (Midnight Run also had the advantage of being competently directed by Beverly Hills Cop‘s Martin Brest rather than Franco Amurri, whose only other U.S. directing credit starred Harvey Keitel, a young Thora Birch, and an escaped capuchin monkey named Dodger who steals people’s wallets.) Agent John Buckner (Sutherland), an ambitious federal up-and-comer with a deep-seated distaste for rabblerousers, is tasked with escorting captured-at-last Yippie Huey Walker (Hopper) to prison, finally doing time for a stunt back in ’68 in which he embarrassed both the FBI and then-VP Spiro Agnew. Some canceled flights, rail hijinks, acid trips, bloodthirsty sheriffs, mistaken identities, bickering bouts, and far-out needledrops later, John and Huey will come to see each other in different lights.

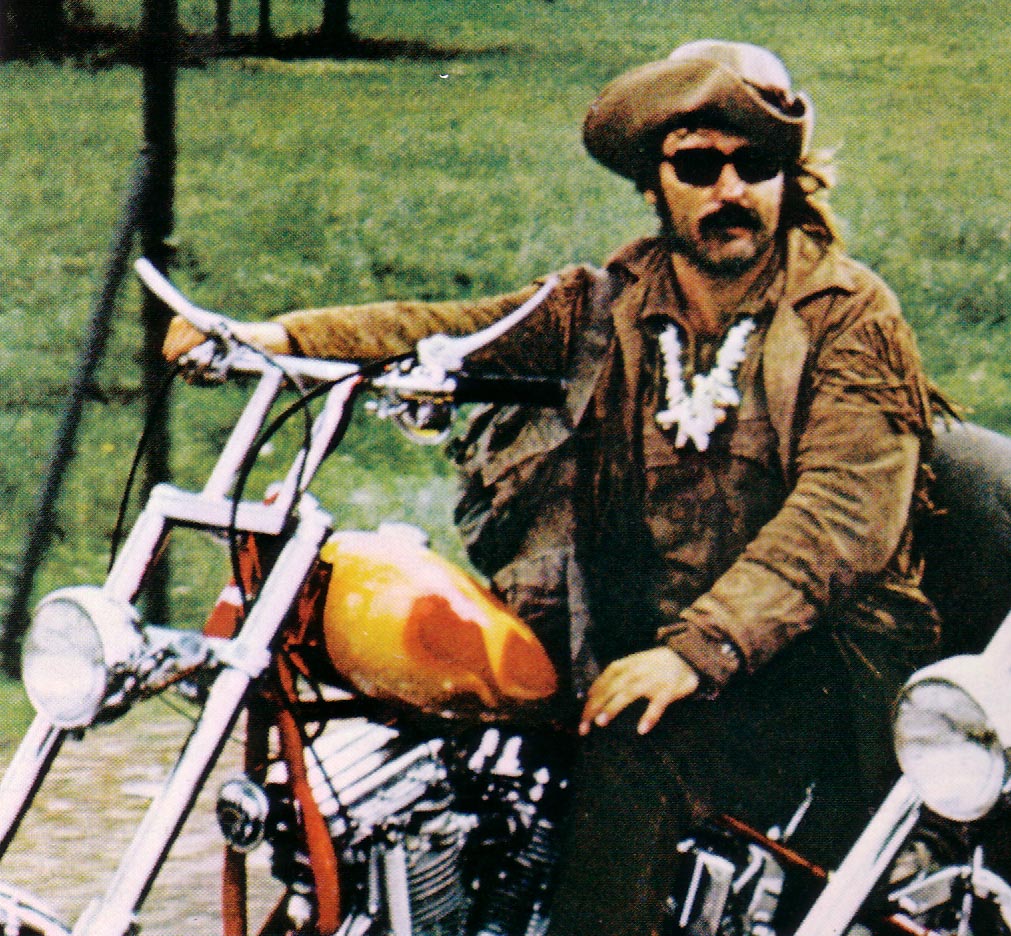

This is, of course, very boring, but what is interesting about Flashback is the way it remembers, the specific forms of cinematic citation it deploys for contemporary meaning. Hopper is the central focus here precisely because he is himself an icon of the late ’60s, and his every gesture and Dennis Hopperism reminds us of this. Lest we forget his acid auteur status, Huey even compares their trip to Easy Rider, and Born To Be Wild plays not once but twice. (It’s funnier the second time, but only because you can’t believe they’re doing it again.)

This is, of course, very boring, but what is interesting about Flashback is the way it remembers, the specific forms of cinematic citation it deploys for contemporary meaning. Hopper is the central focus here precisely because he is himself an icon of the late ’60s, and his every gesture and Dennis Hopperism reminds us of this. Lest we forget his acid auteur status, Huey even compares their trip to Easy Rider, and Born To Be Wild plays not once but twice. (It’s funnier the second time, but only because you can’t believe they’re doing it again.)

These direct invocations allow that 1969 touchstone to be easily grasped and presented ironically, and we can begin to read Flashback‘s conservative thesis. In the narrative, this takes the form of a reveal: we discover that Huey was both a fraud — he never succeeded in detaching the train car that embarrassed Agnew; it happened despite his efforts, but he took the prankster credit — and something of a folk hero inspiration in ways he himself, blinded by anxious glory, hadn’t truly appreciated. (The real Easy Rider was love.) Meanwhile, it turns out that straight arrow Sutherland was raised on a commune — his real name is, ahem, Free — and has gone to a fascist extreme to distance himself from his hippie parents, losing much along the way. (Flashback draws a somewhat bafflingly direct line from childhood embarrassment over eating alfalfa sprouts to a career in law enforcement intelligence, but at least there are no pickpocket capuchin monkeys, I guess.)

But there are two varieties of memory at work, and at odds, in Flashback: the Steppenwolf reveries of Hopper’s long-in-the-tooth activist and Sutherland’s old-before-his-time G-Man repression. Both are fundamentally cinematic in nature.

Commenting on Bertolucci and 1968, Michael Leonard speaks of his use of past cinema citation as “intrinsically conservative — reactionary even — implying a historical linearity that evokes the ‘pastness’ … and its significance as a piece of heritage rather than as part of an ongoing historical process or dialectic.” Interestingly, Flashback tries, and fails, to find a way around this in the Hopper character: the Easy Rider callbacks may be groan-inducing, but aim to function as a cracked mirror, an ironic engagement with an unfixed past that still has consequences, even if that consequence is mostly Hopper’s rebirth as a capitalist trickster. Flashback‘s Hollywood approach, its surface sheen and jaunty narrative beat, undoes anything that might challenge our assumptions; that the central citation arrives in the non-diegetic soundtrack only provides a joke for the viewer, and not a very good joke at that. Get your motor runnin’ … The characters simply move through indifferently framed story arcs, with the possibility of growth frozen in referential cliché, out of their earshot.

Commenting on Bertolucci and 1968, Michael Leonard speaks of his use of past cinema citation as “intrinsically conservative — reactionary even — implying a historical linearity that evokes the ‘pastness’ … and its significance as a piece of heritage rather than as part of an ongoing historical process or dialectic.” Interestingly, Flashback tries, and fails, to find a way around this in the Hopper character: the Easy Rider callbacks may be groan-inducing, but aim to function as a cracked mirror, an ironic engagement with an unfixed past that still has consequences, even if that consequence is mostly Hopper’s rebirth as a capitalist trickster. Flashback‘s Hollywood approach, its surface sheen and jaunty narrative beat, undoes anything that might challenge our assumptions; that the central citation arrives in the non-diegetic soundtrack only provides a joke for the viewer, and not a very good joke at that. Get your motor runnin’ … The characters simply move through indifferently framed story arcs, with the possibility of growth frozen in referential cliché, out of their earshot.

Sutherland’s encounter with footage of his own past, on the other hand, briefly indicates a different tack, one that Flashback has little interest in pursuing. Sitting on a couch in the abandoned commune, its lone, free-spirit resident (Kane) screens scoreless fragments of Sutherland’s youth, kids and family still playing in the gauzy Super-8 fields of the Summer of Love.

That our memories are not just of cinema but in cinema is a historically new phenomenon: we remember by and through treatments, time-bound image captures, full of movement and color, that are never really static. Created with one intent, perhaps, the movies of our lives are transmuted with every viewing, filled with the detail of dreams. Hopper’s character does “reinvent himself” in Flashback, surfacing from a fake death with all of the citations scrambled, climbing into a limo rather than hopping on a bike full of cocaine and American wanderlust. But it’s a retreat into cinema, wobbly and hokey and fleet, like a capuchin monkey stealing your wallet. When Sutherland watches the movie of himself, it’s important only to the degree that the image bank of history itself is as warped by his viewing as he is by the images flickering back.

Then we get on the Magic Bus with Carol Kane and the rest of Flashback‘s happy horseshit bounces to its expected conclusion. But even in forgettable detritus like this, we see cinema’s drive to remember.