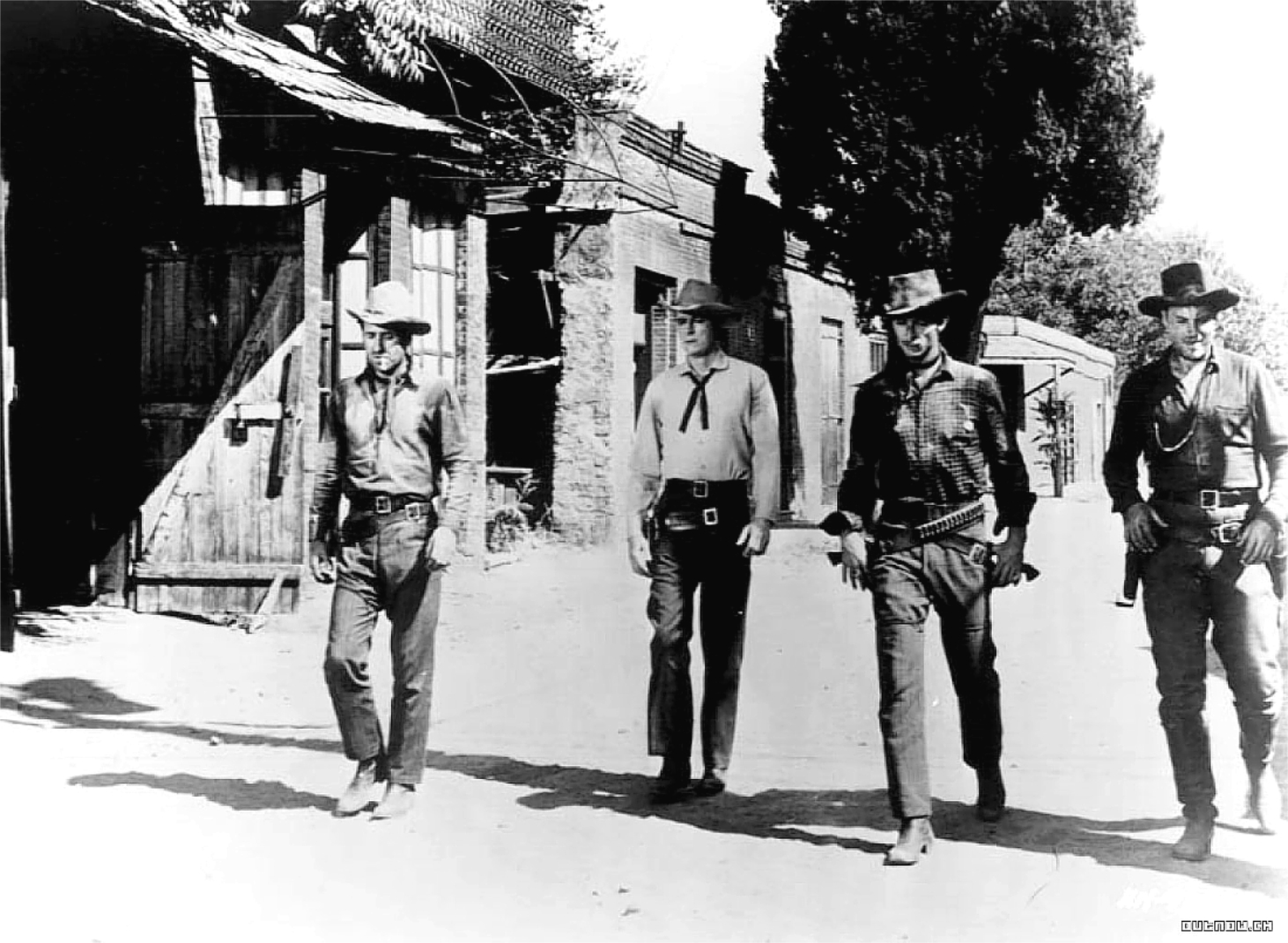

A stranger comes to town with a mysterious past. He’s looking for someone, a Japanese farmer named Komoko, but no one will tell him anything; it’s clear the name brings up dark memories. Some details about him come out: he’s a veteran of World War II, which had recently ended; he’s there to deliver a medal to the father of someone who died saving his life; and he can do karate. And in turn, the secrets of the town dribble out: The father was murdered by the gang that not only runs the town, but seems to be the entirety of its inhabitants, in a fury after Pearl Harbor, and they’re waiting for nightfall to kill him so it doesn’t come out. Well, night falls, guns are fired, and the hero escapes to spread the truth to the world. That’s the thrust of Bad Day at Black Rock, a remarkable example of the Efficient Genre Picture of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

It’s a peculiar mix of film noir and Western – perhaps the only film noir to be shot in widescreen and in gaudy full color. As a little puzzlebox of narrative, building on the inherent propulsive push of the diurnal cycle, it simply works wonderfully.

And that is an interesting word to use here: works. I hear few themes pop up more often in modern film dork culture than the praise of the efficient genre film. These films are the purest form of that old doctrine of screenwriting, that one should get the hero up a tree, throw rocks at him, then get him down. They are almost Aristotelian in form, with a focus on those events that take place over the wonderfully fertile time range between the completely real time and a day/night cycle (with denouement a little after daybreak).

Often this drive for the film that is efficiently plotted internally is wrapped up with a desire for movies to be shorter externally. Listen, I get it: movies are too long. But it is too easy to conflate these two ideas together.

There are a lot of things at play in this drive for the efficient movie, but I would like to suggest a particular reason for its popularity: that it shrinks the size for “themes,” crudely defined, or political aspects, broadly defined. With smaller and smaller scopes, it feels more like the films are “un-thinkpiece-able”. We feel free from the specter of liking something problematic. (No matter how many articles I am shown, I don’t think I’ll ever be convinced that it is as easy as saying it is OK to like “problematic” things, and to have it left at that.)

To circle back around to Bad Day at Black Rock:

It was halfway through the viewing experience that I took a bathroom break, and was flipping through the Trivia tab for the film. That was when I learned a bit that completely interrupted my viewing: that Bad Day was one of the most played films at the White House theater.

OK, it’s insane. It shouldn’t have bothered me. I get it. It’s not a very good film critic-y thing to do. But at that moment I felt a different kind of specter float into the room and hang between me and the TV, Max Cady-style, laughing too loudly at any jokes, cheering too loudly at any successes. I learned later that it was JFK in particular who loved the movie and drove up its view count, but the one that was haunting me wasn’t any particular president. It was an amalgam of them all. It was whatever original person that Aaron Eckhart, Morgan Freeman, and the guy from the Allstate commercials all copied from. It wasn’t a president – it was The President.

I suppose I try to suppress my desire to view every movie politically. After all, at that point it becomes extremely hard to avoid making a value judgment based on its politics, which would cut us off from so much wonderful art in our history. And yet, and yet, as I sat there watching this purely efficient film, a film that just works, I was stuck ruminating on how that idea and the political are so intertwined.

I suppose I try to suppress my desire to view every movie politically. After all, at that point it becomes extremely hard to avoid making a value judgment based on its politics, which would cut us off from so much wonderful art in our history. And yet, and yet, as I sat there watching this purely efficient film, a film that just works, I was stuck ruminating on how that idea and the political are so intertwined.

After all, so many of these ideas of narrative efficiency go straight back to Aristotle’s Poetics, and those standards Aristotle put together were explicitly politically normed. Those rules made good plays, and good plays made a good civilization.

And it is exactly that idea, that the efficiently-made film plays into a healthy civilization however defined, that was brought out by the President as a viewing b buddy. It made me think of another wholly efficient film, one that shares a lot of similarities with Bad Day: High Noon. High Noon is an easy film to see politically, at least for me.

It’s nothing else than a creation myth for the family, an explanation for how the elemental Father can turn from his duty to the city as a whole to the specific duty to his family. It is a narrative that attempts to resolve a recurrent tension in America’s moral systems, the idea that the duty of the family and the duty of the polity feed into one another – and the implicit question of how to choose between them. And in attempting to resolve that tension, it merely makes it more explicit.

Bad Day at Black Rock is in many ways an inverted version of High Noon in a number of ways. One of the most obvious inversions is in the final moment. In High Noon, the protagonist throws his badge to the ground in contempt for the town he defended. In Bad Day, the protagonist gives the medal he came to town to deliver to the murdered Japanese farmer to the town in general, to begin rebuilding. Like High Noon – and, in a way, like the tragedies Aristotle described – it acts out on a small stage the restitution of and foundation of justice (for justice is never founded for the first time; it is always rediscovered and re-founded, always promising a fresh start and a just society).

And what’s wrong with that? After all, justice is less a political “theme” per se than merely the form of the narrative itself. Justice is a story: crime and punishment. Its recurrence in these efficient genre pictures doesn’t make them political, as much as it makes them simply more efficient.

All that is true. But I can’t help thinking, as the President watches Bad Day with me, cheering to the new foundation of the town at the end, what will happen to Komoko’s land. The Japanese farmer was murdered, among other reasons, for not being tricked. The head of the gang sold him land that was supposed to be dry and desolate, but he drilled down far enough to start a well; it was that that truly led to his death.

And what happens to the land now? The gang has been punished for their murder, and the town promises to start again in justice – but what happens to the well he discovered? It will, presumably, become incorporated into the town, or become some new property. In other words, for all the declaration of a new start, the success and health of that new start is reliant on the sins of the past.

And maybe — and this is definitely a maybe — that points to part of the appeal of these movies, where everything wraps up perfectly at the end. There is a sense of a “blank slate” as justice returns, and in that justice the sins of the past can be ignored without any lingering effects. It’s by ignoring pesky questions like what happens to his land that the films remain unpolitical. It allows us to return to the one uncomplicated place: the healed city, just after the cowboy leaves.