For most revered mid-century filmmakers, noting that a particular film featured their first original screenplay and was their first in color would seem to guarantee it additional attention. Curiously, that’s not really the case for Satyajit Ray‘s Kanchenjungha (1962). A careful tapestry of small interactions set against a backdrop of physical grandeur and social change, it seems to get lost in the critical shuffle, functioning as a kind of way station between the narrative sweep of the first two entries in the Apu trilogy and the more refined, self-aware craftsmanship of The Big City and beyond.

That’s unfortunate, because it’s a wonderful movie, but it was there from the start in Kanchenjungha‘s reception — this sense of something ephemeral or slight. Bosley Crowther, for instance, rather impatiently reviewed Kanchenjungha for the Times in 1966 (it took 4 years after its release to premiere in the U.S., further evidence of its curious also-ran status). Approaching Ray with impatience is, of course, a pretty bad idea in general, as Crowther’s assessment demonstrates:

Lest one be misled by the title of Mr. Ray’s unfamiliar film into thinking it may have something to do with mountain climbing on the world’s third highest peak, be assured that there is nothing as dramatic or strenuous as mountain climbing in it. Indeed, the great mass of Kanchenjungha is revealed only at the end, when the mists roll away and we are shown it as an evident symbol of the emergence of Indian society—or social snobbery—out of the mists of the past.

Armed with a backhanded compliment and dreaming of another epic of Bengali impoverishment (or possibly, inscrutably awaiting the arrival, 26 years later, of Cliffhanger), Crowther concluded that Ray had “not bitten off as much as he could chew.” Watching it for the first time this year, I was instead struck by how much Ray managed to cram into the text, and how forward-looking Kanchenjungha is, what a break it represents.

Where the “one-man New Wave” of the Apu bildungsroman focuses on the struggling and striving rural poor, with the kind of formal “naivety” that only someone actually making it up as they go along can manage, and The Big City on the social tensions of a more urban modernity, Kanchenjungha falls somewhere in between. The film’s narrative concerns an upper-class family on holiday in Darjeeling, in the shadow of the titular mountain … or what would be its shadow, if the rains would ever lift. Ray creates an almost-familiar nouvelle vague dynamic; his characters seem suspended, held together by place and circumstance for the duration, playing out small, interrelated, naturalistic dramas between them in the open air. Kanchenjungha‘s basic tension comes from this: it’s at once intimate and expansive, grounded in isolated family discourse that clearly hints at tumultuous worlds beyond the fog.

Where the “one-man New Wave” of the Apu bildungsroman focuses on the struggling and striving rural poor, with the kind of formal “naivety” that only someone actually making it up as they go along can manage, and The Big City on the social tensions of a more urban modernity, Kanchenjungha falls somewhere in between. The film’s narrative concerns an upper-class family on holiday in Darjeeling, in the shadow of the titular mountain … or what would be its shadow, if the rains would ever lift. Ray creates an almost-familiar nouvelle vague dynamic; his characters seem suspended, held together by place and circumstance for the duration, playing out small, interrelated, naturalistic dramas between them in the open air. Kanchenjungha‘s basic tension comes from this: it’s at once intimate and expansive, grounded in isolated family discourse that clearly hints at tumultuous worlds beyond the fog.

“The idea,” Ray told Andrew Robinson, “was to have the film starting with sunlight. Then clouds coming, then mist rising, and then mist disappearing, the cloud disappearing, and then the sun shining on the snow-peaks. There is an independent progression to Nature itself, and the story reflects this.”

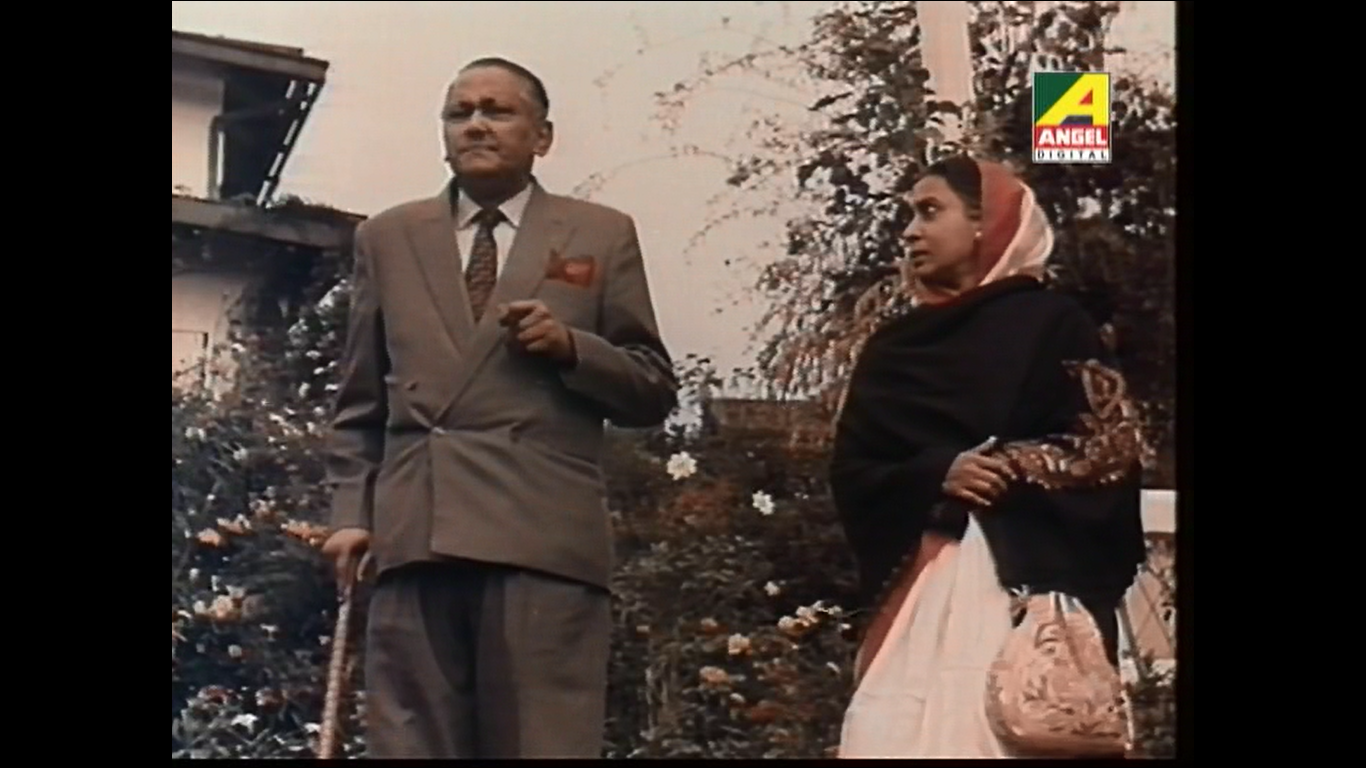

That story concerns the stridently pro-British patriarch Indranath (Chhabi Biswas, so memorable as a very different sort of figure in 1958’s The Music Room); his cowed wife Labanya (Karuna Bannerjee), subservient but possessing hidden reserves of agency; their eldest daughter Anima (Anubha Gupta), unhappily married to Shankar (Subrata Sensharma); dissolute playboy son Anil (Anil Chatterjee); and the youngest daughter Monisha (Alakananda Ray), who they hope will find a man on this mountain excursion.

Monisha is the moral center of the narrative and the audience surrogate. Pressed to converse, and hopefully pair up, with Mr. Bannerjee (N. Viswanathan) — the Anglicized favorite of her Anglophile industrialist of a father — her attentions turn instead to Ashok (Arun Mukherjee), a young, barely employed figure of the new generation. Poetic, passionate, working class, unapologetic in his anti-colonial patriotism, contemptuous of the idle wealthy, and linked with the natural world, Ashok is everything Bannerjee (and her father) is not. When Indranath offers Ashok a job when they all return to Calcutta, Ashok declines, a moment of small revolution. A reckoning is coming for all of India, a generational struggle boiled down to multiple sets of two.

That reckoning won’t happen within the structure of Kanchenjungha. The holiday ends without a marriage (or, for that matter, a divorce). Ray is content to set up the dominoes, and far less interested in knocking them over. The film’s ending is open to any number of possibilities, though, contra Crowther, the long-delayed appearance of the mountain itself isn’t just symbolic of “the emergence of Indian society” (whatever that means). It seems instead part of a continuum, a brute, beautiful fact reasserting itself but transformed; its textual meaning is more a function of the fact that Indranath fails to even notice its emergence … this event that the whole film, the whole holiday in the film, has waited for. He’s lost in thought instead.

That reckoning won’t happen within the structure of Kanchenjungha. The holiday ends without a marriage (or, for that matter, a divorce). Ray is content to set up the dominoes, and far less interested in knocking them over. The film’s ending is open to any number of possibilities, though, contra Crowther, the long-delayed appearance of the mountain itself isn’t just symbolic of “the emergence of Indian society” (whatever that means). It seems instead part of a continuum, a brute, beautiful fact reasserting itself but transformed; its textual meaning is more a function of the fact that Indranath fails to even notice its emergence … this event that the whole film, the whole holiday in the film, has waited for. He’s lost in thought instead.

Unlike his contemporary (and earlier entrant in this series) Ritwik Ghatak — for whom Partition is a metaphysical presence, a ghostly “hunk of iron and steel,” or an entirely physical one, like a train bisecting the countryside — Ray constructs the entire mise-en-scene in Katchenjungha as a post-colonial contradiction. The mountain itself can’t be said to denote Partition any more than it stands in for a generational divide. It looms, mostly unseen, over the characters strolling contemplatively, stopping, arguing, dismissing, apologizing, reconnecting; there’s something almost Linklater-like in the desperate conversation, an eddying stillness. The relations between them, physical and emotional, and their movements give shape to the larger themes of the film, as Ruma Chakravarti notes:

The film unrolls in the form of several conversations between pairs of characters as they take long rambling walks. At no point in the film are these characters more than a few minutes apart from each other. I felt the different stretches of mountain roads were almost an allegory for the different paths people take. The married couples have their conversations in situations where they are generally static. The younger un-married characters such as Monisha, Mr Banerjee and Ashok are shown walking almost constantly.

If the Apu trilogy charted Ray’s engagement with the Bengali underclass, The Music Room with a patriarch’s fading glory, and The Big City with a tumultuous modernity, Kanchenjungha is located at a crucial mid-point, where any number of paths are open and history is actively being contested. It’s an essential masterpiece from a career that seems to have produced only masterpieces.