Peter Greenaway has long been an arthouse staple, his background in painting evident in nearly every carefully considered frame. His cockeyed narratives (along with their ubiquity of actual cocks) have made him celebrated and divisive in equal measure, and Eisenstein in Guanajuato is arguably the British auteur at his most divisive, and definitely his most breathless.

A feverish imagining of the Russian master’s 10-day stay in Mexico, officially capturing footage for his unfinished ¡Que Viva México! and unofficially rethinking his relationship to making films at all, Greenaway envisions this period as one of radical transformation amid the mummies, decadence, and glimpses of new possibilities.

(Spoilers to follow)

Liz: So, Rick, this is the first time we’ve done one of these discussion pieces on anything not recent, and Eisenstein in Guanajuato probably looks like a bit of a random choice. I think I had had Greenaway on the brain for a while, and had never gotten around to actually watching one of his movies (other than The Falls, which is a totally different Python-esque thing that I love). I had kind of set up a mental picture of Greenaway as a schoolboy, very proud of how clever he is and how much he knows, but that didn’t really set me up for how exhilarating this movie is. It really is a rush of a movie, bolstered by a completely manic performance from its Eisenstein.

Liz: So, Rick, this is the first time we’ve done one of these discussion pieces on anything not recent, and Eisenstein in Guanajuato probably looks like a bit of a random choice. I think I had had Greenaway on the brain for a while, and had never gotten around to actually watching one of his movies (other than The Falls, which is a totally different Python-esque thing that I love). I had kind of set up a mental picture of Greenaway as a schoolboy, very proud of how clever he is and how much he knows, but that didn’t really set me up for how exhilarating this movie is. It really is a rush of a movie, bolstered by a completely manic performance from its Eisenstein.

What did you think of it, and what did you expect of Greenaway coming in?

Rick: My familiarity with Greenaway — with actually watching his films, I mean — is cursory at best. Prior to this, I’d only seen the Greatest Hits duo of The Draughtsman’s Contract and The Cook, The Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover. So I had a general notion of his painterly compositions and enthusiasm for scandal, but not much beyond that. My familiarity with Greenaway-as-person-you-should-know-about, on the other hand, was much more robust, so he’s always felt like something of a blind spot.

Neither of those earlier, more celebrated films prepared me for Eisenstein’s manic energy at all, though. If anything, my mental Greenaway was much more sedate and studied, and definitely less enthusiastic about triptychs, 360 degree pans, and 10 minute-long still shots of extraordinarily chatty anal sex. I found it a surprising and daring “history” of an icon. What led you pick it?

Liz: Actually, I have to admit a slight fib: I realized a few minutes into it that I had started it years ago, when it came out, and never made it more than fifteen minutes in. So, I suppose it’s been swimming in my mind ever since then, waiting to be re-watched.

I want to ask a question that I also don’t want to ask, because it’s a question that usually shows up in the reviews of mediocre film critics unprepared for an art house movie. That question is: What do you think Greenaway is actually doing here? It’s a terrifically fun movie to watch – we are zipped around from scene to scene both by some lunatic direction and Elmer Back’s lunatic performance as Eisenstein, and it was interesting to imagine Eisenstein as a real homosexual in a horribly tough situation. (I don’t know how much of this film is actually true, particularly its closing intimation that Eisenstein was murdered by the Stalinist authorities.)

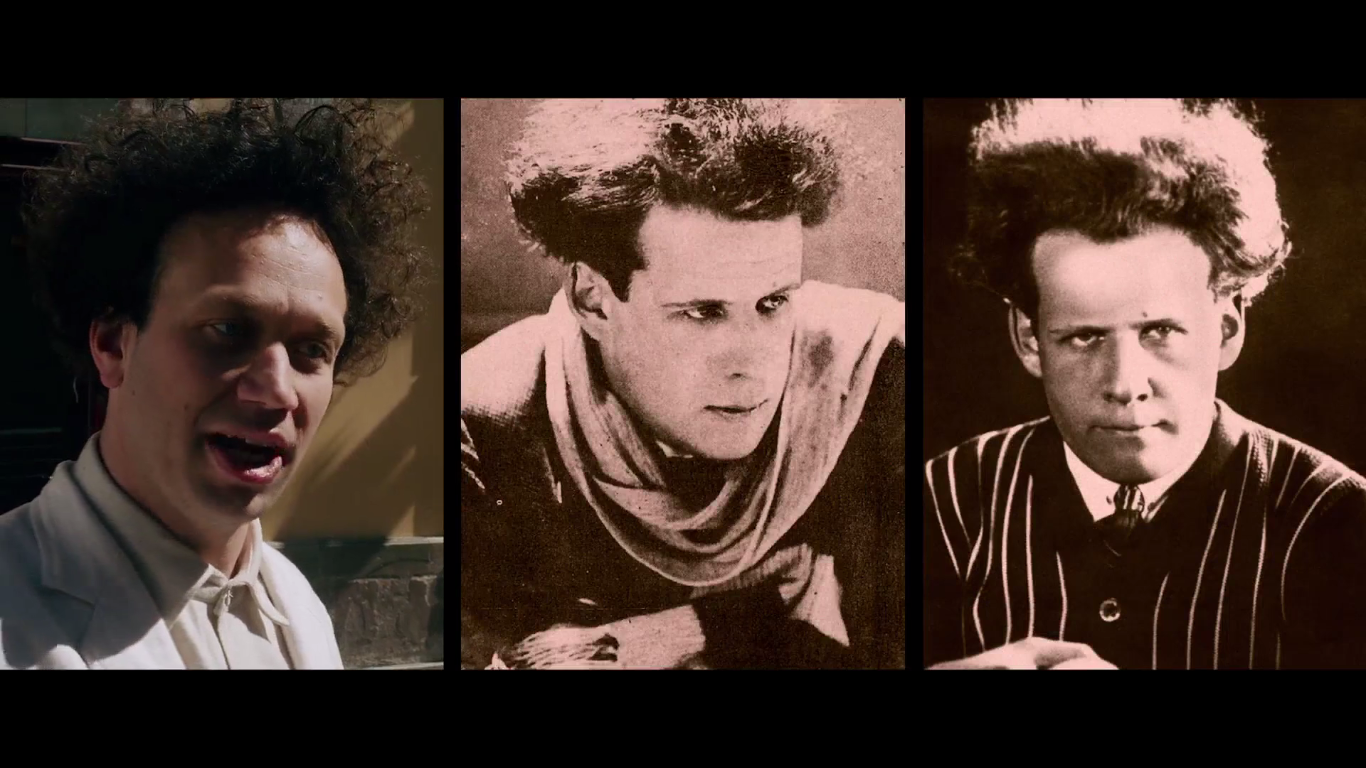

But is he saying something about Eisenstein as an artist? Or about film in general? About a relationship between film and homosexuality? Or the film world at the time? (Other movies like Argo wait until the credits to show you what the real people looked like, compared to the actors; Greenaway just pops real photos up whenever he gets the chance.)

It was a terrific experience and one I would have again, even if there’s no “comment”, but it feels like there must be one and I can’t quite figure it out.

Rick: Eisenstein is so exuberant and draws so much attention to itself, both formally and as a kind of playful re-imagining of a major player in film history, that I think it’s pretty much impossible to avoid asking what it’s all about!

Rick: Eisenstein is so exuberant and draws so much attention to itself, both formally and as a kind of playful re-imagining of a major player in film history, that I think it’s pretty much impossible to avoid asking what it’s all about!

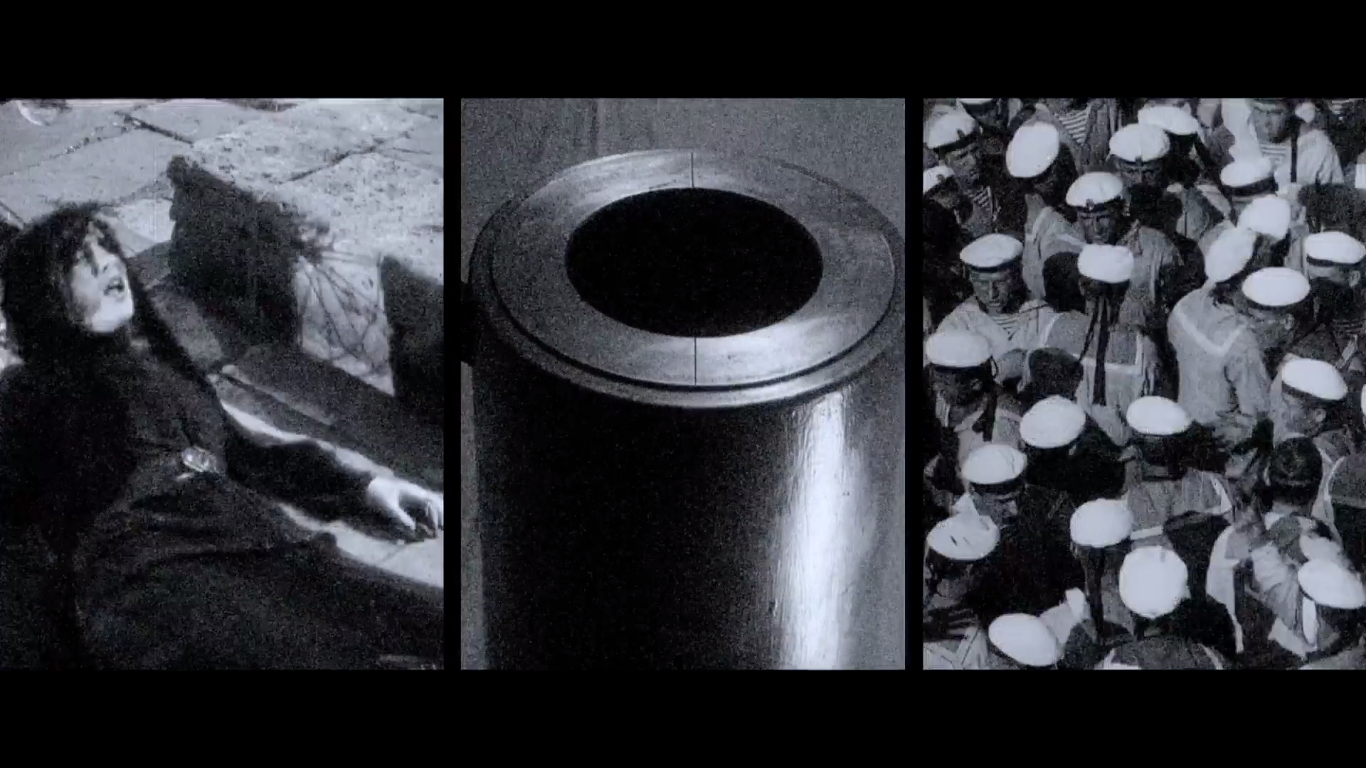

In grappling with it, I think it would be helpful to first just tick off some of its most prominent formal features. Eisenstein himself is inextricably bound to the very idea of the montage — if you somehow ended up with “montage” as your word on a particularly cinephile-heavy episode of The $25,000 Pyramid, you’d have to start with “Eisenstein” — and Greenaway deploys plenty of them here. But he also finds time for those 360 degree revolving shots, the repeated division of the screen into thirds, scrolling transitions, archival footage, historical photographs, hyper-digital tableaux, ostentatiously long takes, and more. They seemed to be battling for space on the screen, and the main feeling I got was excess. It all just kept coming.

Eisenstein paints its protagonist’s Mexican sojourn in a number of different shades, but a recurring theme is a focus on Mexico as a land of sex and death (or, as the film baldly states, Eros and Thanatos). There’s a sense of transition or escape — both from the perceived dead-end of Soviet filmmaking (and its glorification of the montage) and the false promise of Hollywood freedom, hamstrung by capitalist demands and the political climate … not to mention from heterosexuality and repression. The explosion (and diversity) of Greenaway’s formalism seemed tied into all of this, like someone’s image-bank and technique overflowing with new possibilities, at least for a time. Did you get this same sense of excess?

Liz: Oh, absolutely. And I would say in some ways it’s an expansion of silent montage excess, but to everything. I’ve always found Eisenstein’s film theory a little impractical, a little separated from my actual experience of watching even one of his films, but that sense of something larger appearing because the individual parts are flashing by too quickly to keep track, of something dialectically larger emerging out of the parts, is here.

The triptychs in particular are an interesting choice. The natural impulse would be to shoot a movie about Eisenstein in the Academy ratio, and that’s a self-consciously “clever” choice Greenaway doesn’t make. But then he emphasizes that widescreen ratio by dividing it into thirds. For me it brings to mind Cinemascope and Napoleon, not Eisenstein — it’s an interesting choice I can’t quite figure out.

There’s also the hyper-digital stuff. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything quite like it: he has the camera spin around in decentering ways in these digital spaces, where the figures look openly, weirdly fake. And all that is lit in an garish way that is really eyebrow-raising. I actually had to look up more than once, to make sure that this wasn’t originally shot in 3D or something. It’s a very strange choice.

I also do want to comment on how much I loved the performances here. Not just Elmer Back as Eisenstein, who I’ve mentioned already (I sincerely want to know what Greenaway told him to get this performance out of him), but also the man who plays his guide-turned-lover, Luis Alberti. There are a lot of terrifically large performances here, and Alberti finds some terrific ways to wiggle through the giant personalities with a real cat-like way of walking and talking. I really thought he was terrific, especially since both he and Back are essentially unknowns (at least outside their country, but it seems inside it as well).

I also do want to comment on how much I loved the performances here. Not just Elmer Back as Eisenstein, who I’ve mentioned already (I sincerely want to know what Greenaway told him to get this performance out of him), but also the man who plays his guide-turned-lover, Luis Alberti. There are a lot of terrifically large performances here, and Alberti finds some terrific ways to wiggle through the giant personalities with a real cat-like way of walking and talking. I really thought he was terrific, especially since both he and Back are essentially unknowns (at least outside their country, but it seems inside it as well).

What did you think of the performances?

Rick: Well, like you said, Elmer Back’s version of Eisenstein — a naif and aesthete who seems to have recently consumed all the coca in the region — is pitched at something approaching lunatic frenzy, and Alberti plays the Suave Libertine in the most charming, seductive way possible. They’re both great. But at a certain level — and this might sound weird to say about performances that take up so much space — the performances themselves seem almost beside the point, at least as individuals.

They seemed so big and so self-aware that they actually faded into the structure of Greenaway’s project instead, like allegorical figures or what David A. Gerstner, in the Los Angeles Review Of Books, called “actor-’types,’” comparing their depictions to “the masks worn in Japanese Nō Theater”. This is similarly true of Eisenstein’s American financiers, or the Mexican bandits lurking around. I read a critical review in which the writer faulted Back for speaking with a distinctly un-Russian trilling of his rrr’s, which — while 100% true — struck me as spectacularly beside the point. You may as well complain that Eisenstein never made cross-continental phone calls in the shower.

But back to this question of excess. Derek Jarman, whose Wittgenstein I couldn’t help thinking of and who is often (despite his protests) discussed together with Greenaway, identified it in Eisenstein’s films as “the area of magic as metaphor for the homosexual situation.” In that same LARB piece, Gestner wrote that this film

takes it upon itself to give cinematic expression to Jarman’s phrase insofar as Greenaway’s cinema aestheticizes Eisenstein’s montage, broadly conceived, by concretizing Eisenstein’s “homosexual situation.” Folding cuts into mise-en-scène and mise-en-scène into cuts, Greenaway rewrites Eisenstein’s “montage of collision” as the “montage of penetration.” In short, he homosexualizes Eisensteinian montage.

What do you make of that, or of the extremely prominent foregrounding of queerness in Eisenstein’s aesthetic more generally?

Liz: Hmm… I suppose I can see it. I can see the idea that he is somehow expanding or realizing Eisenstein’s dialectical imagery, that the two images inter-penetrate each other, but I’m not entirely certain I see it relating to Eisenstein’s homosexuality here. And that’s definitely partly because I’m a bit exhausted of the idea of “queering” in academic writing, and tend to resist it unless I see a pretty clear line of development.

Liz: Hmm… I suppose I can see it. I can see the idea that he is somehow expanding or realizing Eisenstein’s dialectical imagery, that the two images inter-penetrate each other, but I’m not entirely certain I see it relating to Eisenstein’s homosexuality here. And that’s definitely partly because I’m a bit exhausted of the idea of “queering” in academic writing, and tend to resist it unless I see a pretty clear line of development.

Is there a “queer”ing (to use I think the more rigeur term) of Eisenstein’s dialectical ideas here? I suppose there is something to that, to the extent that the dialectic in general assumes a very heteronormative idea of the descent of generations: ideas battle and battle and at some point in the far future our children’s children’s children will get to Absolute Spirit (or the dissolution of the State, or the true aesthetic ideal…) And this film does play with the idea of descendents, especially with its ending, when Eisenstein’s lover’s wife pleads with him to lead his lover return to her and his sons.

I suppose I might be talking myself into agreeing with that idea — a kind of dialectical-cinema-as-camp argument. It would also, in its way, recapture a live Eisenstein from the dullness of both formalist film history and the Soviet film history.

But also I think this all is kind of resting on a simple play on “penetration”, and I’m not sure penetration is the word I would use for the aesthetic itself. (Although, if we want to go back to its foregrounding of the widescreen format … We might expand Fritz Lang’s line from Contempt: Widescreen is only good for shooting funerals, snakes, and hard-ons.) It’s more of an act of folding, I think, questioning the “one, then two, then they somehow combine to make seventeen” imagery of Eisenstein’s actual dialectic into “one and two, at the same time, a fluid transition from one to two that brings to mind seventeen”.

I don’t know. Can you maybe expand a little on how you interpret that quote around the film?

Rick: I’m don’t really know, either! It just seems very clear that Greenaway is establishing all these linkages between montage and homosexuality, and Jarman’s idea of magic-as-metaphor provides some kind of clue. There is also the idea of masks, so central to Eisenstein‘s Day of the Dead climax (as it were): that montage, reportedly according to a “cynical” Eisenstein in pubs after lectures, was arrived at “to cover up the fact that half the time they didn’t know what they were doing when they were obliged to work with short ends of film.” Gestner finds in this (pretty dubious) admission an “epistemology of the closet,” another link between a structuring aesthetic and a developing politics beneath the overt one. All of this is speculative, in a lot of ways, but Eisenstein is hilariously, self-consciously speculative through and through, so it doesn’t seem inappropriate to play around with its ideas.

We’ve gone down a pretty heady road here, though, and it’s not like Eisenstein is a dry treatise! It’s extremely wacky and enjoyable, in fact, with more striking images in any given ten minutes than most films conjure up in two hours. It’s definitely one I’ll return to, even if I’m not sure I’ll ever “figure it all out”. Who would want that anyway?