In the original text of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, first published privately in Italy in 1928, the word fuck appears 26 times.

He first comes on the scene as one of the upper-class Lord Chatterley’s friends entertains the company by explaining, while denouncing sexual prudery and praising free love (with restraint), that he doesn’t “over-eat [himself] or over-fuck [himself]”; he makes his curtain call in the final moments, when the titular lover tells his now-divorced, disgraced beau that they “fucked a flame into being.” (“Even the flowers are fucked into being,” he goes on, “between the sun and the earth,” at the very least displaying a poor knowledge of seed germination.)

In the 2015 BBC film adaptation of the novel, our featured star makes no appearances. (We are forced to wait until minute 86 to even get a “cock”.) But just as peculiarly, there are no upper-class friends praising free love and denouncing sexual prudery, and the film ends not with an ambiguous letter between ambiguously placed protagonists but with them driving off snuggled in the front seat of a period-appropriate car.

To be fair, no adaptation of Lady Chatterley (that I have seen) has managed to include the more risqué language from the original text. None have included the preposterously hippie-ish scene, a scene desperate to be snuck into W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism, of the two protagonists intertwining flowers in each other’s public hair as a pseudo-marriage. (His dick, they decide, is named John Thomas, and her vagina is named Lady Jane. If, in the future, you wish to refer to your genitals while making a literary reference, you are welcome.)

But why is it that adaptations, fresh from excising anything more risqué than two characters being horizontal simultaneously, also insist on making mincemeat of the original structure? The question soon becomes: why adapt Lady Chatterley at all? The fundamental narrative—a woman who has married into an upper-class family has an affair with a servant at the house—could come from a hundred and ten sources.

The answer cannot be the vibrancy and brilliance of the original work. Make no mistake: by Lawrence’s standards, by the standards of the man who created Women in Love, The Rainbow, and Sons and Lovers, Lady Chatterley is a bad novel. It is such a bad novel that F.R. Leavis, his earliest proponent and his defender against T.S. Eliot’s constant barbs (yes, all British writers were required by law to go by initials until WWII), directed readers to read Lawrence’s defense of the novel instead. It wanders aimlessly and confusedly through its tragedy and ends on a famously bizarre note: almost all of the drama promised by the premise happens while Lady Chatterley is in another country, receiving updates by letter.

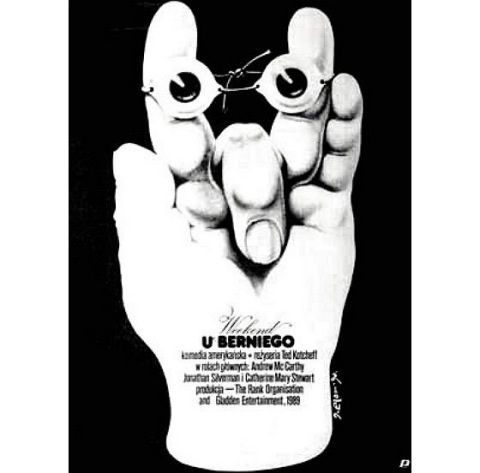

And one gets the feeling looking at polite adaptations like this film that while the explicit goal may be something to the effect of making it more alive for the current viewer and bringing our cultural heritage to the modern age, that the real reason these books are dragged back to life, Weekend at Bernie’s style, is more than anything because of an embarrassment about their knotty inscrutable structure.

The adapters serve as a mixture of studio-notes-givers and high school composition teachers, guiding Lawrence away from his mistakes and towards a proper narrative. “It’s a wonderful first draft, Lawrence, but why not have Mellors, the lover, be a World War I veteran who served in Lord Chatterley’s unit? We could even have him be present when he is crippled, to really wrap everything up emotionally,” the studio notes would read. “It’s a wonderful, passionate first draft,” the composition teacher writes, “but the themes are a bit all over the place. Why don’t you compress the class dynamic and make it clearer, and situate the story more in its setting and time?”

It is this condescension that suffuses not just this adaptation, but all the adaptations of British classic novels that jump from art house theater to PBS to high school classrooms with exhausting speed. What ultimately defines them is not their aesthetic boredom, their interchangeable soundtracks, their unchanging stable of passionate young hunks and energetic, quirky young women who can look fashionable in styles from the Georgian era clear through the Edwardian.

What defines them, above all, is their condescension for their source material. The texts themselves are treated with the same barely hidden contempt with which the crippled Lord Chatterley is treated. “Don’t mind this forty-page digression on industrialization,” the smiles seem to say; “Lawrence didn’t really know what he was doing. For decorum’s sake, we’ll pretend it never happened.”

One wishes and hopes for an adaptation by someone with a little less decorum, someone who could—to quote from a novel—“fuck a flame into being.”