For all of our cultural emphasis on the lonely, solitary gambler, awaiting one big score or trying to dig himself (it’s always a him) out of a hole of his own making, it’s also true that gambling can create families of sorts by definition.

Commentary

It’s exceedingly easy to dismiss evangelical cinema as an amateurish, maudlin, pandering, and cynical exercise in preaching to the converted. This is at least in part because it’s generally been the case. But the field isn’t completely identical, even if it might look so from the outside: the Left Behind franchise in and of itself demonstrates that there are a number of forms these appeals can take.

The entire filmography of Chantal Akerman is a series of breaths, and No Home Movie is among her breathiest.

This is transparently the kind of eye-rolling claim that makes people tune out — why, after all, should anyone watch or listen to a series of breaths?

There’s a particular type of movie, the kind that depicts bourgeois capitalist decadence and excess, usually in the art world, or more specifically in the film world. La Dolce Vita is the iconic example, and all of the followers reference it; the recent examples I have in mind are The Great Beauty and Knight of Cups.

It’s a sad, cynical day in these United States. With elected officials seemingly hell-bent on depriving people of health care for the worst reasons they can muster, things seem a bit gloomy.

Of course, there is an occasional, fitful awareness that this monstrosity of a bill, which no one voting on has read, can’t make into law in its current form, and that we’re still engaged in the shadow theater of masturbatory spectacle.

When Jonathan Demme died yesterday at the age of 73, the tributes poured out. Not only a prolific and varied filmmaker — a guy who could make an iconic horror movie as easily as the greatest concert film of all time, not to mention studied forays into documentary and slice-of-life realist pictures — but also, by all accounts, a kind, decent human being.

At a crucial moment in Ritwik Ghatak’s Ajantrik (frequently translated as The Pathetic Fallacy), our hero Bimal strokes the most important person in his life and says, “Never mind, Jaggadal. You and I … we’re together.”

It’s a poignant moment, this Bengali portrait of devotion and erotic desire in the face of widespread mockery and community derision.

Faithful readers, as well as people I’ve met casually on the street, probably, will know that I am a huge fan of Nathan Rabin.

I have interviewed him. I have written a tribute to the inherent empathy of his work.

Critical responses to American Honey seem to fall into two camps: those who loved its portrait of outsider culture and female empowerment, and those who felt, in the words of my friend and noted critic Charles Bramesco, that it was”just feral white kids ecstatically and unabashedly screaming the N-word over barely listenable trap-rap.”

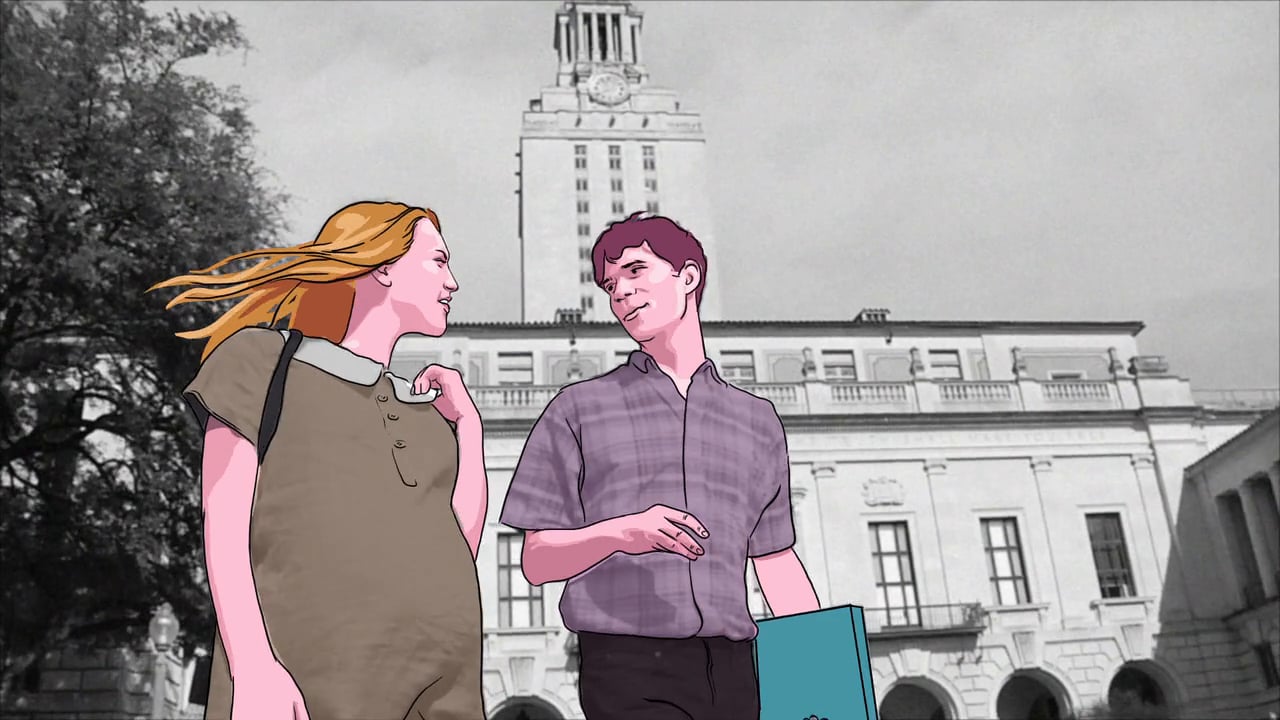

On a blisteringly hot August day in 1966, Charles Whitman — a former Marine who’d killed his wife and mother the night before — climbed the the Main Building tower at the University of Texas with an arsenal of weapons and started shooting.