Blade Runner — 1982’s Ridley Scott-directed, Hampton Fancher-penned sci-fi classic — wasn’t immediately received as the resolutely grimy masterpiece of a Philip K. Dick adaptation that fans now cherish.

The New York Times went with “muddled yet mesmerizing,” complaining that Scott “expect(s) overdecoration to carry a film that has neither strong characters nor a strong story,” for instance, and Roger Ebert, in an otherwise positive review, concluded “[T]he movie has the same trouble as the replicants: Instead of flesh and blood, its dreams are of mechanical men.” Reports at the time detailed a rocky road to release, but its genre esteem has skyrocketed since then, beyond even the usual “cult classic” moniker. For many viewers, Blade Runner is a classic-classic, full stop.

35 years later last month, Blade Runner 2049 arrived, with celebrated director Denis Villeneuve at the helm, the great Roger Deakins bringing his particularly elaborate visual acuity to the production, and Fancher (recently the subject of a pretty fascinating documentary) returning to update the original.

Celebrated by many as a worthy successor and panned by more than a few others, who have seemed collectively determined to reinsert the word “turgid” into the critical lexicon, the sequel is doing modest, if somewhat disappointing, business (though it hasn’t opened in China or Russia yet).

How do its themes hold up 3 decades later? What does the franchise’s emphasis on humanness, identity, and artifice mean in 2017? Leaving aside the narrative dimension within the film, is Ryan Gosling actually a robot in real life? Our team discusses this and more.

(Spoilers to follow)

Liz Lundberg: So, Rick, a couple weeks ago we were anticipating that I’d like this movie a lot more than you, given your distaste for Denis Villeneuve, but now I’m not so sure. So I guess I should ask: what did you think?

Rick Kelley: I should admit at the outset that, along with not being much of a Villeneuve guy, I’m also not a particular Blade Runner enthusiast. I mean, I’ve seen the original more than once, but it’s never been something I’ve returned to as a cinematic or cultural touchstone, like a lot of folks I know. If I’m being really honest, I fess up to barely understanding the story, unless it’s explained to me as though I were a very young child. To me, the visuals and atmospherics, the world-building, overpower everything else to such a degree that it’s hard to even tell what’s going on half the time … but those visuals and atmospherics are so intricate and attention-grabbing that they make up for what seems like a lack of coherence.

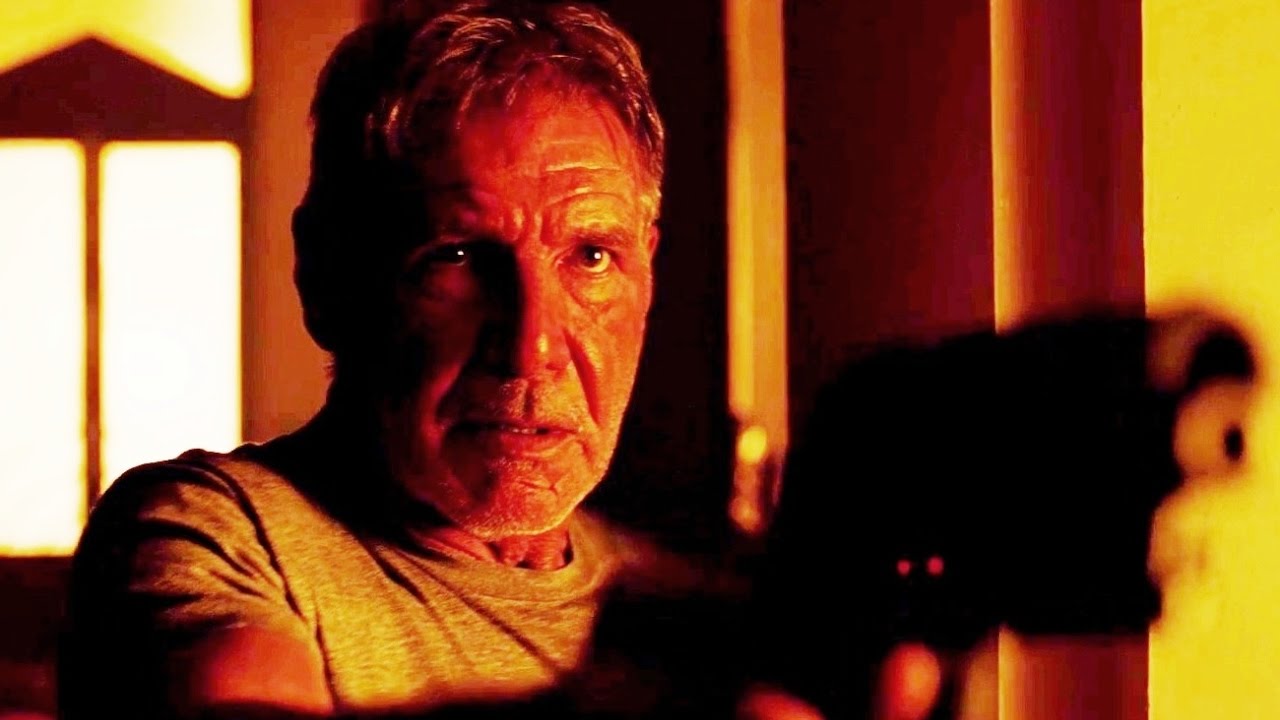

And on that score — the pure, oh-shit artifice of the image, and the ways it thematically echoes what plot aspects actually did land in my pea brain — I liked the newest iteration just fine. There are some staggering set-pieces throughout, and, apart from a weird affinity for overpowering orange-ness, Deakins especially is in top form here. It’s the rest of the movie I’m struggling to appreciate.

How did the experience strike you?

L: I’ve seen Blade Runner a few times and like it pretty well. Even if the style of the world doesn’t capture the deadly serious cartoonishness of the PKD original, the tempo of it matches the book for me. Everything is off-kilter and the lines are timed a little off, a little too close together.

I was interested in this movie as more of an homage to the original than a real sequel, since most of what is here as a direct connection could come from any movie about robot-based societies – up until Harrison Ford showed up. I’m not going to lie, I thought Ford was terrible in this. It doesn’t seem to me like there’s any connection between the Rick Deckard here and the one in the original film. I mean, the way they try to act like it was love at first sight between him and Rachael, when in the original he keeps referring to her as “it” for the rest of the scene, is just bizarre.

On the other hand – and this sounds more like an insult than it is meant to be – Gosling might have been born to play an emotionless robot. It’s interesting to contrast him to the sexual and mostly queer-coded robots of the original. What did you think of the performances?

R: If it weren’t for his more charming outings — the ones where he shows some development from lab-constructed automaton to something approaching a real boy, usually with the assistance of Emma Stone — I would be entirely unsurprised to find out Gosling really is an emotionless robot. I mean, have you seen Only God Forgives? Here, I never once believed in Blade Runner 2049’s character MacGuffin, because, c’mon … take a look at the guy. That’s not an actual human. All of which worked for the material, actually.

I strongly agree about Ford’s Deckard, who seems to have walked in from another film in which he is not the villain. I suppose a generation out in the Sinatra-scored, statues-of-Ozymandias-strewn wasteland could’ve prompted some self-reflection, but it felt like a leap I wasn’t prepared to make.

Curiously, for a film that sometimes seems mired in toxic masculinity, the women made the larger impression. Sylvia Hoeks owns every scene she’s in, I thought, and even Ana de Armas (as Joi) makes some interesting choices. (Though they were more interesting when the film was called Her.) But since you bring up both the starry-eyed Rachael fan service and the “mostly queer-coded robots” of the original, what did you think of the sexual politics here? I found it troubling for a variety of reasons.

L: People to whom I’ve complained about the really weird presentation of Deckard here have pointed out that a guy can grow over the interim period, and I suppose they’re right. But, one, if that happens it has to be presented dramaturgically. Han Solo can’t just show up as a completely different dude and not have us notice the difference, you know? (Alternatively: Mr. President can’t show up in the inevitable Air Force One sequel and suddenly want bad guys to get on his plane.)

And more importantly: if he has grown and changed, why does he seem to show zero remorse about all the robots he murdered as a blade runner? Man, they really let you change allegiance fast in the revolution! I mean, they had a perfect place to bring it up, when they’re sending K to assassinate him, as opposed to that weak-ass “he knew what he was signing up for” argument that felt to me like an easy pitch to end the film on more humanitarian liberal morals than leftist revolutionary ones. (There’s a hint of “the revolutionaries are just as bad” once Ford shows up that is very dumb and reminded me of Bioshock: Infinite. (Rick, I know you don’t play video games, so you don’t know this is a very bad thing.))

Anyway, regarding the sexual politics, I wonder if we’re on the same page about this, because I thought they were very weird, too. There are definitely very queer tones to the original, in that Deckard is this very dull heterosexual dude contrasted with the weird sexual energy of the replicants – particularly in the last half hour or so. (Only a very heterosexual dude could pull off the most insane scene in the original, where Deckard pretends to be a morals inspector searching a stripper’s dressing room for peepholes. If you don’t remember it, go find it – it’s hysterically weird.)

And this drive for a longer life, for finding meaning in one’s own life as opposed to having kids and building this chain of memories from generation to generation, very much resonated, I think, in the AIDS-scare era. So to have the replicants all now find the possibility for rising up and claiming value because they can have kids? That all felt extremely, extremely weird.

Is that where you were going with it?

R: Very much so, though you hit on points I hadn’t considered. (Particularly the relation of baby-making to the shame of that era’s foray into AIDS-scare discourse).

I suppose I found it very odd that fertility itself is the end-game. In a film universe like Blade Runner, so consumed by questions of human-ness and its ambiguity — which is just to say, in some ways, sexuality — it seems a deeply reactionary element to guide a Revolution, particularly one founded on hybridity. The existential questions K. grapples with and dies for — also, can we just briefly mention that his name is effectively Josef K.? Ok, that’s done, moving on — don’t seem like they’d be resolved by a Children of Men-style salvational infant in the techno-manger. I do agree with Todd van der Werff that Villeneuve and Fancher cleverly dodged one bullet on the Chosen One narrative, but it seems like they just jumped in front of another one instead.

I’m also trying to get at a lingering unease I share with my friend Chris Osmond, who catalogs the extensive violence women undergo throughout the film. I am not squeamish, and much of it serves a narrative function, but there’s a particular vision of the female body presented here as a site of suffering and redemption that feels off, even lazy, and even, possibly, malicious. The disembowelment that echoes Rachael’s Caesarian in the cruelest way possible, the joke retina scan, the endless drowning … all of this, it would seem, is part and parcel of a cruel world that (I get it) resembles ours, but one that seems to want its patriarchy cake and, with the spectre of birth on the horizon, present it at the eventual baby shower, too.

Perhaps I’m reading too much into this, but Blade Runner 2049 is nothing is not a text begging to be read. How off-base am I?

L: There’s definitely some weird stuff going on with women in this movie, which is definitely tied into the fertility worship weirdness. It’s probably not a coincidence that two of the female characters very much play into the butch career woman stereotype, and are contrasted with the AI girlfriend, who is able to simultaneously play all the different types of femininity simultaneously, and the sex worker, for whom the domestic AI is almost an addition. It’s a very literal Madonna-whore complex, it seems to me, with the Madonna’s body reduced so far that it is literally spectral.

I don’t know, really, I guess. I think I’ll probably rewatch this in a year or so and have some clearer thoughts on all of what’s going on, mostly just because it’s so much content to ingest.