Shirō Toyoda’s The Mistress is based on Mori Ogai’s Romantic novel Wild Geese (and sometimes referred to by the title of the original, as Criterion does). The film is in some ways a familiar melodramatic narrative about the crushing of a woman’s desire under patriarchy — a treatment dismissively summarized in 1959 by Bosley Crowther of The New York Times as “a morally mawkish situation upon a tear-misted screen.” But this (ironically patriarchal) scorn misses so much of the film’s nuance and historical context, not to mention the beauty of its images.

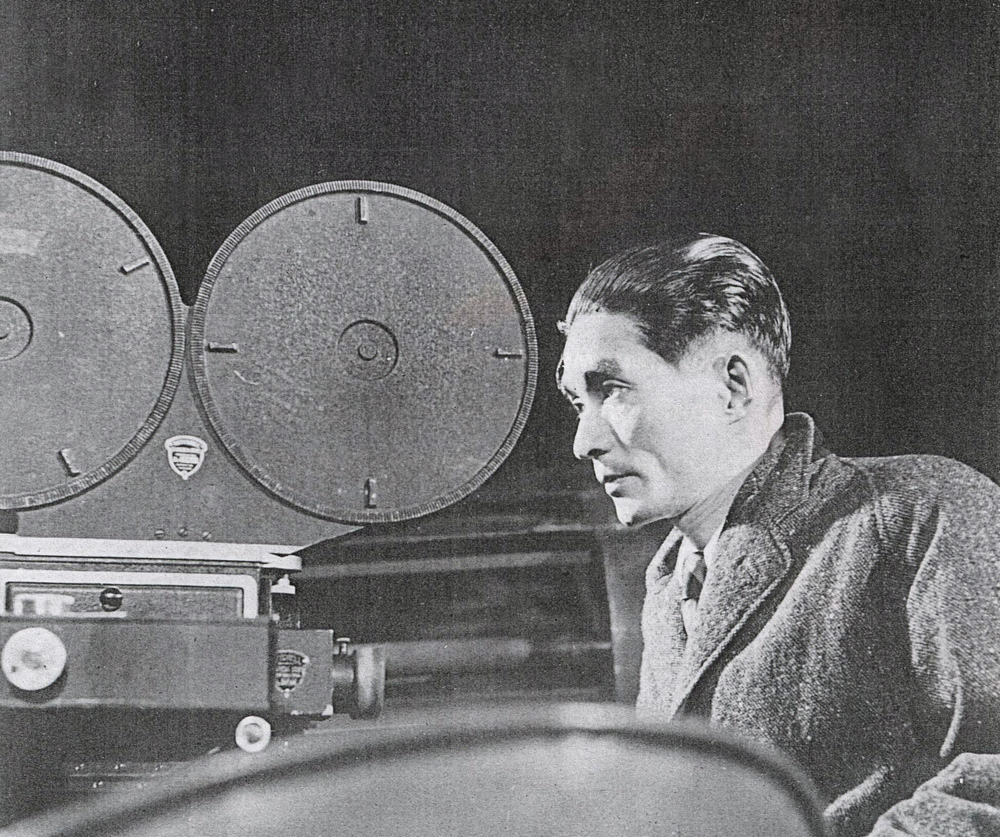

In his early days, Toyoda apprenticed under Yasujirō Shimazu, whose Our Neighbor, Miss Yae was discussed earlier in this series. The two share similar social concerns and a focus on a changing society, not to mention a fluidity with camera movement that distinguishes their approach from the more celebrated works of artists like Ozu.

The narrative of The Mistress / Wild Geese is simple enough on its face. Our protagonist Otama (the great Takemine Hideko) was once tricked into a false marriage, and is now deemed “damaged goods” (a term her scheming neighbor feels comfortable deploying to her face).

With an ailing father and few other options, she agrees to become the mistress of Suezo, a man she believes to be a widower who runs a kimono shop.

In fact, she is tricked once again: his wife’s not dead at all, and he’s a despised moneylender. In the mean time, she falls in love with a local college student, Okada, who passes by her new house every day, but circumstances conspire to keep her trapped, like the caged bird on her windowsill. Okada will be leaving to pursue a medical career in the West, her father (initially far more sympathetic) has grown accustomed to living in less brutal poverty than before, and Suezo vows never to let her go.

It’s not hard to see how Crowther and others might simply read this as a “weepie” and blithely move on. But, even ignoring the fact that “weepies” have long been dismissed by male critics for entirely insulting reasons, the subtexts both Ogai and Toyoda sneak into the tale make it far richer.

The Mistress / Wild Geese is also the story of a conflict between rationalism and individual desire, head and heart, with special attention to a woman’s place in a changing Japan. Set in the late-19th century but screened for audiences after the Second World War, there’s a palpable sense of outrage and sorrow for the traditional “caged bird” of such melodramas. As the story progresses, Okada begins to consider breaking free from the shackles imposed upon her, but this desire butts up against the contradictory realities of her situation.

In Toyoda’s film, the heroine, Otama, is no longer resigned to suffer in silence. Like her contemporaries, she raises her voice in rebellion against the one who has caged her. This Romantic ideology of victim consciousness resonated strongly· with the audience of postwar Japan. This criticism of authority is also found in the popular 1947 novel, The Setting Sun, by Osamu Dazai, when the character Kazuko speaks of a time when adults taught their children that revolution and love were evil. After the war, however, distrust of the former beliefs developed and Kazuko “came to believe that revolution and love in fact are the best and most delicious things in this life … Humans were born for love and revolution.”

This sensibility is contrasted with the feudal-borne sense of duty and propriety voiced constantly by the other characters, especially their repeated refrain to “be reasonable,” to recognize the limitations of desire and love-matches and provide for the community (in this case, embodied as literal patriarchy by Otama’s father). These rationalist societal codes aren’t so much contrasted with the anti-communal, capitalist impulses embodied by the moneylender as they are integrated with them. This is a society rife with contradiction, but only resulting in further female subservience, now to capital and the dominant norms of the community.

Rationalism takes other forms, too. Her college-student love is studying to be a doctor, that ultimate rationalist profession, and hoping to pursue a career opportunity in Germany, that ultimate rationalist nation. He may love Otama, but there’s no place for that here, and he has things to accomplish. (How single-minded is he? Irvin notes that in the book, Okada’s evening walks are so rigorously routine that neighbors use them as markers of time, a sly reference to a famous legend about the regularity of Immanuel Kant’s afternoon constitutional in Königsberg.)

Meanwhile, Toyoda time and again frames his heroine through the slats of her new home, evoking a symbolic prison. Suezo’s gift of a caged bird with which to “amuse” herself doubles down on this symbology (as does the heroic Okada’s killing of a snake who threatens the bird; the snake is dispatched, the whole in the cage filled, the bird once again without recourse to the sky).

The Mistress / Wild Geese exhibits all of this without laying it on as thick as it might sound; we spend far more time studying the shifting looks on faces and the spaces between foreground and back, emphasizing power relations and internal psychologies. And, though the film focuses most acutely on the relations between mistress, scorned wife, maid, and the assorted neighbors Suezo profits from as a usurer, there’s enough unease to go around.

Okada’s friend, a liberal arts student who knows he’s in love with Otama before he does, puts it plainly, implicating the entire society with a shrug:

You’re a brilliant student in medical school, and she’s an uneducated, kept woman. In today’s Japan, you two can’t be involved romantically. Just like her, neither you not I are free from the restrictions of this Meiji era. But for all that, will you conform to those restrictions or break out of them?

That is: head or heart? There is little doubt which one the men of this film will choose. Otama may be a different story. As we watch her watch the wild geese of the title ascend in the film’s closing frames, her face is impassive, revealing nothing. Perhaps she’s resigned to this fate. Perhaps she’s looking to a new day and a less rigid social order. Perhaps she’s making a plan.

Toyoda keeps it in tight close-up. We’re left only to wonder.