Back in January of this year, inspired by the folks at WIF and the initiative they created, I resolved to watch 52 films by women directors in 2017. With only a few days left on the calendar, it seems like a good time to check back in on this “challenge.”

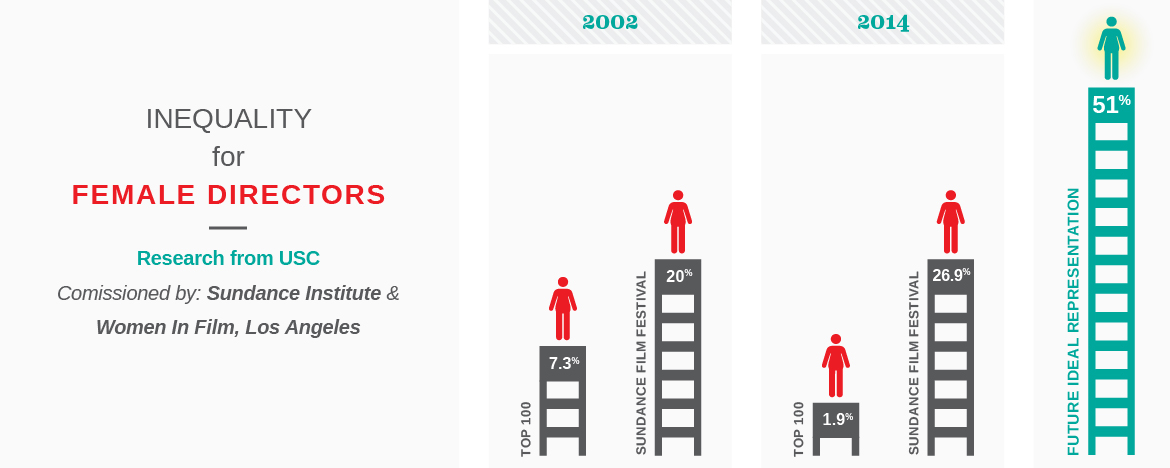

“Challenge” definitely belongs in quotation marks here. While it’s absolutely true that our culture defaults to the masculine in basically all realms, and women directors are grossly underrepresented, it turns out that it’s really not that difficult to hit this mark — embarrassingly easy, in fact, with even minimal effort. The problem, of course, is that many of us just don’t make the effort. One thing I learned this time around: when presented with two viewing options of more or less equal interest, just watch the one that isn’t by the dude. It’s not revolutionary, but it’s also not exactly a back-breaking, Herculean effort, and you’ll often be rewarded with amazing films you might’ve missed thanks to cultural inertia (and patriarchy!).

“Challenge” definitely belongs in quotation marks here. While it’s absolutely true that our culture defaults to the masculine in basically all realms, and women directors are grossly underrepresented, it turns out that it’s really not that difficult to hit this mark — embarrassingly easy, in fact, with even minimal effort. The problem, of course, is that many of us just don’t make the effort. One thing I learned this time around: when presented with two viewing options of more or less equal interest, just watch the one that isn’t by the dude. It’s not revolutionary, but it’s also not exactly a back-breaking, Herculean effort, and you’ll often be rewarded with amazing films you might’ve missed thanks to cultural inertia (and patriarchy!).

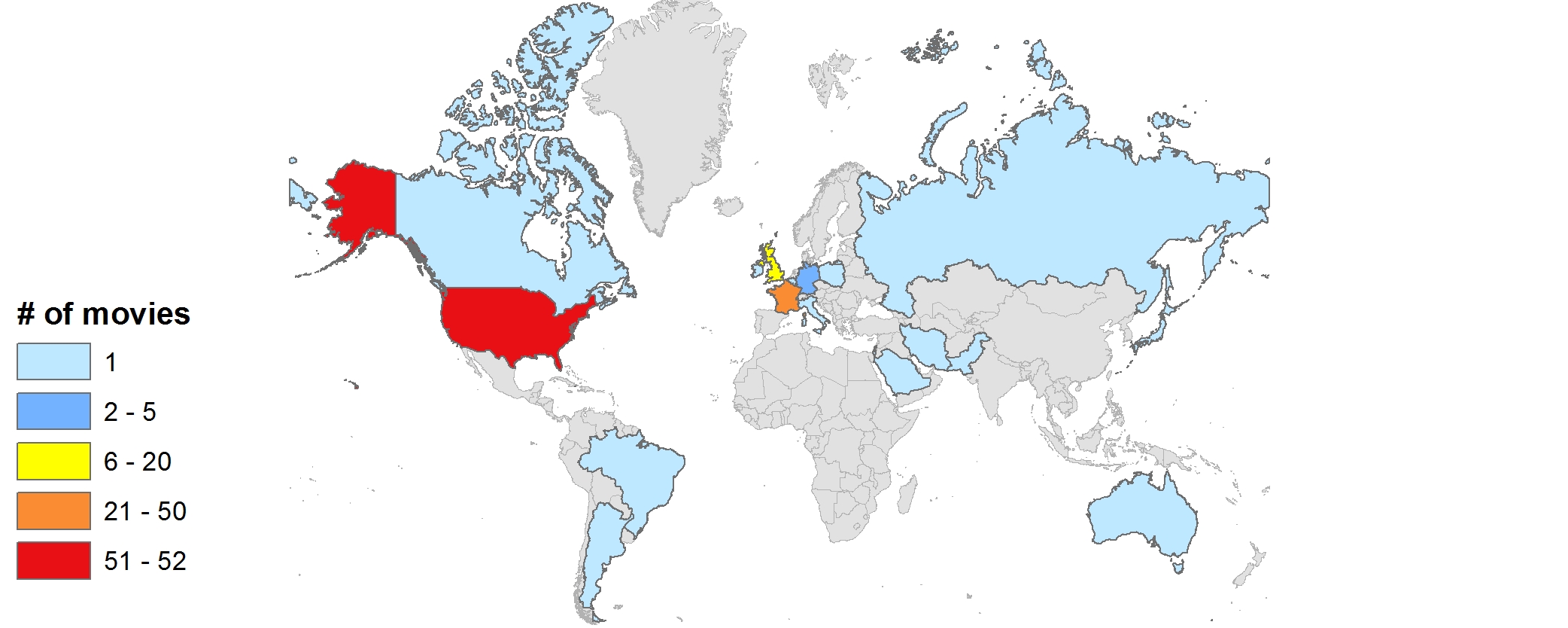

Some numbers from my navel-gazing data self-analysis. I watched a total of 66 features and 36 shorts by women, mostly first-time viewings. This is roughly 30% of everything I watched, give or take. (Film only; none of this includes serialized TV, a realm in which women directors have been faring better.) Women directors from 18 countries were represented; 10 from outside the U.S./Canada/England/Western Europe.

first-time viewings. This is roughly 30% of everything I watched, give or take. (Film only; none of this includes serialized TV, a realm in which women directors have been faring better.) Women directors from 18 countries were represented; 10 from outside the U.S./Canada/England/Western Europe.

Every decade since cinema’s inception made an appearance … except for the 1980s, weirdly. Another, even longer piece would address the prevalence of women behind the camera in early film (and yet another would include discussions of women’s leading roles as editors and other non-directing contributions). The overwhelming majority were U.S. productions since 2010.

What conclusions can be drawn from any of that? Not too many. There was no rigor to this survey: it’s simply a reflection of the kinds of films, genres, and periods that interest me personally, and as they intersect with current availability and, presumably, the historical/material conditions of production and women’s participation in the director’s chair. (Though the self-selection largely precludes drawing deeper insights; I’m pretty sure women were directing films in the 80s.) Those intersections are fascinating, though, and worthy of more serious consideration. Maybe next year.

In any case, I saw a lot of great stuff, and wrote about much of it. Bolded titles in the list below link to earlier write-ups — the list itself has a bit of a virtue-signalling flavor, I’m afraid, but I’m including it both for those links and for anyone interested or looking for something to watch tonight. (Watch The Lure so we can talk about it!)

And here are 10 films by women that I didn’t write about, for lack of time or occasion. This is not a “10 Best By Women Directors” list — I am certain no one needs a straight white U.S.-based film dude constructing that sort of thing — and doesn’t reflect any particular cross-section. These are just a handful of films that made an impression on me in 2017 but didn’t show up anywhere on the site until now.

I was so enthusiastic about this whole process, initiated with some amount of intentionality but eventually kind of humming along in the background, that it’ll be an annual pledge for me. See you in 2018.

I missed Desiree Akhavan‘s feature debut when it came out in 2014, amid what seemed at the time (to me) a glut of  millenial cringe-comic examinations of Relationships In The Big City (Of New York). I’m glad I caught it now, because it’s actually an accomplished, frank affair.

millenial cringe-comic examinations of Relationships In The Big City (Of New York). I’m glad I caught it now, because it’s actually an accomplished, frank affair.

Representations of bisexuality are rare enough, much less ones so attuned to cultural identities and desires. It’s smart filmmaking, too, with an admirable frankness about sex that might owe something to Girls (on which Akhavan would appear for several episodes the following year) but plays here with a rhythm and set of interests all its own.

2. Le Bonheur

Agnès Varda is all over the Best Documentary lists this year for Faces Places, but I only just caught up with her 1965 masterpiece.

Amy Taubin, for Criterion, sums up its enduring mystery well: “Is it a pastoral? A social satire? A slap-down of de Gaulle–style family values? A lyrical evocation of open marriage? Is the central character a good husband who knows how to enjoy life, a psychopath, a cad, or an unreal cardboard construction? Are the implications of the film’s title ironic or sincere? And, indeed, what is happiness?”

The story is remarkable in its banality, impossible and uncanny cheeriness, and the wash of saturated colors that construct a sort of hyper-reality. Le Bonheur is the kind of film that seems to only result in questions like Taubin’s, or mine — “What the hell did we just see?” Varda is among the greats of this or any age.

One of the pivotal films of the L.A. Rebellion, Julie Dash‘s sweeping, evocative, dialect-heavy portrait of Gullah women at a cultural and historical cross-roads is a wonder. There’s really nothing else like it: the poeticism comes through in the language and the images, with tradition echoing into the unsure present and the conflicted future of a people. It’s gorgeous in every way.

cultural and historical cross-roads is a wonder. There’s really nothing else like it: the poeticism comes through in the language and the images, with tradition echoing into the unsure present and the conflicted future of a people. It’s gorgeous in every way.

The film will make another, more detailed appearance (eventually) in the Counter-Programming series, and it remains a profound injustice that Dash isn’t better known, but Daughters of the Dust deserves as many mentions as it can get. (For those who are already admirers, Scout Tafoya’s video essay on the film is a must.)

4. Fish Tank

My arguably overheated enthusiasm for Andrea Arnold’s American Honey is already a matter of public record, so it’s probably no surprise that I returned to her work again and again in 2017.

Wasp, Red Road, and Wuthering Heights all appear on the list below, but it’s Fish Tank that left the biggest bruise. Katie Jarvis‘ lead performance, as another of Arnold’s lower-class heroes coming of age through confusion and self-sabotage, is blistering, and the director’s eye for casually realist detail is in full effect. At a crucial moment in its third act, you might find yourself hoping against hope that things aren’t headed where they seem to be; Fish Tank‘s magic comes the moment after, when you realize that of course they are. Arnold is without judgment and the film never devolves into poverty-porn. It’s honest and bracing.

5. Forever’s Gonna Start Tonight

Eliza Hittman is another filmmaker having a big 2017, with her sophomore feature Beach Rats showing up on more than a  few cinephile lists.

few cinephile lists.

I didn’t have a chance to catch that one, but her 2011 short guarantees I will eventually. Filmed on location in a Brooklyn immigrant community and the adjacent dance clubs our protagonist flees to at night, Hittman’s film conveys a palpable sense of place and of being stuck in between– nostalgia, modernity, adolescence, adulthood. It packs a lot of growth into its 16 minutes.

6. Frank Film

It’s hard to imagine a purely experimental short work winning an Oscar these days, but things were apparently a little different in 1974, when Caroline and Frank Mouris’ exuberantly postmodern Frank Film arrived.

It’s pure auteurist pastiche. The Mourises “researched, cut out, and glued onto acetate cells 11,592 images – photographs, illustrations, and other graphic work – arranging them in geometric patterns that cascade up, down, and across the frame, timed to both an internal rhyme scheme (pie begets desserts, televisions beget other appliances) and to the soundtrack.” The effect is bewildering and trance-inducing, something like Len Lye by way of Jasper Johns, with John Cage throwing the I-Ching on the repetitive, overlapping score. Honest-to-god mindfuckery, and I mean that in the best way possible.

7. Landline

Gillian Robespierre and Jenny Slate followed up their unfailingly sweet abortion rom-com Obvious Child with this 90s  throwback about family dysfunction and sisterhood. If Landline lacks the sure narrative footing (and irresistible logline) of the previous film, it makes up for it in shaggy charm and small moments of recognition. (The lovingly detailed, decade-specific touches don’t hurt either, at least for those of us who very much remember dial-up internet.)

throwback about family dysfunction and sisterhood. If Landline lacks the sure narrative footing (and irresistible logline) of the previous film, it makes up for it in shaggy charm and small moments of recognition. (The lovingly detailed, decade-specific touches don’t hurt either, at least for those of us who very much remember dial-up internet.)

Slate is wonderful, again, but it’s much less of a one-woman show here, with Edie Falco, John Turturro, Jay Duplass, and (especially) Abby Quinn as her wise-ass little sister rounding out the ensemble.

Her 2017 Mudbound was stately, ambitious, and filled with good performances, but the smaller scale urgency of Dee Rees‘ 2011 film is much more to my taste.

Her 2017 Mudbound was stately, ambitious, and filled with good performances, but the smaller scale urgency of Dee Rees‘ 2011 film is much more to my taste.

As the protagonist Alike, a queer teen navigating treacherous water, Adepero Oduye turns scene after scene into moments of quiet revelation and halting discovery, conveying fierceness and vulnerability the whole time. It’s a remarkable performance in a film that feels genuinely dangerous, and Rees structures the narrative with total confidence.

9. The Beguiled

Few directors, women or otherwise, capture insularity like Sofia Coppola, and The Beguiled is Coppola at her most closed-off. There’s something  undoubtedly perverse about a Civil War story in which the Civil War barely registers, much less slavery, and many viewers were critical of it for this reason.

undoubtedly perverse about a Civil War story in which the Civil War barely registers, much less slavery, and many viewers were critical of it for this reason.

That’s fair, but it’s also of a piece with the film’s Gothic aspect of creeping dread, much more haunted house narrative than historical drama, its costuming and setting aside. The pervasive eeriness is (almost) all atmospheric, with Coppola drawing out sexual tension and jealousy in this weird cloister. When things finally, definitively go off the rails, it almost comes as a relief.

10. We Need To Talk About Kevin

I watched Lynne Ramsay‘s tour-de-force adaptation on a plane on the way to a funeral, which may or may not have been the best way to see it.

I watched Lynne Ramsay‘s tour-de-force adaptation on a plane on the way to a funeral, which may or may not have been the best way to see it.

Ramsay’s assured pacing and cross-cut narrative is the epitome of slow-burn psychological terror, with a never-better Tilda Swinton grounding the whole thing in utter, discomfiting believability. The unease that registers across her face throughout is a hard aspect to shake once it’s through — an unease with motherhood in the first place morphing into dawning awareness, outrage, and remorse. There is ample room for exploitation in the story of a disturbed child, but We Need To Talk About Kevin finds personal tragedy in the haunted social body instead.