What is the place of 1997’s Contact in the public consciousness? I’ve never been able to get a solid lock on it. It wasn’t one of the 90s movies that permanently took up residence on basic cable, but it’s a common enough experience that people can make jokes about it.

Other

Richard Linklater has built an entire career as a study in points that do not quite intersect, moments that do not match, but somehow make complete sense placed together.

That’s an impressive feat for a guy who followed up the meandering, anarchic Slacker with the glazed hijinks and pre-collegiate accessibility of Dazed and Confused; the discursive, achingly romantic Before Sunrise (a romance he, with Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke, methodically chips away at in its sequels, constructing the greatest trilogy since Ray’s) with Eric Bogosian’s quasi-punky SubUrbia, followed promptly by a heist film (The Newton Boys).

In real life, I don’t know any criminals of the type depicted in 2012’s Killing Them Softly (or in its source material, the 1974 novel Cogan’s Trade). My high school Bible study leader, a gigantic ex-cop named Al who claimed to be related to “some tough guys” and who always had The Godfather playing when we went to his house, was about as close as I’ve ever gotten.

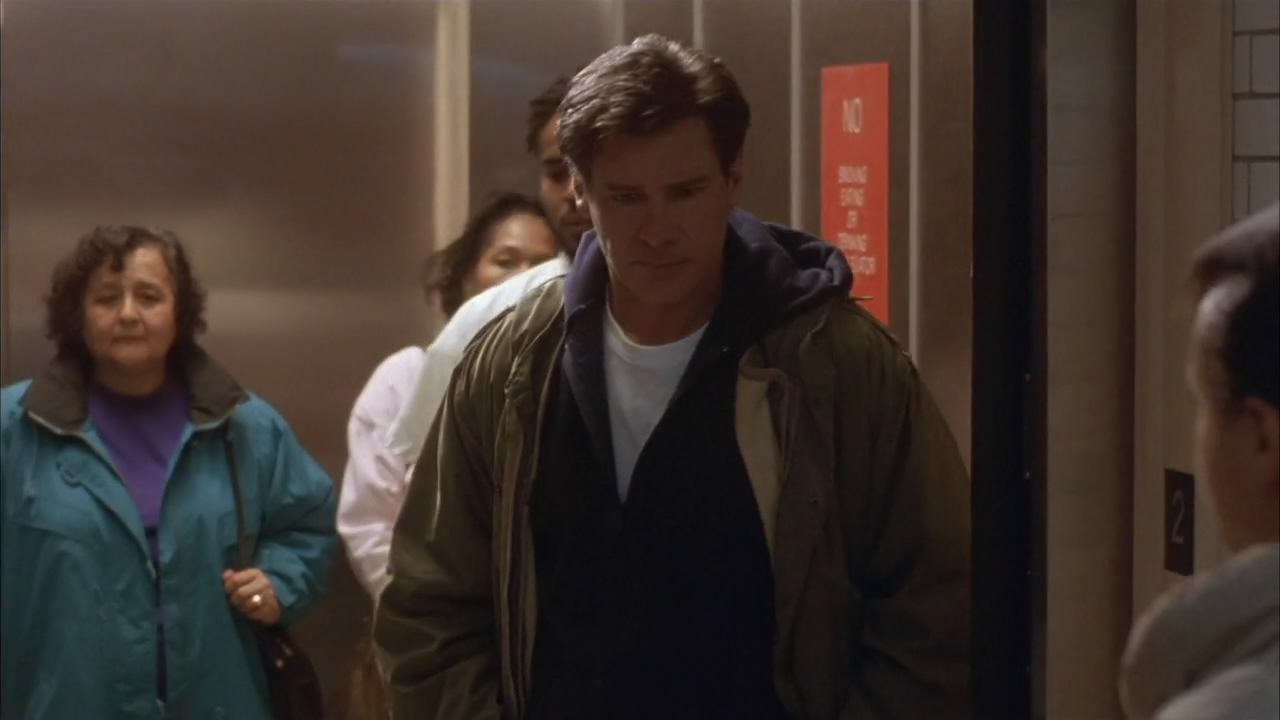

When I joked on social media that The Fugitive is a movie about how easily middle-aged white dudes can get into and out of buildings, my friends mostly laughed. Perhaps because it was presented as a declarative statement, it seems a bit reductive.

Enjoying, enjoy, enjoys; particularly the past tense, enjoyed. The first instinct when leaving a movie theater with someone else: “Well, I really enjoyed that. Did you enjoy it?” Over dinner with friends that night: “Oh, we saw that movie earlier today — we really enjoyed it.”

It is infuriatingly difficult to write about a film you love. I love Bride of Frankenstein.

Trying to locate the source of this affection — to contextualize it in ways that might be interesting and don’t amount to gushing, “Hey, you know what is great?

It’s difficult to base a piece on a Twitter conversation, particularly one you half-remember and which you refuse to look up. I don’t want to look it up because there was nothing particularly unique about this back-and-forth; it’s more useful as an example of a type than as something particularly awful.

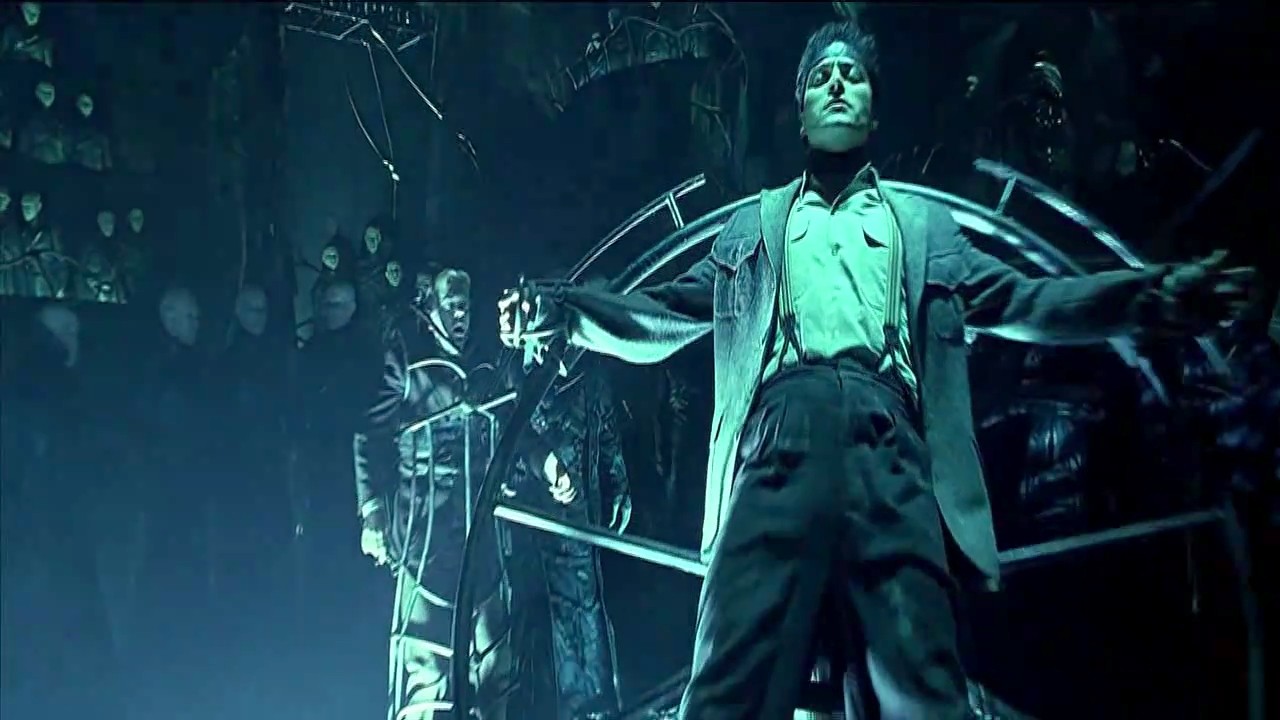

In 1998, two movies were released: The Truman Show and Dark City. Although they both revolved around a protagonist who realizes the city in which he lives is “fake” — an elaborate form of reality television in the former, an alien sociology experiment in the latter — they don’t seem too similar on their own.

The latest offering from genre auteur Jaume Collet-Serra and his hangdog, improbably athletic muse Liam Neeson may not be a great work of art, but, like its predecessors Non-Stop and Unknown, it’s compulsively watchable, even fascinating, and guided by a directorial sense that seems excessive for the material.

In some ways, Jules Dassin’s Night and the City (1950) is an unlikely noir, which (along with an icy reception at the time from critics) might help explain why it’s not the first example of the genre that springs to mind — no femme fatale, no particular mystery, no play-by-play heist gone wrong, a curious fixation on wrestling, of all things.