There’s always something a little jarring, a little suspect about revisiting an artist’s early work. The impulse is to read the texts as prologue: what is to come. So, if David Cronenberg’s first foray into filmmaking — the 1966 short Transfer, made when he was just 23 years old — is (what’s the word?) “bad”, at least it can be recuperated by identifying the tendencies that will animate later, more accomplished films.

I’ll be doing some of that here, at least in part because there really are interesting aspects of a gestating auteur. But art should also be encountered where we find it, on its own terms. And let’s not shit ourselves: the overwhelming majority of Beckett-inspired, handheld movies from 1966, conceived by 23 year olds and cast with non-actors, are just not going to be classics for the ages. Cronenberg’s debut is no different.

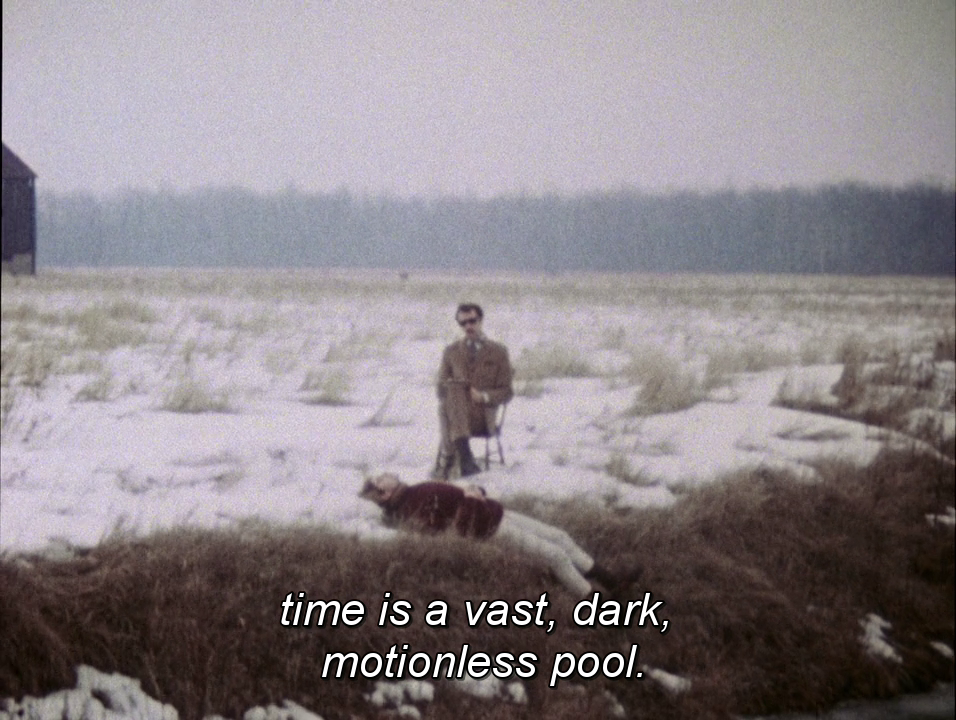

In Transfer, Cronenberg presents a psychoanalyst and a patient who’s been stalking him. We get the sense that the analyst lives outdoors, in snowy fields or by ramshackle structures, where he and his undesired companion eat dinner and argue. Cronenberg himself called it a “surreal sketch,” noting, “The only relationship the patient has had which has meant anything to him has been with the psychiatrist.”

In Transfer, Cronenberg presents a psychoanalyst and a patient who’s been stalking him. We get the sense that the analyst lives outdoors, in snowy fields or by ramshackle structures, where he and his undesired companion eat dinner and argue. Cronenberg himself called it a “surreal sketch,” noting, “The only relationship the patient has had which has meant anything to him has been with the psychiatrist.”

We are already in the realm of his later films, including Stereo, The Brood, and Scanners (to say nothing of A Dangerous Method‘s literalism, or the patient/charismatic figures of Videodrome or Dead Ringers). From the start, there’s a wellspring of suspicion about the authority of charisma and psychoanalysis, an idea of a symbiotic relationship between host and virus (to use Cronenberg’s preferred metaphor), and the role language has to play in all of this confusion. There’s even a sense of the encroaching visceral, mostly through dry-wit jump-cuts and uncomfortable frames.

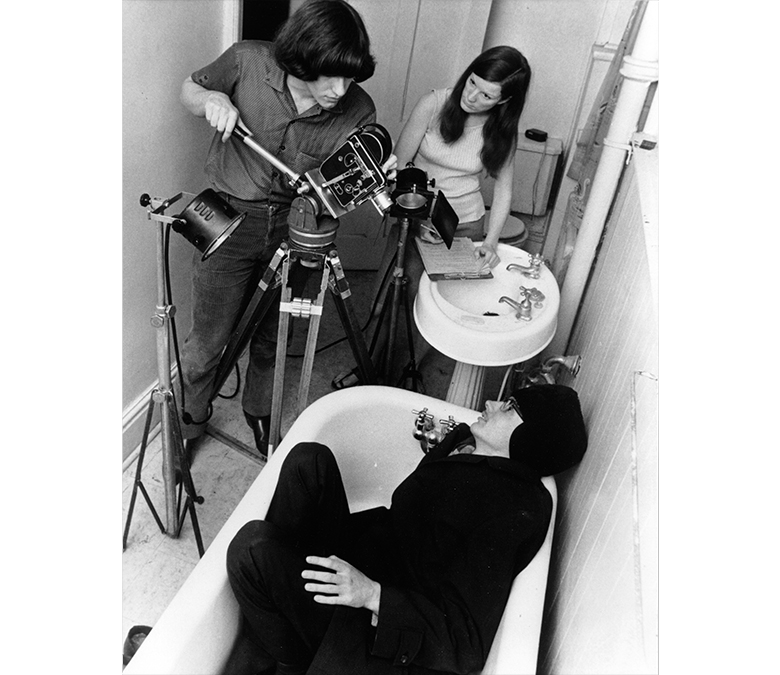

With From The Drain, released the following year, we start to recognize the Cronenberg who will come to the fore. If Transfer is a first-attempt at absurdist parable, From The Drain is full-on experimental goofball horror, or at least what a 24-year-old director might consider as such.

Focusing on two war veterans who find themselves in a bathtub together, and a possibly imaginary plant-like creature whose tendrils pose existential threats, From The Drain is a curious little number, a spec-script oddity that only barely survives its amateurish performances and murky shadows.

Still, that summary alone conjures up a bit of the weirdness that will define Cronenberg’s work, once the stagy self-consciousness, Brechtian and Godot-like emphases, and “who needs pacing?” sensibilities are jettisoned. His later films are sometimes considered almost mannered to a fault; no one will accuse From The Drain of that sin, anyway, regardless of its failure or success on its own terms.

In both these early shorts, one also gets the sense of a very mid-60s approach to no-budget transgression. If they both aim for something Persona-like in their depictions of role reversals and the uncanny, they also both lack anything like Bergman’s sheen, for obvious reasons.

Nor is either film particularly good; in fact, parts of From The Drain are nearly unwatchable in their current state of disrepair, though that may have as much to do with the performances as the 16 mm film stock.

But as artifacts, they’re pretty fascinating: even as a youngster, we find someone engaging with both the work of his time and some pet obsessions that will only get more intense over the years. The combination of twinning, psychoanalysis, dangerous proximity, and transformation will all be hallmarks of Cronenberg’s career.

This is the first in a film-by-film series examining David Cronenberg’s work. Next up: Stereo.