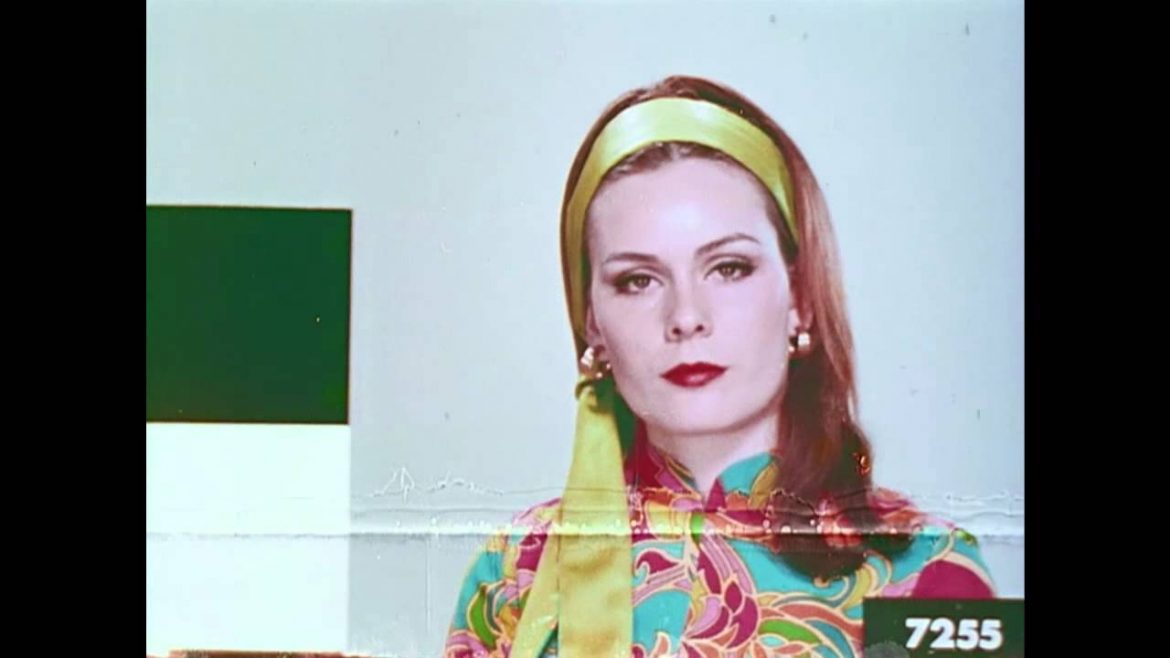

Like many people in the post-cinema age, I suspect, I first encountered them in the closing sequence of Quentin Tarantino‘s Death Proof: Leader Ladies – or Shirley Cards, or in the off-puttingly Orientalist language by which they’re more traditionally known, China Girls. They close out Tarantino’s contribution to the film-nostalgic double-feature Grindhouse, flashing one after another between the credits in the sort of anachronistic pastiche flourish for which the director is known.

And like many viewers, I wasn’t quite sure what to make of them at the time. “OK,” begins a May 2007 post on the Tarantino Archives Forum, a month after the film’s release, “please don’t laugh at me because I honestly don’t know who these chicks are.” Commenters offer up theories on these “subliminal women” and what they’re “supposed to mean”: “I didn’t recognize them as movie actresses though. They just looked like models from 70’s fashion magazines.” “Maybe the photos are of women in his life like his mom or Sally Menke (spelling?)” “I have no idea what you’re talking about.”

Eventually, some nerd by the name of Raptor steps in: “The images in the end credits are known as Shirley cards. When professionally processing film and prints, the company that produces the equipment and chemistry provides perfectly exposed, but unprocessed film and print tests, along with a copy that has been properly processed. You process one of the pre-exposed tests, then compare it to the control print to make sure everything looks as it should.”

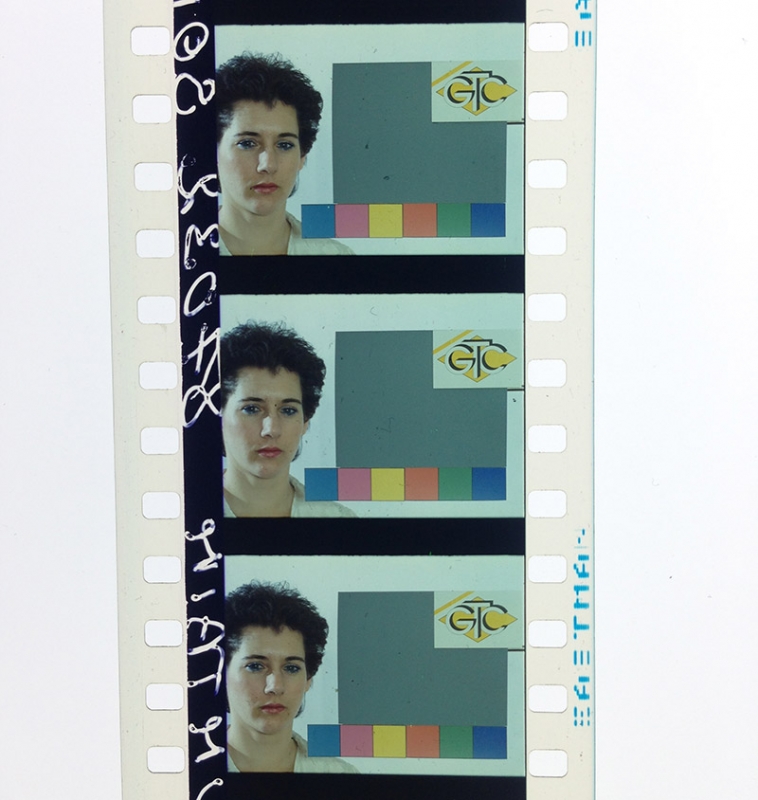

That nerd was right. As the Harvard Film Conservation Library writes, using a different term for the women depicted, “China Girls have been used since at least the 1920s in color or density test frames made by labs to assure standardization of print quality.”

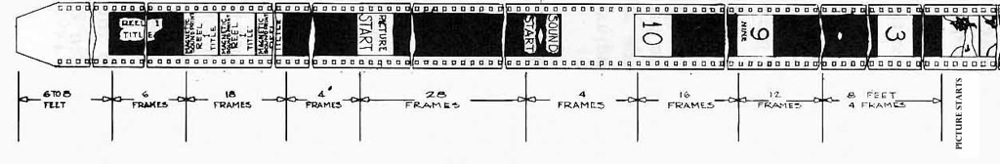

Via the Chicago Film Society (https://www.chicagofilmsociety.org/projects/leaderladies/): “Here is a diagram of typical film head leader. “China Girls” usually appear somewhere between the “10” and the “3” shown in the countdown below (though they appear elsewhere as well).”

But as Genevieve Yue exhaustively demonstrates in The China Girl on the Margins of Film, this only scratches the surface of a fascinating history and attendant discourse. Appropriately enough, Tarantino’s use of the images primarily serves – like the assemblage’s double-feature structure, de rigeur sprocket holes, continuity glitches, and parody intermission – to mark Grindhouse as a film pastiche about surfaces (surface pleasures, the gleaming techno-surfaces of cars and guns, the tactile surfaces of film): lovingly constructed but flat, ironic, without a future. The film, and its fragmentary closing images, are proof enough of some kind of death. (That the credits are set to April March’s “Chick Habit” – an English-language reworking of the Serge Gainsbourg-penned “Laisse tomber les filles” that somehow sounds more like a ye-ye anthem than the original – only increases this hauntological sense that “the time is out of joint”.)

That futurelessness feels baked into the untethered stills, which, given their intended use as calibration tools, seem unstuck in time. But they exceed this instrumental use. They push back against it, in part because they are also snapshots of actual women, often lab workers, at particular historical moments, in service to specific technologies that necessitated both their presence as leader and their absence from the “film itself”. If, in the meta-text of Tarantino’s Death Proof, they function as symbolic time-stamps and ironic punctuation marks, R. F. Hall of the Chicago Film Society points out that they also represent:

a fleeting visual document of the film industry’s vast off-screen labor pool. They remind us that every film made on film stock has a physical history, that each print we encounter in the projection booth, or projected onto the screen from the audience (or reproduced digitally on a laptop screen) passed through the hands of lab workers and technicians before it came to us.

That embodied material history also colors how we receive them: the China Girl is at once utterly grounded in real proximity to the modes of production, necessitated by its technological dictates, and in excess of that context, evocative but vulnerable to the demands of viewership, too. As Vivian Sobchack writes, “technology is never merely used, never simply instrumental. It is always also incorporated and lived by the human beings who create and engage it within a structure of meanings and metaphors in which subject-object relations are not only cooperative and co-constitutive but are also dynamic and reversible.”

Even her nomenclature — “China Girl” — arrives overdetermined and fraught. The origin and intention of the term is itself a matter of debate, as the Chicago Film Society (which hosts a fascinating collection) explains:

One popular theory connects the term to a “Chinese-style” garment (most often a colorful shirt) worn by the model in some test frames. Another suggests that early test frames used porcelain (“china”) mannequins instead of live women. Regardless of origin, “china girl” is by far the most common American term for them. (Others recorded include “lady wedge”, “china doll”, “girl head”, and “leader lady”). In France, they’re called “Lili,” perhaps after the traditional name of the slate used in Technicolor shoots.

Regardless, what Death Proof does do with these images is precisely what they’re not intended for: it shows them. As Yue points out:

Film viewers do not typically see the China Girl. In any given reel of a commercially produced 16mm or 35mm film, three to six China Girl frames are usually cut into the countdown leader, normally between the numbers 10 and 3. Yet this part of the filmstrip is not meant to be projected. The only way a China Girl may be glimpsed in a theater would be if a projectionist failed to switch reels at the correct time, allowing the ends of the film to run out. Even then, the short duration of the China Girl’s appearance would be just as easy to miss, lost in the blink of an eye.

That mysterious ephemerality is part of their appeal, an ephemerality mirrored by the technology of film itself.

All images carry a sense of the ghostly; how much more so by these blink-and-you’ll-miss them splices of screen tests, captured in a long-ago moment and transported, utterly without context, into very different aesthetic surroundings.

All images carry a sense of the ghostly; how much more so by these blink-and-you’ll-miss them splices of screen tests, captured in a long-ago moment and transported, utterly without context, into very different aesthetic surroundings.

These are liminal images in the truest sense, straddling the borders of the film object even as they physically occupy its literal margins. For me, there’s something of a spooky, hushed thrill about her mode of presence — the ghostly, the secret, the buried, the returned. It’s hard not to lapse into a preacher’s cadences. China Girls seem not far removed from any number of art objects found buried in film canisters in the Yukon, written in the margins of illuminated manuscripts, found scrawled on Michaelangelo’s Florence prison walls or coded in invisible UV paint inside Basquiats — a kind of art behind the art. It’s, in some basic way, a desire for the revealed word, but it’s also the object of desire for archivists, detectives, people who look.

What distinguishes the China Girl is that the Word should be a Face, and that this looked-upon object should be so intrinsically hard to grasp. Unlike the Warhol screen tests, for instance, or the face of Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc — faces we are meant to study for “lies that tell the truth” or gaze into like oceans of feeling — the face of the China Girl is structurally obscured. Rather than a “reveal[ing] an invisible face within that of an actor,” Yue posits, “the China Girl that appears behind the scenes figures a different kind of invisible face, one that speaks to a film’s most fundamental conditions of visibility.” She is:

positioned differently in relation to the faces onscreen: She is not the invisible other buried within the visible image but something that remains outside the field of vision afforded by the screen. Though China Girls are on rare occasions produced for individual films, their production and usage exist independently of the films to which they are spliced. A China Girl can thus accompany any number of films, and in some cases, especially with restored or duplicated films, several different China Girls can accumulate on the same strip of leader, artifacts from different laboratory processes. From the perspective of viewers who are mostly unaware of her existence, the China Girl structures an absence, and an imperceptible one at that. She is an extreme manifestation of what the suture seeks to exclude, though she is no less critical in determining cinema’s system of representation as, following Laura Mulvey, a gendered construct.

So here we have ghostly presences, highly gendered and Othered, that offer inroads to the material, embodied processes by which the technologies (the essences of which are never technological) shape and structure our relation to the world. Given the currents of modern scholarship, with its highly instructive emphasis on the marginal and overlooked, on the vast army of women vanished from the history of aesthetics and their material production, China Girls are worthy of increased attention outside cinephilic circles.

“The face resists possession, resists my powers,” Levinas wrote; “[it] speaks to me and thereby invites me to a relation.” But that relation is here fixed in time, even in the context of otherwise moving pictures, the fundamental aspect of which is their need for constantly “coming-into-being”: the China Girl becomes an appropriable representation, more like the photograph that functions as

a ‘being-that-has been’ (a presence in a present that is always past). Thus, and paradoxically, as it materializes, objectifies, and preserves in its acts of possession, the photographic has something to do with loss, with pastness, and with death, its meanings and value intimately bound within the structure and aesthetic and ethical investments of nostalgia.

Even in the transition to the electronic and to post-cinema, she has remained just off-screen, enjoying a cult of her own among film enthusiasts — a cult without agency, of course, despite the occasional efforts of experimental filmmakers to offer her a way out. The obstinacy of her haunting seems odd because she’s clearly outlived her technical usefulness, but this is also how we know that she says more about our relationship to image-making and image-owning:

As a face, however, the China Girl suggests something more, an attachment that approaches a kind of pathos or sentimentality, which is evident in the many private collections of clipped China Girl frames. As film facilities shrink or shut down, the China Girl has become one of the more poignant symbols of an outmoded industrial model in an era of profound technological change. Its ephemerality, the anonymity of the women who posed as models, the abstractions and rare mentions of the image in industrial manuals, and the literally marginal position the figure occupies in relation to the history of cinema may be, somewhat ironically, the traits that best express a sense of nostalgia for a vanishing medium.

The China Girl’s unique position is characterized by multifold hybridity: it is a photographic construct deployed for the needs of the cinematic that assumes, as a set of free-floating copies increasingly distant from any notion of an “original,” a range of new senses and affect in the electronic. Her encounter — for instance in Death Proof — is a case study in the ways in which “[N]arrative, history, and a centered (and central) investment in the human lived body and its mortality become atomized and dispersed across a system that constitutes temporality not as a coherent flow of mordantly conscious experience but as the eruption of ephemeral desire and the transmission of random, unevaluated, and endless information.” She, and we, are unstuck. The time remains perpetually out of joint.