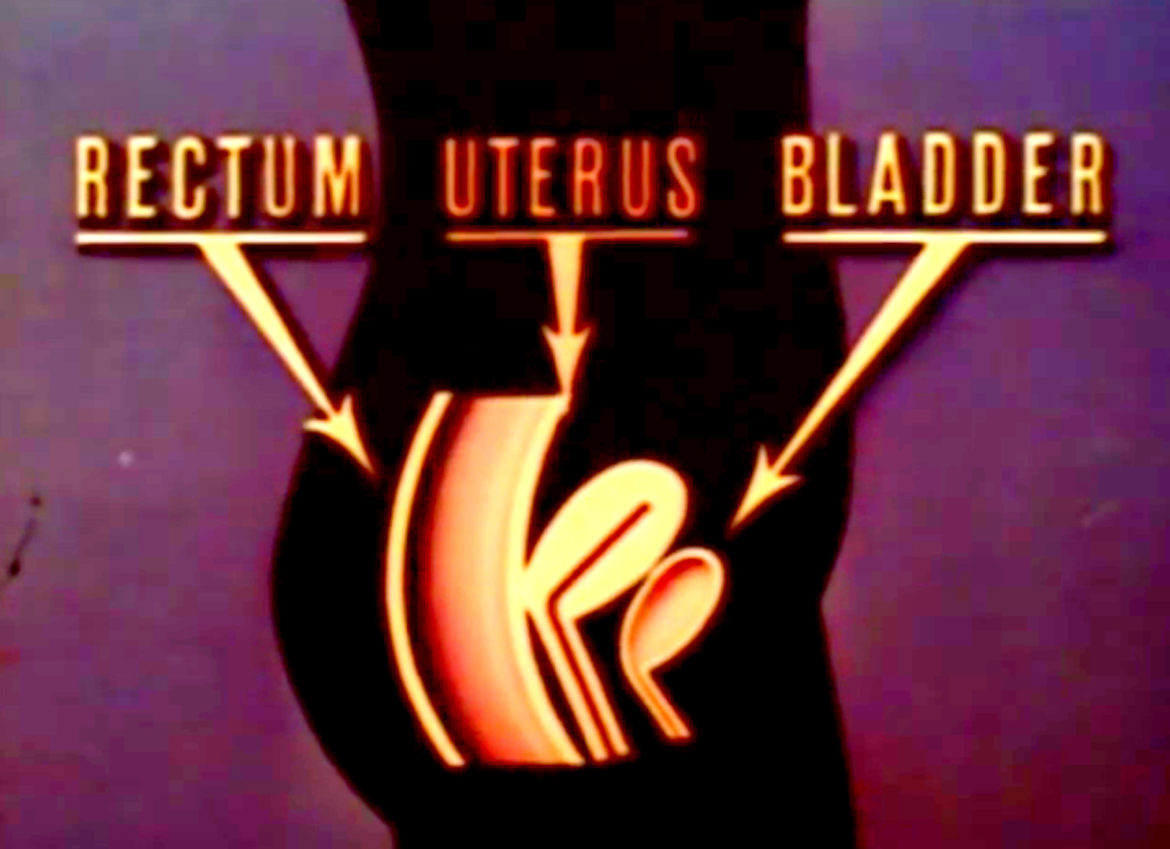

Today, we take a break from esteemed feature films like Scream, Blacula, Scream to look at something even more curious: the once-banned, entirely odd Disney production The Story of Menstruation, a 10-minute animated short from 1946 “presented with the compliments of Kimberly Clark.”

Film

In his A-Z of Horror, Clive Barker includes a section on Black treatments of the familiar horror themes, focusing on Blaxploitation shock features and modern-day horror-core ensembles like The Gravediggaz (featuring Rza from Wu-Tang, under the name The Rza-rector). While there’s an inescapable element of silliness to these efforts (case in point: “Rza-rector”), the main idea – pairing the horror of the Black experience in America to established horror movie themes – has always been a smart one in my opinion.

Straight-ahead comedies aimed at adults occupy a weird space in the cultural landscape. It’s not that they’re invisible exactly – 2014’s 22 Jump Street stands out, and even The Grand Budapest Hotel essentially fits the bill, if mediated through Wes Anderson’s whimsical (and no doubt vintage) Russian nesting doll aesthetic.

Joe Swanberg is still not quite a household name. But with a staggering 27 directing credits to his name, according to IMDB, the mumblecore stalwart can’t be faulted for lack of trying. And things may be shifting. His feature in the first V/H/S was the stand-out, his 2011 starring role in Adam Wingard and Simon Barrett’s terrific suspense flick You’re Next got more attention than usual (editor’s note: see their 2014 Swanberg-less The Guest, one of the best films of the year), and his 2013 Drinking Buddies attractively married the patented low-key approach of his hangout scene to something approximating a Hollywood rom-com.

By all accounts, Vivian Maier was an eccentric and complicated woman, a mystery to those who knew her best (not many) and an outsider artist in the truest sense – a gifted street photographer who hoarded her own work, but continued to snap images everywhere she went in her paid job as a nanny for a series of families.

American Sniper, Clint Eastwood’s latest examination of male violence and its repercussions, is a curious beast. It’s neither as jingoistic as its critics claim (some of whom, embarrassingly, didn’t bother to see the film before reviewing it) nor as nuanced as its defenders submit (see Mark Hughes for a well-done and serious consideration of its merits).

There’s a sense that the phrase “later Godard” – meaning most of the great director’s post-sixties work – is used pejoratively as much as a descriptor: it means impenetrable, pretentious, stridently political, cold, formalism for its own sake.

As I catch up on movies from the last year that I missed in theaters, it’s increasingly clear that all the laments about 2014 being a bad one for film are total nonsense.

The list of excellent movies, or at least the one I’m working on, keeps growing: leaving aside the quiet awards juggernaut of Boyhood (all deserved), that list already includes the tense revelations of Blue Ruin and Calvary, James Gray’s monumental The Immigrant, Paul Thomas Anderson’s Pynchon-noir Inherent Vice … not to mention Ida, Under The Skin, Wetlands, Obvious Child, Noah, and We Are The Best!

David Wnendt’s Wetlands, based on Charlotte Roche’s novel, asks a simple, revealing question of audiences, one that’s never been asked quite so specifically: “How many depictions of anal fissures are you willing to allow in your charming romantic comedy?”

Think hard about this.

I have never seen a full episode of Girls.

I say this at the outset not to demonstrate my hipness or lack thereof, but as a statement of fact that’s relevant here.

Online or in print, virtually all discussions about the work of Lena Dunham – noted screenwriter/director/actress/TV star/author/astronaut (probably) – seem to end up being about Dunham herself.