Given that seemingly every day brings with it a new and horrifying perspective on America’s descent into Trumpian doublethink, it can be hard to keep track. It’s not just the outrage cycle, either – we really are living through uniquely dismal times; if the moral affronts aren’t necessarily new, the attitudes towards them, ranging from casual disregard to gleeful celebration, sure seem to be. The recent “border incident” revelations about our government separating children from their parents marks the newest low in state terrorism masquerading as refugee adjudication policy, a sustained attack on mercy and grace so repugnant that the even this president – a nativist rapist who has rarely encountered a sin he couldn’t instinctively market as a discount virtue – can’t quite bring himself to boast about it.

The shame itself is familiar and enduring, part and parcel of America’s long, ignoble tradition of celebrating the vaunted idea of the immigrant nation while loathing the flesh and blood immigrant herself; a lamp lifted by the golden door like a spotlight, the better to identify, detain, and expel. It’s not for nothing that we say the immigrant workforce labors in shadow.

Still, like most things Trumpian, a new sense of shamelessness animates the nativism. Watching Anthony Mann‘s daytime noir Border Incident (1949), it’s hard to ignore the degree to which attitudes have shifted and calcified, how much we have hardened our hearts over the course of 70 years. Usually, we watch old movies through a lens of progressivism: we are bemused by antiquated attitudes, or outraged, but generally celebrate our slow, steady march to widening justice, an incremental righteousness that these historic relics exist to affirm; we were once much worse to each other, and we shall be better still. In current lights, Border Incident — one of the very few, perhaps only, film focused on the bracero program — plays like an accusation to the contrary.

Like Mann’s Raw Deal and T-Men from the previous two years, Border Incident is a procedural, a hard-boiled “composite case” that explicitly presents itself as a celebration of government workers, doing dangerous jobs for the common good. These films invoke a semi-documentary aesthetic, complete with an introductory scene assuring us that the fictionalized accounts are grounded in approved fact, presented with the government’s imprimatur. They are earnest and forthright, hilariously so for the earlier B-movies: T-Men‘s exuberant celebration of the “five fingers that form the fist” of the Treasury Department, which “hits hard, but hits fair,” has the ring of a bureaucratic kung-fu flick; you expect hooded accountants scaling cubicle walls, but mostly get a convoluted undercover narrative about counterfeiters.

Like Mann’s Raw Deal and T-Men from the previous two years, Border Incident is a procedural, a hard-boiled “composite case” that explicitly presents itself as a celebration of government workers, doing dangerous jobs for the common good. These films invoke a semi-documentary aesthetic, complete with an introductory scene assuring us that the fictionalized accounts are grounded in approved fact, presented with the government’s imprimatur. They are earnest and forthright, hilariously so for the earlier B-movies: T-Men‘s exuberant celebration of the “five fingers that form the fist” of the Treasury Department, which “hits hard, but hits fair,” has the ring of a bureaucratic kung-fu flick; you expect hooded accountants scaling cubicle walls, but mostly get a convoluted undercover narrative about counterfeiters.

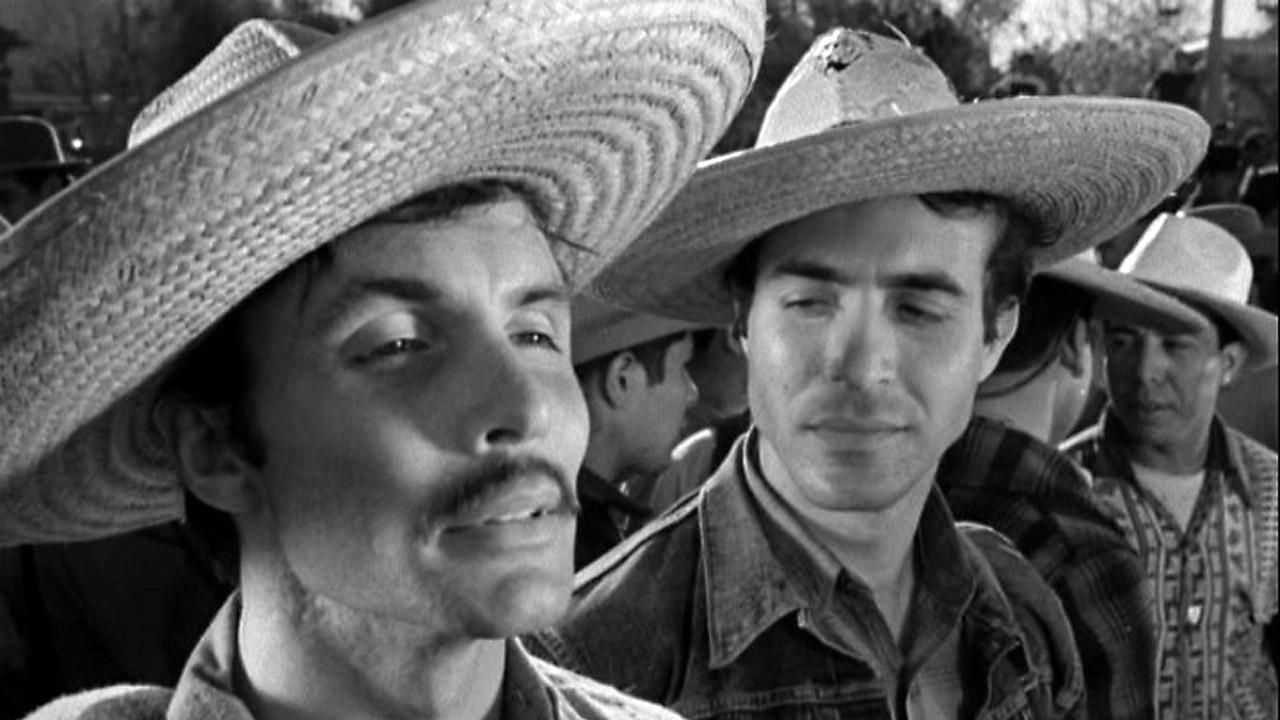

Border Incident is a much less ludicrous affair, with a clearer if similarly-minded story arc and a definite budget assist from the move to MGM. All three films mentioned were shot by John Alton, with inky impressionist palettes and an eye for the startling death scene, but Border Incident‘s top-tier resources make the most of his skill, well-matched to Mann’s no-nonsense muscularity. Ricardo Montalban, seeking to escape from typecast exoticism, plays a compassionate Mexican lawman; future Republican Senator George Murphy is his American counterpart. The two go undercover to break up the gangster stranglehold that squeezes desperate workers on both sides of the border.

The implicit Leftism of this construction is hard to miss, barely concealed by the paeans to patriotism and the stamp of approval. What’s interesting, from a viewpoint under daily assault by the Trump administration’s venality, is how clearly compassion and justice feed a country’s self-image: there’s no contradiction here. It is a marker of patriotism, of American (and Mexican) greatness, that our protagonists care about the downtrodden.

The implicit Leftism of this construction is hard to miss, barely concealed by the paeans to patriotism and the stamp of approval. What’s interesting, from a viewpoint under daily assault by the Trump administration’s venality, is how clearly compassion and justice feed a country’s self-image: there’s no contradiction here. It is a marker of patriotism, of American (and Mexican) greatness, that our protagonists care about the downtrodden.

Immigrants, even those driven by circumstance to operate outside the law, are treated as striving and fundamentally noble in their values, seeking a better life for their families. Border Incident never considers it any other way. Of course, the agents of the law think they should “play by the rules,” but recognizes without hesitation that the game is rigged, and men (sic) will do what they must. All of Border Incident‘s outrage is reserved for those who would traffic them, amoral opportunists who describe human beings in the language of commodities, skimming money or prestige from misery all along the way.

This sense of compassion extends from narrative to Mann’s mise-en-scene: as Adrian Danks writes, “We do not enter the seamy, endlessly crisscrossed, inherently noir or fluid border world we have become familiar with through such films as Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958).” This is not a metaphysical space (and Mann, to his enduring credit, does not slap a greasy mustache on Charlton Heston). The world of Border Incident is relentlessly material, a ruthless distillation of capitalism and its discontents:

The border does not throw up a hybrid culture and geography, a schizophrenic melange of disenfranchised and displaced individuals, but operates instead as a “cattle-run” to be exploited by whoever occupies the high ground… The difference between the two cultures here is more a matter of inequitable economies and different stages of development than soft underbellies (and softness is not a quality generally characteristic of Mann’s cinema). The difference becomes a matter of “sophistication” and scale: throat-slashing bandits, smugglers and counterfeiters on the Mexico-side, the technologically streamlined, mass-manpowered machine of exploitation on the US-side. In fact, the film goes out of its way to be even-handed, promoting collaboration, procedure, and personal sacrifice as self-consciously foregrounded solutions to what are actually more ingrained and substantive problems.

The naïveté of that even-handedness, partly a Code-bound concession to the norms of Hollywood storytelling, still stands in dramatic contrast to where we find ourselves now.

Border Incident is remarkable for foregrounding class, race, and immigration status in 1949, but it’s also remarkably insistent that compassion and fairness are defining national traits. Mann’s film is “quaint,” a term usually reserved for queasy period depictions of copious day-drinking, rigid gender norms, and casual racism. (Is there a less racist film in the noir archives?) But Border Incident‘s quaintness lies mostly in its belief that American greatness is predicated on pursuing justice for the desperate immigrant and exploited worker. However papered over by appeals to dual nationalism, it’s a greatness rooted in solidarity.

This is not the greatness to which we are returning.