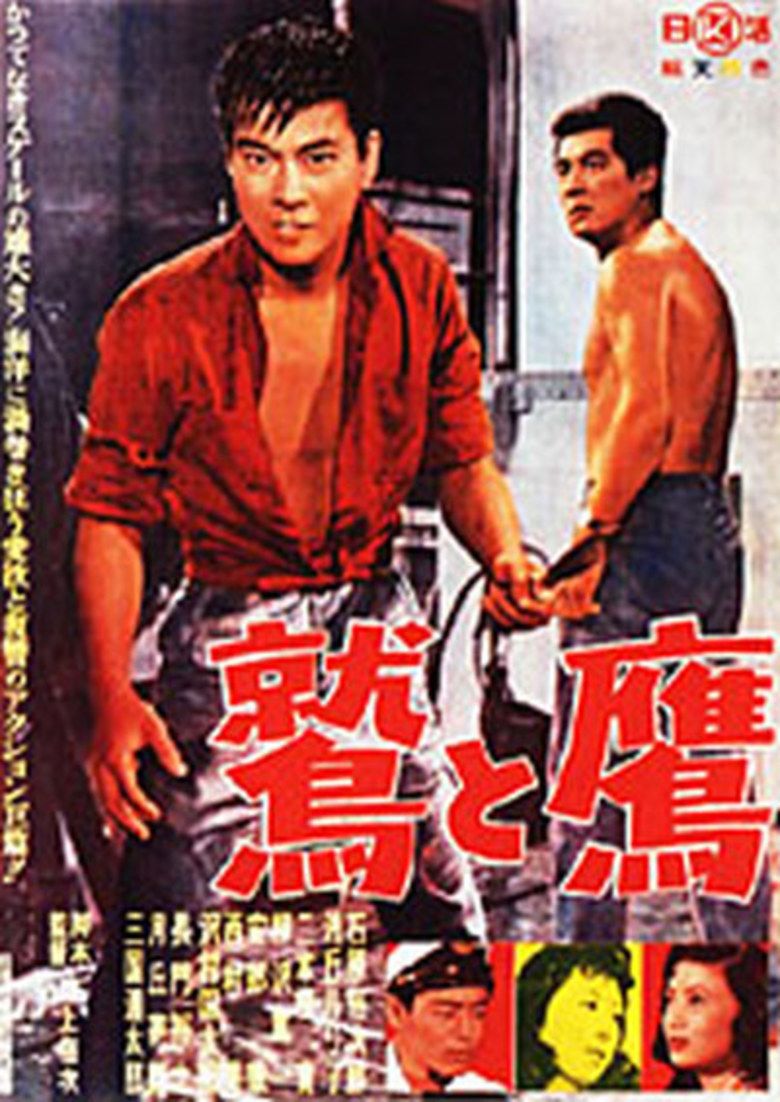

I can’t confirm for sure that the minds behind The Eagle and the Hawk (Washi to Taka, 1957) saw John Ford’s The Long Voyage Home (1940) — a number of shots seem to duplicate ones from the earlier film, although on a ship the number of places from and at which to shoot is certainly delimitable — but I couldn’t stop thinking of the two films next to one another.

Film

Miniatures are inherently unsettling. Like all copies of the world, they carry a whiff of the uncanny, and a possibility that they will escape the control of their creators; in horror movies, we are particularly trained to expect them, infused with some breath of terrible life, to rise up and wreak havoc.

“Tungsten,” you think, occasionally, watching Gilda. “This film that made Rita Hayworth an international sensation, this film that features the most iconic character-introducing shot in all of cinema. It’s about … tungsten.”

Discussions of Gilda (1946) rarely turn on the out-sized role that tungsten — W on the periodic table; atomic number 74; melting point 3422 °C (6192 °F, 3695 K); boiling point 5930 °C (10706 °F, 6203 K), the highest known; density 19.3 times that of water, comparable to that of uranium and gold, and much higher (about 1.7 times) than that of lead — plays.

Late in The Post, we have the scene, mandated by genre, in which Meryl Streep, trying to make the ethically right decision, talks to her daughter about a memory of the daughter’s childhood — the place in which the daughter, who has been vaguely rebellious, tells her to do what she thinks is right.

The city symphony, as a “genre” (can something so short-lived be a genre?), has the misfortune of being mostly associated with a particularly unrepresentative entry: Dziga Vertov’s justly famous The Man with the Movie Camera.

Vertov’s movie is still incredible, and deserves its place in every film history class’ syllabus.

Given that seemingly every day brings with it a new and horrifying perspective on America’s descent into Trumpian doublethink, it can be hard to keep track. It’s not just the outrage cycle, either – we really are living through uniquely dismal times; if the moral affronts aren’t necessarily new, the attitudes towards them, ranging from casual disregard to gleeful celebration, sure seem to be.

We can plot the Great Movies You’re Supposed To Have Seen Canon on a grid, something like the omnipresent Political Compass. One axis is fast vs slow, and the other is positivity-oriented and optimistic vs. mopey depress-os.

A lot of the mutual lack of understanding that sometimes happens when I talk to my fellow film dorks online comes from the oddities of my personal artistic history that have left me to mostly enjoy the slow depress-o corner of the canon map, that corner which has become for many people about as pleasant a place to visit as the dentist’s.

The events of May 1968 exist in memory, of course, but whose memory, and how? The overlapping texts of Philippe Garrel‘s Regular Lovers, Bernardo Bertolucci‘s The Dreamers, and Olivier Assayas’ Après mai offer clues.

Amid all the recollections of ’68 in the past few weeks — whether extolling the energy of a revolutionary moment or gleefully trumpeting its failure, or something in between — I’ve been surprised how many people in my generation, in the U.S.,

In a press conference at the Venice Film Festival, Philippe Garrel once remarked, “Given that nowadays in France, there is a tendency to forget 1968, to erase it from the map of history, I thought it would be useful to raise the question ‘what is cinema for?’

If Monty Python’s “Summarize Proust Competition” had been real, it would be a cakewalk (“A man reminisces a lot, goes to a party, and decides to write the book you’re reading”). A far harder version would take aim at a much shorter book: Chandler’s The Big Sleep.