Sunrise is an undisputed masterpiece of the silent era’s final days, a staggering set of technical achievements in service to melodramatic fairy-tale pathos. It’s also the story of how sometimes the only thing needed to put the spark back in an empty marriage is a little bit of attempted murder.

F.W. Murnau was brought to Hollywood from Germany by William Fox and given carte blanche to make his film. Fox had been so impressed by 1924’s The Last Laugh, its sweeping long-takes and Expressionist superimpositions so different from the Hollywood productions at the time, that he essentially handed Murnau a blank check and let him have at it.

F.W. Murnau was brought to Hollywood from Germany by William Fox and given carte blanche to make his film. Fox had been so impressed by 1924’s The Last Laugh, its sweeping long-takes and Expressionist superimpositions so different from the Hollywood productions at the time, that he essentially handed Murnau a blank check and let him have at it.

Sunrise was the result. The film was not a hit, but it was lauded by critics and showered with prestigious accolades at the first Academy Awards, so it seems Fox made the right call.

The film’s narrative is intentionally painted in broad strokes, a point underlined in the opening intertitle: “This song of the Man and his Wife is of no place and every place; you might hear it anywhere, at any time.” No character is named, and even the location is anonymous — it could indeed be happening anywhere. This same sense is reinforced through a hybrid production history, as famed cinematographer Nestor Almendros once pointed out:

[T]he script was written in German, and even the sets were already designed in Germany by Rochus Gliese. This is why Sunrise is such a hybrid movie. The city looks like nowhere on earth; one wonders in what country it could be located. The landscape and the people – what are they? American? German? Scandinavian? It doesn’t matter, for Sunrise is a fantasy, not realism; there is stylization in every scene, and that hybrid quality contributed to the stylization.

The plot can be summed up quickly. The Man (George O’Brien) is spurning The Wife (Janet Gaynor) to carry on a tryst with The Woman From The City (Margaret Livingston). Livingston’s vampish, urban femme fatale talks O’Brien into murdering Gaynor, selling his farm, and living it up with her downtown, trading livestock for nightclubs and adventure. He tries to do so but can’t follow through, struck with remorse and self-horror. The Wife is terrified but eventually forgives him for the minor transgression of trying to drown her.

Instead, the two embark on a joyous, whirlwind tour of the city themselves, a free-spirited lark that doubles as a second honeymoon, with The Man and The Wife frolicking like young lovers. But, irony of ironies, their little boat in fact does capsize on the return trip. The Wife almost drowns but is saved at the last moment. The Woman From The City is vanquished and flees. The married couple are born anew, as the sun rises over their conjugal bed. It is a new day.

This is a narrative that manages to be both sentimental and offhandedly callous, but Sunrise is not a film primarily concerned with plot. Murnau marries German Expressionism with this fairy-tale boilerplate — and an incongruous comic set-piece involving a runaway piglet drunk on wine for good measure, perhaps a concession to American audiences — and emerges with something entirely different. Sunrise is a dreamscape of country and city, innocent blonde and nefarious brunette, torrential rains, capsized boats, anxieties made visible as ghostly superimpositions.

And everywhere, everywhere movement. There is hardly a mode of transportation that is not emphasized, as The Man and The Wife row boats, jump trolleys, nearly get hit by whizzing cars, jump out of the way of horse-drawn carriages, attend a fair where roller coasters and rides animate the back of the frame. This constant motion adds a futurist vitality to the goings-on, with deep focus shots created through the insertion of smaller sets in the background of the larger ones, and inventive strokes, in the absence of wide lenses, like dressing children in adult clothes and placing them in the distance to suggest depth.

The camera dollies and free-flying tracking shots are probably the most celebrated aspects of Sunrise, particularly in the famous sequence depicting the couple’s entrance to the city. In unbroken takes, Murnau allows the camera to track their movement from trolley to street. A mass of cars seems to threaten imminent death, but the two are so lost in their shared reverie that the entire visual world shifts, suggesting that, in their minds, they are out for a stroll in the quiet countryside. It’s an enormously neat trick.

When The Man and The Wife stumble across a marriage ceremony, during which he tearfully realizes the gravity and barbarity of what he had almost done, the production design uses smoke to allow light from a high window to filter through in beams, illuminating the inside of the Church (in much the same way Murnau accomplished during a similar moment in his Faust). Legendary cinematographers Charles Rosher and Karl Struss apparently ran tracks on ceilings for overheads. The cityscape set alone was reputed to have cost an incredible $200,000. No expense was spared or idea disallowed, and it shows.

O’Brien and Gaynor both turn in accomplished performances: his frequently hunched shoulders suggests the weight of the world (or something more sinister from a horror film), and her hesitations, fear, and ultimate joy in reunion are more believable than it would seem the plot would allow. Livingston, given less to do, fairs less well, but she ably conveys the kind of citified cynicism her character embodies.

Released the same year as The Jazz Singer, the American version of Sunrise came with a dedicated score (Gounod’s “Funeral March of a Marionette”) and a handful of synchronized crowd and animal noises (for instance, during the dreadful “comic” interlude involving the escaped pig). Audiences abroad would’ve seen it with live music and none of that, which was probably preferable.

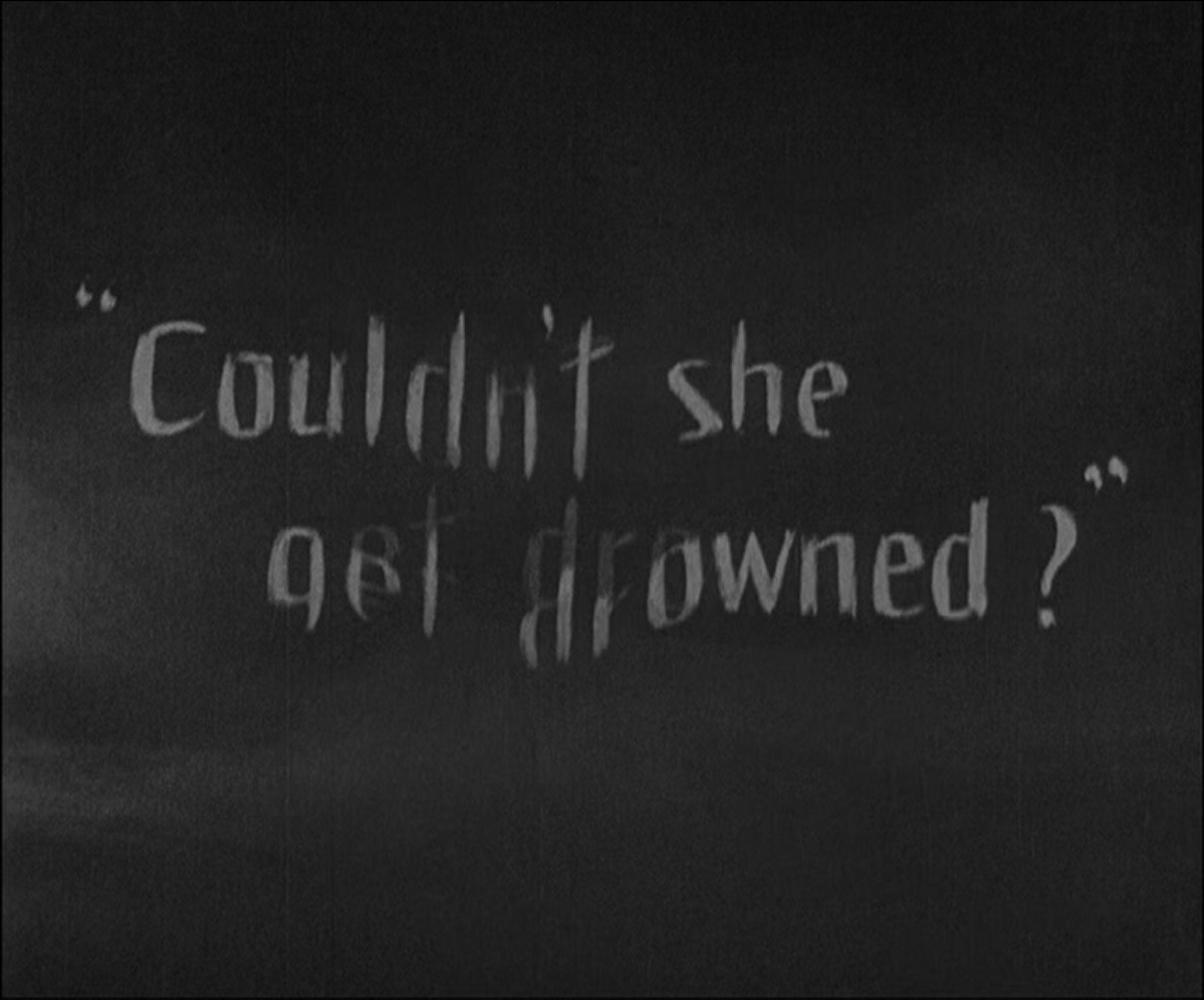

After all, Sunrise is visual spectacle first and last. Murnau didn’t even want intertitles but relented, and, appropriately enough, turned many of those into signifiers anyway; the title card below employs a typical Expressionist technique to simulate linguistic meaning through image:

Despite its narrative shortcomings, Sunrise finds a master of the silent era employing every trick he knows, with a nearly unlimited budget and the full support of an early studio system. It’s a masterpiece, even if it does suggest that trying to kill your wife might be the best thing for your marriage.

It’s very broad melodrama, and the realism of spoken dialogue would have made it impossible. But silent films were more dreamlike, and Murnau was a genius at evoking odd, disturbing images and juxtapositions that created a nightmare state. Because the characters are simple, they take on a kind of moral clarity, and their choices are magnified into fundamental decisions of life and death.

I imagine it is possible to see “Sunrise” for the first time and think it simplistic; to be amused that the academy could have honored it. But silent films had a language of their own; they aimed for the emotions, not the mind, and the best of them wanted to be, not a story, but an experience.