When James Wan released Insidious in 2010 and the original The Conjuring three years later, it surprised a lot of horror audiences and critics. The director of Saw, and the producer of its string of increasingly grisly sequels, seemed to have taken a sharp right turn, abandoning what fans call “extreme cinema” and detractors dismiss as “torture porn” for haunted-house atmospherics and a more creeping variety of dread.

Reviews

Insiang, Lino Brocka’s celebrated 1976 melodrama of the Manila slums and the first Filipino film to ever screen at Cannes, opens with several ghastly, uninterrupted minutes inside a slaughterhouse.

It’s dirty, bloody, and brutal – pigs, hung upside down, bleed out from hastily punctured throats, before being tossed into vats of boiling water.

The best “mockumentaries” – This Is Spinal Tap, Waiting For Guffman, A Mighty Wind – pull off a neat trick. They tend to endear you to the characters they poke fun at, slyly subverting types and tropes while remaining affectionate in the process.

One of the great curiosities about early horror films, particularly the American variety: why are they so scared of horrifying? Paul Leni’s The Last Warning (1929) – more or less a reboot of his previous The Cat and the Canary from 2 years prior, swapping a spooky old Broadway stage for a spooky old mansion – is typical of this impulse.

Starring the great Louise Brooks, in her final American film before high-tailing it abroad and becoming an icon in G.W. Pabst’s Pandora’s Box (1929), the gritty, tragi-comic hobo yarn Beggars of Life opened the 2016 San Francisco Silent Film Festival last Thursday.

Here’s what transpires in the astonishing first 56 seconds of Ménilmontant, Dimitri Kirsanoff’s 1926 avant-garde masterpiece.

Delicate curtains flutter inside a home’s open window. Suddenly, a woman’s frightened face appears behind them, an assailant trailing. The doorknob turns frantically. The door finally opens and the woman emerges.

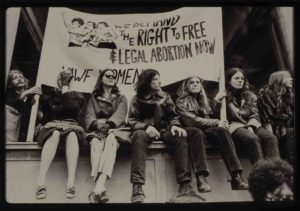

Watching She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry, director Mary Dore’s perfectly agreeable and accomplished 2014 documentary about the birth of the modern women’s movement in the U.S., it’s hard not to feel there’s something staid about the proceedings.

This is less the fault of the film itself than a reflection of how exciting the landscape of documentary film has become in recent years.

This is less the fault of the film itself than a reflection of how exciting the landscape of documentary film has become in recent years.

The Lobster, Greek writer/director Yorgos Lanthimos’ deadpan dystopia and English-language debut, plays its fairy-tale absurdity completely straight, and its weird power accumulates from there.

A plot summary reads as farce, and there are certainly farcical elements. In a world that is recognizably ours and yet exhibits all the trappings of a near-future period piece, or maybe a Wes Anderson whimsy turned poisonous, coupledom is the norm: singles are sequestered into a castle-like hotel and given 45 days to find their mate.

I have now watched M. Night Shyamalan’s The Happening three times in as many days, and it remains entirely perplexing.

I tried several times to conjure up a proper review, but the film itself is so fragmented and bizarre that a standard write-up would fail it.

The Summer of Frozen Fountains is a charming portrait of Tblisi, despite nothing happening

The Georgian film The Summer of Frozen Fountains, director Vano Burduli’s second feature, is a curious beast. It’s light on its feet, dipping in and out of the lives of numerous characters, but seems almost stubborn in its refusal to amount to much.