Here are Greatest Movie Characters entries 11-20. First part is here. This is not a ranked list, and the ones below are entered in alphabetical order.

11) Clarice Starling (Silence of the Lambs)

Anthony Hopkins might get the acclaim for his delightfully twisted turn as Hannibal Lector in Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs, but it’s Jodie Foster’s Clarice Starling that makes it work. In mostly small moments, and often just by the context or flickers of guarded emotion on her face, we realize just how stranded she is, in the man’s world of the FBI, in terms of class and her own shame of her “white trash” roots, and in her desire to prove herself, maybe to herself. Foster conveys Clarice’s simultaneous vulnerability and strength, often in the same scene, and our terror mounts in direct proportion to how much we relate to her. It’s an incredible performance that doesn’t get enough praise, and her character is the one that lingers, notwithstanding quotable Hannibal Lector lines. The patriarchy is out in full force throughout this film, and Clarice is the understated warrior pushing back — in part to save the woman who’s been taken captive, but also to save her own sanity and sense of self.

12) Emmi (Ali: Fear Eats The Soul)

Fassbinder’s post-German Economic Miracle melodramas are not to everyone’s taste, but Ali: Fear Eats The Soul might be the exception. A carefully drawn, achingly beautiful love story about an older white woman and an immigrant Moroccan laborer who fall for each other, against all odds and objections, it has the kind of appeal that wears down modern sensibilities skeptical of earnestness. As Emmi, Brigitte Mira conveys her loneliness and need for connection so effortlessly that you can’t help but want the best for her, and there’s joy in her unlikely connection to El Hedi ben Salem’s Ali that you can’t help but celebrate. Alas. Things being what they are, the differences in age and race don’t go down well with either of their circles, and we’re headed for a precipitous fall. There are many scenes in Fassbinder’s masterpiece (one of them, anyways) that stand out; I think of Emmi’s face in the shitty bar, pressed against his shoulder as they dance to the jukebox. If there’s a better single image of what it is to be cast out by cruel society and wanting basic human comfort and companionship, I don’t know what it is. That ben Salem would commit suicide not much later is the kind of extra-textual note some critics despise, but it adds an almost unbearable sadness to an already very sad film.

13) Ethan Edwards (The Searchers)

John Ford and John Wayne had made 11 films together, and cemented the iconic “John Wayne-type” in westerns, before 1956’s The Searchers, in which they seem intent on burning their mythos to the ground. Wayne’s Ethan Edwards is not the stoic, wry gunslinger compelled by circumstance to take care of business whether he wants to or not, a reluctant hero with a rough exterior sheltering a wounded soul, a man’s man in an unforgiving land. No, Ethan Edwards is a racist piece of shit, the kind of guy who casually shoots out the eyes of Comanche corpses on principle, because he knows the desecration of their bodies complicates their journey into the afterlife. He’s also the kind of guy who rejects his own kin due to their 1/8 Comanche blood, and who is willing to commit all kinds of violence and suffer all kinds of depredation to rescue Natalie Wood from the natives, whether or not she wants rescuing. He’s fixated on purity — racial and gendered — and his quiet mania leaves bare to the ugliness at the heart of the genre. It’s such a bold characterization that we’re still trying to figure out what was going on here. And why, when he runs into his brother’s burning house, does he cry out for his brother’s wife? Edwards is an enigma with unsettling depths and secrets, with hate at his core, and he changed the western forever.

14) Jackie Brown (Jackie Brown)

Pam Grier is a badass. On this, we all can agree, I’d hope. Her sequence of Blaxploitation films — some of them quite bad — were always recuperated by her performances and formidable screen presence. In Quentin Tarantino’s love letter to her, by way of adapting an Elmore Leonard novel, she towers above everyone else, and the camera loves her. She’s sweet, calculating, and more than able to hold her own, and she helped Tarantino make his best film. The halting, anxious desire between her and bailbondsman Robert Forster is a thing of beauty, but in the end, this is Grier’s film. Jackie Brown is the title of Jackie Brown for a reason. The opening sequence alone — as she walks through the airport in a single tracking shot — would’ve made this true. The plot twists and her foresight, getting the best of everyone around her and looking fabulous while doing it, cement it.

15) Jesse and Celine (Before Sunrise, Before Sunset, Before Midnight)

They meet-cute on a train in Europe and talk through the night. They’re reconnected years later and pick up where they left off. When we join them again, they are all grown up and grappling with the pressures of adulthood, and the accumulation of all the slight injustices and resentments a lifetime can bring. Richard Linklater’s Before Trilogy is not just an early practice attempt at the time-lapse of his later Boyhood; it’s a masterpiece in its own right. The characters of Jesse and Celine are so specific, so filled with endearing and maddening attributes, and so painfully familiar that they don’t have to do much but engage in the films’ discursive dialog to pull you into their sphere. The almost-kiss in the sound booth, the nearly one-take gondola ride, the closing moment of agreed-upon fiction between them (clearly echoing Satyajit Ray’s The World of Apu) … these and so many other moments add up to something heartbreaking and wonderful. And it’s all borne out of the characters themselves, the way they relate and come to know each other, call each other on their bullshit, love each other despite it. Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy, together with Linklater, crafted characters for the ages here. They are too real to ever feel dated.

16) MacGruber (MacGruber)

Audiences flatly rejected MacGruber, an unlikely feature-length spin-off from a throwaway SNL sketch. This is due to several things — caustic Lonely Island humor, a go-for-broke dedication to the awkward scenario, extreme violence in a comedy — but mainly I think it’s MacGruber’s character himself. Every single detail about him is played for maximum discomfort — his catchphrase, aimed at nemesis Dieter von Cunth (Val Kilmer), is “Let’s go pound some Cunth,” which probably in and of itself would’ve killed any box office aspirations. (Sidekick Ryan Philippe almost steals the show with this exchange: “Do you have to say that?” “What, it’s my catchphrase! It’s witty!” “Is it?”) But the total commitment to not giving a fuck carries the day. As MacGruber, Will Forte delivers his most indelible performance, and any allegations of stupidity and bad taste just get kind of written off. Witness his explanation of how he and Cunth came to be enemies and tell me it’s not horrifyingly funny.Or the montage where he gets the old team back together — who happen to be, to a member, professional wrestlers. Classic MacGruber.

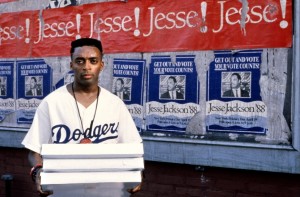

17) Mookie (Do The Right Thing)

Since its release, debate has raged whether Spike Lee’s Mookie did, in fact, do the right thing. Lee, of course, was smart enough not to show his hand, and that’s what lends so much power to the character. Mookie is caught between worlds that don’t particularly seem like they’re going to coalesce, and his final explosive decision is his first real act of agency in the film. How could it be otherwise? But he’s a fully realized character (Lee’s best) and audience stand-in, sort of a Virgil guiding us through a sweltering day in hell. His scenes with Rosie Perez are wonderfully intimate, his relationships with the other characters believably conflicted, and imbued with a detachment that can’t last. It all works — he grounds the film in his gestures and expressions, and it closes with the repercussions of an act no one saw coming. People still can’t agree what it means, but it means something.

18) Samantha (Her)

In the run-up to Her, there was a lot of hand-wringing about the notion of a guy (Joaquin Phoenix) falling in love with his operating system, which has the voice of a woman and an AI component that make her something of a made-to-order surrogate for his desire. In a marketplace where women get few good roles and most romances center on the men, that’s an admittedly icky proposal. However, Phoenix, director Spike Jones, and especially Scarlett Johanson as Samantha subvert those expectations in incredible form. Not only is Samantha the most fleshed-out character in the film, she’s as real as a character can be in fiction … which is sort of the point. Without a face to convey expressions or a physical form at all (a particularly ironic note, given Johanson’s relentlessly sexualized image), Samantha becomes instantly knowable and poignant. This is a film where the central character, whose growth drives it, never appears on screen. Those early protests came too soon; there’s a lot more going on here than the sublimation of female experience in favor of the male protagonist. In fact, the opposite is true. Samantha stands out through her physical absence, and yet is as real as any other character on film.

19) Willy Wonka (Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory)

For all the faults of his current fetish for dandyish costuming, outlandish accents, and forced whimsy — and they are many — late-period Johnny Depp did do everyone a favor when he and Tim Burton remade Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The two of them threw into stark relief the brilliance of Gene Wilder’s performance in the original. By turns comic, exasperated, soulful, melancholy, and outright terrifying, Wilder’s Willy Wonka is a singular achievement (and now an instantly meme-able fixture). The same guy who sings “A World of Pure Imagination” also arranges for the gruesome dispatching of children (not to mention the Boatride Through A Tunnel In Hell, which haunted my nightmares for years) — and the climactic scene when he dismisses Charlie continues to sting. Movies generally intended for kids don’t usually skew so dark, but Roald Dahl’s material was never quite cuddly, exactly. And Willy Wonka — puckish, filled with one-liners and witty asides, and offhand malevolence — embodies everything magical about this film, which will continue to both amuse and keep 9 year olds up at night for many years to come.

20) The Wicked Witch of the West (The Wizard of Oz)

The green face, the cackle, the flying monkeys. The Wicked Witch of the West occupies a role of very specific villainy for generations of film-goers. Like Dorothy’s dream, she exists in an alternate dimension, where it seems like anything could happen that she wills. In all the discussions of The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy’s quest for “home” and what that might mean, the escapism embodied by Technicolor and the mundane black and white, dust-swept Kansas, the ways in which the familiar is made uncanny, The Wicked Witch stands out. She’s an archetype but also unique in her details, and still manages to intimidate. The scene in which Auntie Em’s face in the crystal ball morphs into hers is one of the great moments of cinema — as children, what could be scarier than the idea that those you most trust could also harbor villains of epic proportions? Of course, leaving all the formal analysis aside, she’s just scary as hell.