Boots Riley‘s sense of humor has always tended to the pointedly outlandish, indignant outrage paired with a much goofier sensibility. Case in point: the class-conscious dance track “Five Million Ways To Kill A CEO” from his legendary Oakland hip-hop ensemble The Coup, in which Riley, voice swaggering over the groove, lays out the case against a ruling class who “own sweats shops, pet cops and fields of cola / Murder babies with they molars on the areola,” before suggesting a number of ways to rectify the situation.

Other

There are all sorts of divides between us and the early silent days of Hollywood: assumptions about gender and race; the differences in our ability to fill in what is unsaid (to put back in the implicit sex they had to leave out, for instance); and even the ability to perform the simple act of holding an actor’s face in mind for the seconds until the title card comes up, then retroactively making the face make sense with the words.

Increasingly, our mainstream cinema seems consumed with the act of storytelling itself. We can add American Animals to a list that already includes recent films as different as I, Tonya and Bisbee ‘17. This inward turn is nothing new for the avant-garde and the art-house, long characterized, from Bergman to Godard to Kiarostami, by the foregrounding of artifice.

Calling it “the season’s most huggable film” shortchanges the charm of Hearts Beat Loud, but it’s not entirely wrong.

There are undercurrents of deep melancholy beneath all the indie-rock, Red Hook whimsy that ground it in something real, relatable, and honest.

There are certain rich veins of cinematic tradition that we as film writers find hard to tap into. The perfect filmic tradition for critics is one that has enough coherence that readers are interested in reading new articles about it, but enough uniqueness to each film that we can justify writing about them separately.

As in Steven Soderbergh’s much-loved Ocean’s Eleven, Gary Ross’ Ocean’s 8 begins at a parole hearing for our protagonist. She’s making nice and saying all the right things, arguing for a rehabilitation we genre fans know hasn’t occurred.

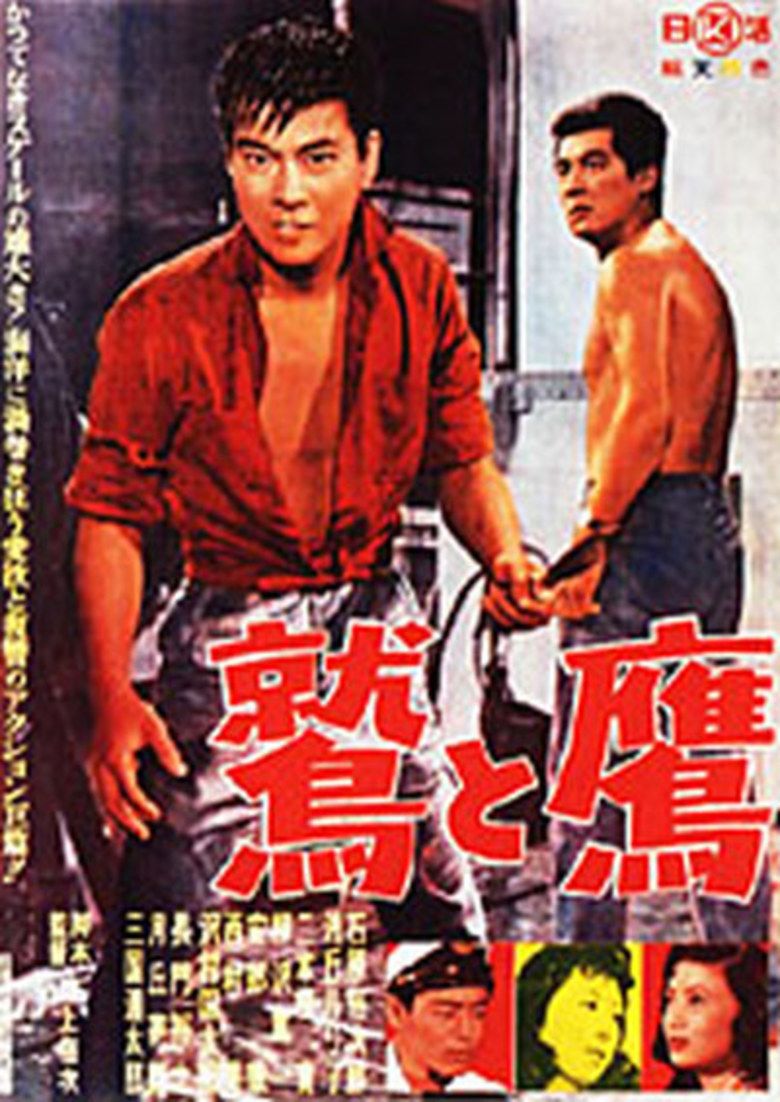

I can’t confirm for sure that the minds behind The Eagle and the Hawk (Washi to Taka, 1957) saw John Ford’s The Long Voyage Home (1940) — a number of shots seem to duplicate ones from the earlier film, although on a ship the number of places from and at which to shoot is certainly delimitable — but I couldn’t stop thinking of the two films next to one another.

Miniatures are inherently unsettling. Like all copies of the world, they carry a whiff of the uncanny, and a possibility that they will escape the control of their creators; in horror movies, we are particularly trained to expect them, infused with some breath of terrible life, to rise up and wreak havoc.

“Tungsten,” you think, occasionally, watching Gilda. “This film that made Rita Hayworth an international sensation, this film that features the most iconic character-introducing shot in all of cinema. It’s about … tungsten.”

Discussions of Gilda (1946) rarely turn on the out-sized role that tungsten — W on the periodic table; atomic number 74; melting point 3422 °C (6192 °F, 3695 K); boiling point 5930 °C (10706 °F, 6203 K), the highest known; density 19.3 times that of water, comparable to that of uranium and gold, and much higher (about 1.7 times) than that of lead — plays.

Late in The Post, we have the scene, mandated by genre, in which Meryl Streep, trying to make the ethically right decision, talks to her daughter about a memory of the daughter’s childhood — the place in which the daughter, who has been vaguely rebellious, tells her to do what she thinks is right.