Metropolis is indisputably one of the most celebrated films of the Silent Era and the generally agreed-upon cinematic pinnacle of Weimar. A dystopian sci-fi landmark distinguished by incredible set design and in-camera tricks, director Fritz Lang’s monumental ode to “the heart” as the “mediator of head and hands” was hugely influential on dozens and dozens of films to follow.

It is also not very good.

Is this heretical? Critics at the time, including voices as different as H.G. Wells and Buñuel, tended to agree, and Lang himself had this to say in 1965:

I have often said that I did not like Metropolis and this is because I can’t accept today the leitmotif of the message of the film. It is absurd to say that the heart is the intermediary between the hands and the brain, that is, of course, between the employee and the employer. The problem is social and not moral. Naturally, during the shooting of the film, I liked it, if I hadn’t I couldn’t have continued to work on it. But later I started to understand what didn’t work. I thought, for example, that one of the faults was the way I had shown the work of the man and the machine together. You remember the clocks and the man who works in harmony with them? He became, so to speak, a part of the machine. Well, that seemed to be too symbolic, too simplistic in its evocation of what is called “the evils of mechanization.”

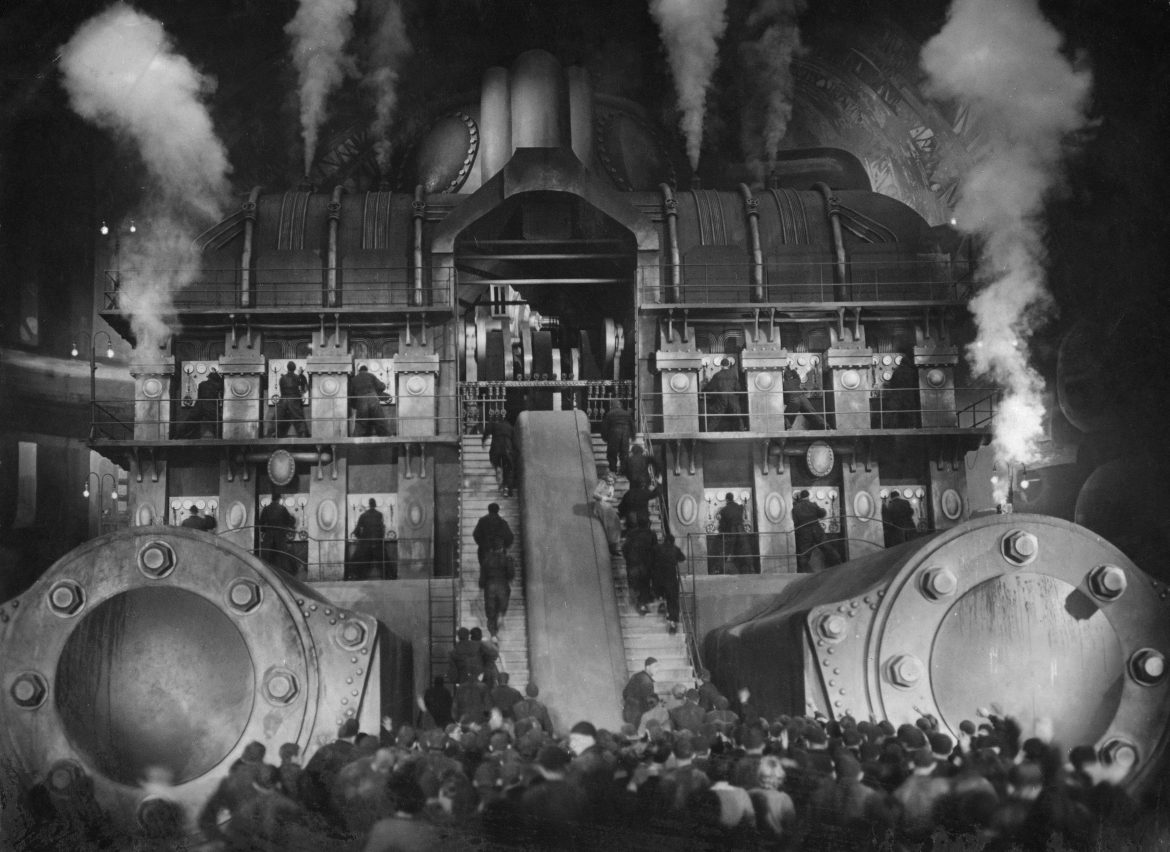

Still, there’s no denying the film’s staggering production design and influence on everything from Brazil to Star Wars to Blade Runner to Alphaville to, well, basically everything that imagines a future city of towering structures or any film featuring a crazy-haired mad scientist flailing about in a lab somewhere.

The story is almost embarrassing in its naivete to relay, but here goes. In the future, the city of Metropolis is divided between the opulence and decadence of an above-ground playground for the rich and a subterranean hellscape where workers toil in anonymity and suffering. Freder, son of the city’s architect ruler Fredersen, discovers that his pleasure is rooted in the pain of the workers and seeks to help their lot, with the assistance of a salvational figure in the form of Maria. However, the workers await the arrival of a Messiah / Mediator who will lift them up and ameliorate the disconnect between rich and poor. With an impressive lack of humility and more than a touch of sexism, Freder decides he will be that Messiah, not Maria.

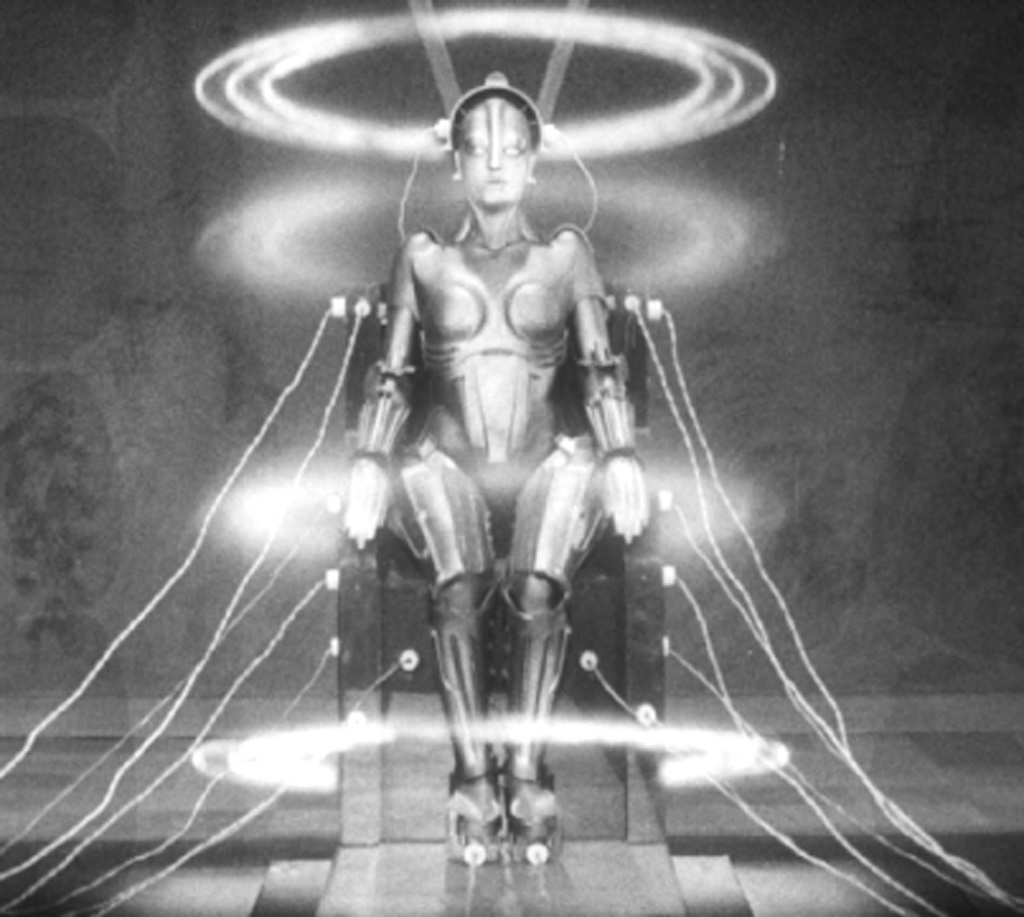

Meanwhile, in an attempt to hold on to power and further the subjugation of the masses, Fredersen turns to mad-scientist Rotwang, who has been working on robot technology. They kidnap Maria and make a figure in her likeness, an anti-Maria who will foment discord among the workers and bring them to their own ruin through revolutionary, Luddite-like incitement, via hip gyrations. In a startling tableau, Lang communicates the intoxicating visual effect on the workers through superimpositions of eyes, as False-Maria’s sexuality rerouts desire to destruction:

The plan doesn’t work, ultimately, and the ruse is revealed. Fredersen has a change of heart, Freder literally unites the two classes in mutual harmony, and all is right with the world, which presumably goes right back to the status quo.

There’s little point in explicating how little sense any of this makes. What’s really striking is the way in which Metropolis has often been remembered as itself somehow revolutionary.

Quite the opposite: although depicting extreme class stratification, its narrative hinges on the desirability of such separation, which is probably one of the reasons it was so popular with the Nazi Party that Lang’s then-wife and co-writer Thea von Harbou would go on to enthusiastically support. Indeed, Metropolis boasts the dodgy honor of being Hitler’s favorite film. As Michael Atkinson notes:

The statement about class warfare made by the film’s visual gigantism and visions of humans fed into the furnaces at a radical disconnect from the story’s play-nice denouement. Will the workers just go back to the caverns and man-eating generators? In fact, when the villainous anti-Maria yowls “Death to the machines,” she speaks the people’s truth. The problem is, this was just 10 years after the Russian Revolution shocked and horrified every government leader, CEO and aristocrat on the globe.

Which is why Metropolis, a film that ostensibly sympathizes with the workers, had to be an anti-revolutionary narrative–in the shadow of the Bolshevik uprising, a dystopia that maintained clear class separation in a civil manner seemed to be a desirable alternative. For the filmmakers and the Nazis who loved them, Metropolis was a massive turbine built to provide a negative charge against Soviet propaganda, and to idealize the top-down social model quickly constructed out of National Socialism.

I have focused largely on the politics of Metropolis because they are so central to both its narrative and critical reception. Aesthetically, of course, the film is a miracle, blending Art Deco architectural visions and a kind of manic Futurism with the externalized psychologies of its characters, in the typical German Expressionist fashion that Lang mastered.

Metropolis is the epitome of visual splendor at the service of weak, borderline incoherent storytelling. The 2008 discovery of missing reels in Buenos Aires helped clarify some things, as well as revealing the film to be more of a meshing of genres than the pure sci-fi film its often considered, but nothing can really alter the fact that Metropolis is, as H.G. Wells indelicately alleged, “silly”. Of course, the same has been said of the Star Wars films, a series it very much influenced, and those seem to have done pretty well with audiences over the years.

Still and all, Lang and his crew’s technical achievements were substantial, and Metropolis remains one of the most visually stunning films ever made. That’s something.

The result was astonishing for its time. Without all of the digital tricks of today, “Metropolis” fills the imagination. Today, the effects look like effects, but that’s their appeal. Looking at the original “King Kong,” I find that its effects, primitive by modern standards, gain a certain weird effectiveness. Because they look odd and unworldly compared to the slick, utterly convincing effects that are now possible, they’re more evocative: The effects in modern movies are done so well that we seem to be looking at real things, which is not quite the same kind of fun.